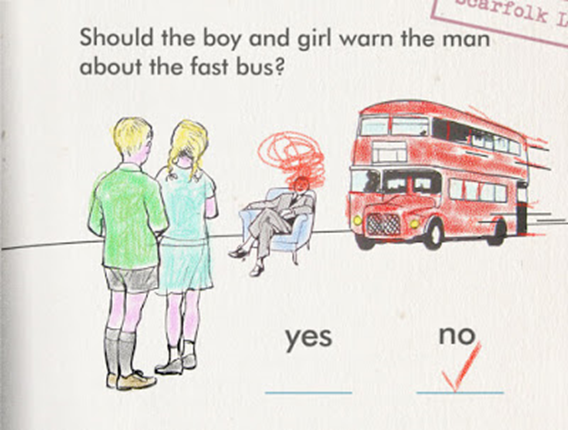

We begin by looking at a famous thought experiment that is often used to introduce this topic: the Trolley Car dilemma.

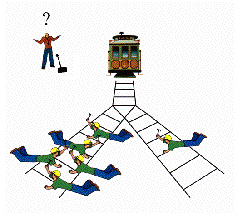

Trolley Car Dilemma Version 1

You are walking near a trolley-car track when you notice five people tied to it in a row. The next instant, you see a trolley hurtling toward them, out of control. A signal lever is within your reach; if you pull it, you can divert the runaway trolley down a side track, saving the five — but killing another person, who is tied to that spur. What do you do? Most people say they would pull the lever: Better that one person should die instead of five.

Trolley Car Dilemma Version 2

Now, a different situation. You are on a footbridge overlooking the track, where five people are tied down and the trolley is rushing toward them. There is no spur this time, but near you on the bridge is a large man. If you heave him over the side, he will fall on the track and his bulk will stop the trolley. He will die in the process. What do you do? (We presume your own body is too light to stop the trolley, should you be considering noble self-sacrifice.)

Moral theories fall into several categories. There are those that are ABSOLUTE and those that are RELATIVE. There are those that are DEONTOLOGICAL and those that are TELEOLOGICAL or CONSEQUENTIAL, those that can be said to be OBJECTIVE and those which are thought to be SUBJECTIVE.

What does the Trolley Car Problem show?

First of all, it helps us to understand what morality is.

Ethics/Morality – this is the branch of philosophy concerned with ideas and theories about what is right and wrong and good and bad behaviour.

Philosophers have generally approached morality in two different ways.

- Only the consequences matter. So when people have to choose between different options when making a moral decision, they should decide on the option that they think will have the best consequences for themselves and everyone affected by it. People who think like this are called Consequentialists. They start by asking themselves ‘Which choice will have the best effects and produce the best outcome for everyone affected by this situation?’

In the case of the first version of the Trolley car problem, people who decide to pull the lever are thinking consequentially about the situation. Pulling the lever will have the best consequences because only one person is killed instead of five.

Just to complicate things a bit, the word ‘teleological’ (from the Greek word ‘telos’ meaning ‘goal directed’) is also used to describe ethical theories that focus on outcomes or consequences.

2. Morality is a set of rules or duties that people need to be follow so that they can then apply them to any given situation e.g. ‘Thou shalt not kill’, ‘Honesty is the best policy’. So the consequences of our actions never matter. They are irrelevant because certain things are just wrong. People who think like this are called Deontologists (from the Greek word deon meaning ‘duty’). The most extreme version of the deontological approach to ethics is one which says that there can never be exceptions to these rules e.g. you would still have to tell the truth to an angry, would-be murderer if they knocked at your door holding a knife and asked where your best friend is, and the friend was hiding in your bedroom. So the first thing a deontologist usually does is to ask themselves ‘What rule should I follow in this situation?’ or ‘What is my duty?’ In the case of the second version of the Trolley Car Problem, people who think that it is wrong to push the large man onto the track are thinking deontologically. They could be said to be following this rule: ‘It is wrong to kill an innocent human being.’

In summary, moral theories fall into several categories. There are those that are ABSOLUTE and those that are RELATIVE. There are those that are DEONTOLOGICAL and those that are TELEOLOGICAL or CONSEQUENTIAL, those that can be said to be OBJECTIVE and those which are thought to be SUBJECTIVE. Let’s now review and explore these approaches in more detail.

ABSOLUTISM

Absolutist approaches are ones where an ethical rule is true and applies in all situations. It doesn’t depend on culture or time or race or circumstances.

