From the syllabus for Religion and Ethics (Paper 2):

4.1 Meta-Ethics

- Cognitive and non-cognitive uses of language, realism and anti-realism, language as factual or symbolic, the nature of ethical assertions as absolutist or relative, ethical naturalism, the naturalistic fallacy, the is–ought gap, the problem of the open question, ethical non-naturalism, intuitionism, prescriptivism.

- b) Emotivism, the influence of the logical positivism on emotivist theories of ethics, ethical language as functional and persuasive. Developments of the emotivist approach and criticism of it.

With reference to the ideas of G E Moore and A J Ayer.

Evaluate which meta-ethical theory is most useful in determining the meaning of ethical language.

NOTE: there is no way that all the information below could be included in response to a question of this type in an examination setting, as there simply isn’t the time to write this much. However, a decent answer should include some of what can be found below, strike a balance between the realist/cognitivist and anti-realist/non-cognitivist camps, and reference the thinking of GE Moore and AJ Ayer.

Meta-ethics is the study of the meaning and purpose of ethical language: what do we mean when we use words like ‘good’ and ‘bad’, ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ in moral statements? And what do we hope to achieve when we make such statements?

Meta-ethical theorists can broadly be assigned to one of two camps on this issue: on the one hand, there are the realists or cognitivists. According to these philosophers, there are objective moral facts to be known about morality in the same way that there are scientific facts to be discovered about the world.

In other words, if someone were to invent the moral equivalent of a metal detector, a ‘good/bad’ detector, moral realists are committed to the claim that this machine, when pointed in the direction of, say, someone lying to a would–be murderer (to use Kant’s famous example), really would work. Something would register on its instruments, like the badness of telling a lie, in the same way that a beachcomber, with the assistance of a metal detector, might be dismayed to find it registering a crushed can of Coca-Cola, rather than a valuable Roman coin, hidden beneath the sand.

Supporters of this view vary in the manner according to which these moral facts are to be detected. For example, from a normative point of view maintained by, say, Kant, they are to be discovered entirely through rational analysis and the application of the various formulations of his categorical imperative. Alternatively, subscribers to Divine Command Ethics might say they can be found in a sacred text and are supplied by God, while followers of Natural Law theory are encouraged to discover and act upon their God-given natural inclinations.

For all the members of this camp, moral knowledge is cognitive: there is something to be known (or cognized) which is either true or false, in the same way that it would be true to state that water freezes at zero degrees temperature, but false to say that freezes at fifty degrees centigrade.

One popular cognitivist/realist view of ethical language is represented by Ethical naturalism. According to this view, ethical statements can be verified or falsified by evidence. If we want, for example, to establish that Nazism was bad, we will find overwhelming evidence of this in the historical records.

For GE Moore though, terms like ‘goodness’ are, like the word ‘yellow’, indefinable. He tried to show this by deploying something called the Open Question argument. Take any suggested definition of ‘good’. It does not matter which one we choose. Examples might be ‘that which gives pleasure to the most people’, or ‘that which is commanded by God’. Let us call these defining phrases ‘C’. If the definition was successful, the question ‘Are things which are ‘C’ good?’ would be a closed question, because the answer would obviously be ‘yes’. But in fact, whenever questions like this get asked, they are ‘open’ in the sense of being open to debate because people argue about them. It follows that no definition of ‘good’ is successful.

Moore also felt that ethical statements remain vulnerable to the naturalistic fallacy, as they are neither self-evidently true or verifiably true. For example, the statement ‘adultery is wrong’ is not like an analytic statement, such as ‘a bachelor is an unmarried male’. We discover this when we invert it. An analytic statement, when inverted, inevitably involves a contradiction. To say that ‘a bachelor is not an unmarried male’ is contradictory. But to claim that ‘adultery is not wrong’ is not. So moral statements cannot be analytic.

Can they be synthetic, capable of being true or false, as ethical naturalists claim? Again, the answer is no. The naturalistic fallacy is famous in philosophy for illustrating the gap that exists between an ‘Is’, a statement of fact, and an ‘Ought’, a statement with moral content. For example, it is well known that many people commit adultery. But no matter how many genuine cases of adultery we might encounter, none of them will reveal whether people who commit adultery ought not to.

The last two paragraphs also form the basis for AJ Ayer’s analysis of the meaning of ethical language, a point which we shall return to shortly. For the moment it remains to sketch in the final details of Moore’s position.

Surprisingly, Moore remains in the realist camp when it comes to ethical language, in spite of his scepticism. He still thought that there were objective moral truths that are independent of human beings. However, these truths can only be known intuitively, the reason for this being that we are all, he felt, naturally equipped to recognise goodness whenever we encounter it.

Unfortunately, there are numerous problems with Moore’s theory. It may be deemed useful in one sense, as it captures the experience all of us sometimes have of instantly knowing that something is wrong without having to reflect on the matter. However, that spontaneous response may itself be based on a lot of previous experience that was not gained through intuition. We might, for example, intuit that what the Nazis did was wrong because of our continual exposure to this point through the medium of things like history books, novels, movies, documentaries and so on. So when we encounter similar behaviour to that perpetrated by the Nazis, we automatically condemn it, rather in the manner that a driver performs gear and steering movements instinctively, after having spent sufficient time beforehand learning to drive. Our past experience of Nazism would therefore have been gained through familiarising ourselves with the facts, proceeding in a manner that conforms to the process outlined by the ethical naturalists that Moore criticises. Another intuitionist, HA Prichard, thought that a reasoning process based on the facts of a situation took place prior to intuition showing which particular action was right. Prichard’s account of intuitionism therefore does not seem vulnerable to this criticism.

Moore’s theorising also seems to avoid the issue of how children could possibly get to know moral truths intuitively, in the complete absence of any methods and clues. Furthermore, according to the philosopher John Doris, psychologists have investigated moral intuitions, and found that they vary according to both socioeconomic status and ethnic background. Such variations should not be possible if Moore is correct, and also undermine Ross’s attempt to identify universal prima facie duties that can be ascertained through intuition.

Finally, Moore seems to assume that words like ‘good’ or ‘yellow’ are indefinable. Perhaps they are, but maybe a precise definition exists but has yet to be identified. In which case, moral statements would need to be re-classified as closed.

Both of the above criticisms also apply to Prichard.

Given then, that cognitivist meta-ethical theories remain unconvincing, what does the other camp have to offer?

First of all, if we abandon the view that ethical language is capable of being true or false, we are then committed to the view that it must be non-cognitive and anti-realist in nature. In other words, there is nothing for our aforementioned good/bad detector to detect because there are no moral facts out there waiting to be discovered. So instead, words like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ must serve a different purpose in ethical statements. What could that purpose be?

For Emotivists like Ayer, moral statements cannot be verified either self-evidently through logic, or through observation, as we saw earlier. Instead, they are expressions of subjective opinion based on emotion. Ayer is famous for his ‘Boo-Hurrah’ theory, according to which if someone says that murder is wrong, they are, in effect, simply saying ‘Boo to murder’, and by implication ‘Hurrah to not killing people’. Words like ‘good’ and ‘bad’ therefore refer to feelings rather than facts when employed in moral statements, and the purpose of such statements is to arouse similar feelings on others.

Ayer’s theory does seem to be useful as it accounts for the passionate emotions that moral issues like abortion and euthanasia inspire in people. But Ayer seems to have neglected the element of persuasiveness that a later Emotivist, CL Stevenson, regarded as an additional feature when it comes to the content of moral language and the intent of the speaker.

However, Emotivism suffers from one of the problems encountered with ethical relativism, namely, that everyone’s opinion is equally valid. And so however much it seems to work as an analysis of moral language, at the normative level of ethical debate it seems insufficient and not especially useful when it comes to deciding whether those on the ‘Boo’ side of the debate deserve our support rather than the ‘Hurrah’ advocates.

Emotivism also has a hard time explaining why we admit to the possibility of error in moral judgements, as this is a possibility that does not actually seem to exist if moral judgements are incapable of being true or false.

A last non-cognitivist theory is that proposed by Hare: prescriptivism. According to Hare, when we use moral language in everyday speech, we are acting a bit like a doctor writing a prescription for a sick patient, in the sense that our conversation tends to include lots of ‘oughts’ and ‘shoulds’, just as a doctor might advise us to drink less alcohol or to take a certain type of medicine.

In his 1952 book The Language of Morals, Hare suggested that a statement could only claim to be moral when it called for an action which was universalisable (that is, when the person uttering the proposition saw it as equally appropriate both to himself and to all others). Thus, for example, the proposition “All Jews should be killed” could only be regarded as fulfilling the requirements of a ‘moral’ proposition if the person saying it was willing, if he found himself to be a Jew, to be killed. In other words, whatever advice we prescribe should take account of all those affected by that advice.

In the same interview, Hare discussed the examples of the Vietnam War and World War Two. Hare thought that the terrible suffering brought about by America was immoral and should not have been prescribed [although Hare does not mention this, he may have been thinking of the consequences of the use of napalm]. However, Hare thought that the consequences for the German people of Britain not entering the war would have been worse than if we had. So the prescription here was morally sound, even when we put ourselves in the position of being German and therefore potentially on the receiving end of Allied bombing.