Supporters of Divine Command Ethics hold this view. God is the one who tells us what is right and wrong. So followers of DCE (Divine Command Ethics) do not have to think too much about ethics, because there is an authoritative set of instructions, a handbook of how to live to be found in the relevant sacred text e.g. the Bible, the Qur’an.

The 10 Commandments are examples of absolute rules that religious people claim have their authority in God.

Such absolute rules are DEONTOLOGICAL. i.e actions or rules that are inherently right (or wrong).

Kantian ethics is also Deontological and Absolutist, but is based on reason. Once a moral rule or maxim has been shown to be rational and capable of being acted on, it should be followed in all situations e.g. the duty to tell the truth holds even in the case of the famous example of the would-be murderer.

An OBJECTIVE ethical theory is one which maintains that there are moral facts, in the same way that there are facts about the stars and planets. An ethical theory called Natural Law theory works like this because it is based on the idea that we can work out what to do from looking at how God has designed us and the world e.g. we seem to have been designed to procreate, therefore that is something we should do. Very recently, the philosopher Sam Harris has argued that we can use science to help us decide what is right and wrong. In particular, he has suggested that we can use neuroscience to identify which societies promote behaviour that leads to human well-being. This is because brain scans of happy, well-adjusted people look different from those that aren’t. Harris is very critical of ethical relativism and thinks that his method will help us to OBJECTIVELY prove which ethical theories really work. On this basis, it could, for example, be predicted that the brains of members of the Taliban will show more activity in areas of the brain that are active when we are angry or afraid (because the Taliban tend to be intolerant and are afraid of Allah’s judgement). For this reason, Harris does not agree with Hume’s view (see below) that we can never work out what we ought or should do from the facts of human existence.

RELATIVISM

For ethical relativists, morality is relative to specific times, places and situations. So right and wrong is usually decided by working out which action will have the best consequences relative to the situation at hand. Nothing is decided in advance. This approach has a long history too. Protagoras (Greek 5th century BC) said nothing was absolutely good or bad. It depended on your own personal viewpoint.

David Hume – argued that morality was more of an expression of sentiment (emotion/feeling) rather than fact.

Liberal, Western, non-religious views tend to be more relative, and can clash with absolutist viewpoints e.g. Muslim leaders, for example, who insist on a certain standard of dress for women as described in the Qur’an.

The theory of ethical relativism can be stated as follows:

- Different cultures have different moral codes.

- Therefore there is no objective truth in morality. Right and wrong are only matters of opinion, and opinions vary from culture to culture.

There are types of relativism:

CULTURAL Relativism – where an action is right or wrong relative to a particular culture e.g. the Japanese practice of eating an endangered species – the whale.

SUBJECTIVE relativism – this is where the individual decides for themselves what their standards of right and wrong are going to be e.g. atheistic existentialism – a philosophical movement which argues that we are in this position anyway because there is no God and no obvious meaning to human existence. But this situation means that we are free to define our own moral values.

Utilitarianism and Situation ethics are examples of relativist theories. Existentialism is an example of an ethical theory that involves subjective relativism in moral decision-making.

STRENGTHS OF AN ABSOLUTIST APPROACH

- An Absolutist approach to morality is arguably strong because it is clear and provides a universal code to measure things against e.g. The UN Declaration of Human Rights was written in an absolutist way.

- If Harris’s argument is valid, then an ABSOLUTIST, DEONTOLOGICAL and OBJECTIVE form of ethics may find support in science. And it could also be flexible: there may be more than one approach to morality that could be scientifically proven to result in human well-being.

- It could be argued that some moral values are universal, even though different societies seem to exhibit different forms of moral behaviour. For example, even though Eskimos have been observed to practice female infanticide, this is not because they do not value the lives of their children. It is because a lot of male Eskimos die hunting for food, so that this type of infanticide maintains a balance between Eskimo men and women in the population of their society.

- It could further be argued that Absolutist theories acknowledge a simple truth that there must be some moral rules that all societies have in common (e.g. against lying and murder), because those rules are necessary for any society to exist in the first place. For example, the Greek historian Herodotus (from the 5th Century BC) noted that while the Greeks cremate the corpses of their fathers, an Indian tribe known as the Callatians eat the dead bodies of their parents, with both groups expressing horror when informed what the other lot did. Now it might be possible to use this example as supporting evidence for ethical relativism. However, an Absolutist could reply that in each tribe, some notion of honouring the dead is at work, and that Absolutists are in a better position to identify what that notion should be.

- An Absolutist approach ensures that moral decision making is consistent.