Prescriptivism may seem like a useful theory, both in terms of its analysis of moral language and its practical applications. However, it too suffers from some serious problems.

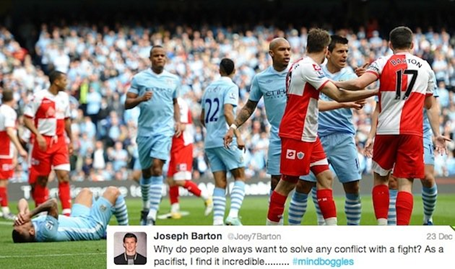

First of all, Hare insists on consistency between thought and action. If someone fails to act on their own prescriptions then he does not think that the language they used to formulate the prescription can be considered moral language in the first place. A good example would be former premiership footballer turned manager of Bristol Rovers FC (at the time when this page was last edited) Joey Barton, who not long before being sent off for violently attacking opposition players in a crucial end-of-season match, declared himself to be a pacifist on Twitter.

However, all of us fall short of our own moral prescriptions from time to time (e.g. to be nicer to our parents, to behave as a suitable sixth-form role model) or fail to live up to them without being hypocritically insincere. For example, we might simply be distracted by an overwhelming personal issue, or be suffering from a bout of depression that deprives us of our usual motivation to do what we know we should. In these circumstances, it seems unreasonable for Hare to insist that our language is not truly moral.

Also, it seems possible to believe in fanatical prescriptions without them seeming to break Hare’s rules about universalizability and commitment. A Stalinist, for example, might think that in order to bring about a truly communist society, there may have to be innocent casualties of the revolution. They might even regard the sacrifice of their own life to be necessary for this greater cause.

Having surveyed the territory, what conclusions might we reach about the usefulness of the various meta-ethical theories when it comes to our understanding of moral language?

First of all, the ancient and famous Buddhist parable of the blind scholars and the elephant might be helpful here. Since the blind scholars did not know what the elephant looked like, each of them formed a very different mental picture of the animal through touch. For example, the scholar who examined the trunk gained a very different impression from the man who explored the sharp tusks, with none of them finally gaining a comprehensively accurate picture.

One might, through analogy, therefore suggest that ethical naturalists correctly emphasise that moral deliberations must take the facts of a situation into account, with the intuitionists highlighting the often spontaneous manner through which we ‘just know’ what the right thing to do is. GE Moore has also usefully demonstrated how the terminology of ethics defies attempts to pin it down, while Ayer, Stevenson and Hare each draw our attention to the emotional, persuasive and prescriptive elements that all emerge from a linguistic analysis of moral language. And yet, at the end of the day, one senses that there is something unsatisfactory about all meta-ethical theorising. Why is this?

First of all, it could be said that many of the findings of meta-ethical enquiry are so obvious that it hardly takes much philosophising to uncover them. For example, it does not take a lot of effort to notice that people often get worked up about moral issues (Ayer), try to get others to agree with them (Stevenson) or find themselves dispensing advice (Hare). Moreover, when making moral decisions, the facts of the matter usually have a part to play (naturalism), though people often go with their first impressions or ‘gut feelings’ (intuitionism).

Overall then, it may not seem unreasonable to suggest that the whole enterprise of meta-ethics seems to be fairly useless if its ‘discoveries’ are so self-evident.

Secondly, meta-ethics as a discipline could also be criticised for reducing moral debate to a form of mere linguistic analysis and might even be seen as offensive. For example, it is doubtful that survivors of Auschwitz or the victims of Islamic terrorism would be impressed with Ayer’s view that their beliefs amount to no more than an emotive ‘Boo to fascism’ or ‘Boo to al-Qaeda’.

In conclusion, I would therefore argue that for meta-ethics to have any value at all, it cannot be ring-fenced and seen as a topic devoted exclusively to determining the meaning of moral language, as something separate from normative ethics. To remain in any way useful, it should keep in mind at all times, the much more important business of finding out why human beings sometimes do terrible things to each other and how this might be prevented.

More on the Naturalistic fallacy

If it is correct, the Naturalistic Fallacy spells trouble for the main normative ethical theories. For example, from the fact that humans tend to seek pleasure and avoid pain it could not then be said that mankind ought to aim collectively at the maximization of happiness (Utilitarianism). Or from the fact that humans are capable of rational, autonomous action, it cannot be then be said that these qualities ought to be used to make moral decisions (Kantian ethics). From the fact that we naturally seek to procreate, preserve life etc. it could not be said that we ought to do so (Natural Law). Finally, from the fact that certain people are virtuous it cannot be claimed that everyone should aim to be virtuous (Virtue Ethics).