WEAKNESSES OF AN ABSOLUTIST APPROACH

- It doesn’t allow for changing cultures or circumstances, or individual attitudes and ideas. It does not allow for exceptions to be made to moral rules e.g. Kant’s rule about lying to a would-be murderer.

- Some absolute morals contained in sacred texts seem out of date e.g. the Bible’s intolerance of homosexuality.

- Exodus 22v18 ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’ helped to burn alive tens or hundreds of thousands of women in Europe and America in the Middle Ages. Surely this proves that terrible consequences result from following absolute rules.

- Rules are not concerned with the outcomes of an action. But as most people would probably agree that the consequences of not lying to a would-be murderer would be bad, perhaps it is a good idea to consider outcomes.

- David Hume argued that ethical statements cannot be derived from factual states of affairs. In other words, there are no facts that make ethical theories true. For example, we might be able to establish how many people in a community had sex before they got married but this data will not reveal to us whether people ought or ought not to have sex before they are married (though note that Sam Harris has recently challenged this view – see above – and it could be argued that we should not expect the process of deciding standards of right and wrong to give us results that are as definite as, say, those arrived at through scientific or mathematical research ).

- It could be argued the followers of God-given moral rules have decided in advance what they think the moral rules should be and then cherry-pick passages in a sacred text that seem to give support to their opinion. So they are not really genuine Absolutists and are simply pretending to look at morality this way so that they can force their views on other people and make them look as if God is on their side.

STRENGTHS OF A RELATIVIST APPROACH

- It encourages the toleration of different ways of living.

- It is flexible and takes account of specific situations e.g. ethical relativists would not be concerned about lying to a would-be murderer about where a friend is (unlike Kant). In other words, exceptions to moral rules are tolerated because CONSEQUENCES are considered.

- It allows people to take responsibility for their actions because they don’t need to blindly follow absolute, deontological rules (as in Divine Command Ethics)

- An awareness that morality is relative to a culture, time or place helps us to identify and challenge teachings that are out of date or reflect a tradition that may have gone on for generations but should be challenged e.g. female genital mutilation in parts of Africa.

WEAKNESSES OF A RELATIVIST APPROACH

- Many people are worried that as religious belief loses its grip (and Absolutist ethical teachings are no longer supported), that people’s behaviour will get worse and we will end up with an ‘I make my own rules’ form of morality (subjective relativism) in which anything goes and people no longer take responsibility for their behaviour.

- A famous quotation apparently falsely attributed to the Russian novelist Dostoevsky states that, ‘If God is dead [i.e. if belief in God is dying out], everything is permitted’. When faced with an argument for a godless world, it often gets mentioned by religious believers, who insist that faith in God also provides a bedrock, a secure foundation for moral values. Perhaps they have a point : without a moral lawgiver, how can there be a moral law?

- Relativism does not allow a society to progress and improve because present practices cannot be criticised if there is no OBJECTIVE standard to compare them to.

- If relativism is true and morality is a matter of opinion, then there is more than one set of moral principles, and none of them can be said to be objectively superior to any other. In which case, it makes no sense to talk about some moral values being better or worse than any other. But morality is not possible if we are unable to make judgements like this. Therefore, is relativism is true, it could be said to make morality impossible.

BUT: this previous point could itself be questioned. Moral philosophy is arguably all about being able to come up with the best reasons for the opinions and ideas we hold. So, for example, if we want to criticise rather than tolerate a practice which we morally disapprove of in another culture – for example, the denial of education and other rights to women by the Taliban, or the eating of whale meat by the Japanese – then it is up to us to defend our point of view with better reasons than the Japanese can produce to support their position on an issue like this.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning 3 other terms.

- Descriptive Ethics – this is simply about describing and comparing different kinds of moral beliefs and behaviour e.g. giving an account of the beliefs and practices of African tribes for whom female genital mutilation is considered to be moral. A descriptive ethical question might be, ‘What do Sri Lankan Buddhists think about sex before marriage?’ Another might be, ‘Are these beliefs the same as those held by Japanese Zen Buddhists?’

- Meta – Ethics – this is all about the study of ethical language. What do we actually mean when we use words like ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, ‘ought’ and ‘should’? When we make moral statements, are we just saying how we think and feel about a moral issue? Or is ethics more than just a matter of opinion? Are there ethical facts to be discovered about life in the same way that there are scientific facts to be discovered?

- Normative Ethics – this is the type of ethics which tries to establish what is right and what is wrong by proposing systems for working this out. Utilitarianism, Situation Ethics and Kantian Ethics are all examples of normative ethical theories.