This blog entry is a one of several that are of relevance to the OCR syllabus for Business Ethics. The site itself is structured around the current Edexcel course. Business Ethics does not feature on that course. However, an attempt has been made here to ‘kill two birds with one stone’, insofar as some of the content below overlaps with the Edexcel specification as far Environmental Ethics and Religion and Equality are concerned and duplicates some of the information that can already be found on those topics on this site.

Please note that the first half of this lengthy post does no more than create a very necessary backdrop for a consideration of issues that are mentioned in the OCR syllabus. This is because it is simply not possible to arrive at any kind of informed judgement about whether human beings can flourish in the context of capitalism and consumerism, as well as the impact of globalisation, without knowing quite a bit about capitalism, and especially its neoliberal variant, to begin with. In undertaking such a task it is also important to look at at least one alternative to capitalism that may be better equipped to produce the same effect. So this is why Marxism gets mentioned.

With respect to the notion of ‘flourishing’, consideration is also given to a topic which has hitherto received little attention, namely, an assessment of the effects of the introduction of free market capitalist policies into state and higher education over the last thirty five years, both here and in the USA. Hopefully, a description of the responses of four philosophers of significance, Mary Warnock, Mark Fisher, Martha Nussbaum and Michael Sandel, will demonstrate that this is a story that is very much worth telling.

Lastly, because some OCR talking points overlap with each other, the same information is repeated in different sections of this blog entry in a few instances.

The current OCR syllabus for Business Ethics includes the following Key Ideas:

Corporate social responsibility – what it is (that a business has responsibility towards the community and environment) and its application to stakeholders, such as employees, customers, the local community, the country as whole and governments.

Whistle-blowing – what it is (that an employee discloses wrongdoing to the employer or the public) and its application to the contract between employee and employer.

Good ethics is good business – what it is (that good business decisions are good ethical decisions) and its application to shareholders and profit-making.

Globalisation – what it is (that around the world economies, industries, markets, cultures and policy-making is integrated) and its impact on stakeholders.

Learners should have the opportunity to discuss issues raised by these areas of business

ethics, including:

• the application of Kantian ethics and utilitarianism to business ethics.

• whether or not the concept of corporate social responsibility is nothing more than ‘hypocritical window-dressing’ covering the greed of a business intent on making profits.

• whether or not human beings can flourish in the context of capitalism and consumerism.

• whether globalisation encourages or discourages the pursuit of good ethics as the foundation of good business.

WHAT IS CAPITALISM?

Capitalism is a theory which maintains that the best economic system is one where the means of production (factories, machinery and so on) and distribution are owned primarily by private individuals and corporations. The prices of labour and goods are determined by the free market and not by central government. Profits are claimed by individual company owners or, in the case of corporations, by shareholders. The origins of this theory can be traced back to the writings of the Scottish enlightenment philosopher Adam Smith.

In The Wealth of Nations, Smith sketched out his vision of a society based on free-market competition, according to which, a more prosperous society is one in where people are allowed to indulge their essentially selfish desires in the marketplace. So, for example, a seller wishes to maximise profit, while a buyer wants the best deal on offer. Meanwhile, those who produce goods or services for the seller, his or her employees, would want as high a wage as possible, while their employer would again wish to keep wages as low as possible to maximise profit.

For Smith, provided there is competition (created by the possibility of other sellers stepping in to offer the same product for a different price, or conversely for a potential employee to offer their services for a lower wage), a natural equilibrium will result from the outcome of many thousands of decisions that are made in this manner, provided that there is no outside interference and the market remains free. What Smith referred to as an ‘invisible hand’ takes care of all this, and the only business of government is to prevent monopolies from being created, and any ‘price-gouging’ that results from suppliers conspiring together to fix their prices at similar, artificially high levels.

Capitalism tends to therefore be inevitably accompanied by consumerism – a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts – which in turn requires continuous economic growth.

Although the economic landscape has changed beyond all recognition since the time of Smith, it is fair to say that over the last forty years or so, free-market capitalism has assumed a more radical form (commonly referred to as ‘neolliberalism’) and become the pre-eminent economic theory in the world, as articulated by Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman (among others), and represented by the policies of Thatcherism, so-called ‘Reaganomics’, Bill Clinton’s market globalism, Tony Blair’s Third Way, and what might be referred to as Trussonomics.

NEOLIBERALISM

Although it would be incorrect to describe Adam Smith as a neoliberal, neoliberals put his ideas about the free market at the heart of their philosophy but go on to make some very big claims about the benefits of a free market system. Their basic idea is that free market exchange can form the basis for an entire ethic, one which is capable of acting as a guide for all human action. In other words, they believe in the power of self-regulating free markets to create a better world. One example of this is that allowing for free trade on a global scale can make the world into a more peaceful place, as countries which promote free trade tend to be democracies, and countries that are democracies are less likely to end up at war with each other (historically, there is some evidence for this claim).

If left alone markets will also naturally produce stability and prosperity. Businesses should therefore be given maximum freedom. Firms, being closest to the market know what is best for their businesses. If we let them do what they want, wealth creation will be maximized, which benefits the rest of society, and the economy as a whole will run more efficiently. This is in contrast to a socialist, planned economy (described below), like the one that existed in the former Soviet Union, where those doing the planning were simply incapable of gaining the vast specialist kind of knowledge needed to work out what people really wanted and make sure that they got it. Inefficiency, food surpluses, gluts of unwanted goods and famines all resulted from this approach. All are, of course, detrimental to human ‘flourishing’.

Too much government intervention (e.g. to tax company income or the pay of top executives) prevents the free market from producing that aforementioned stability and prosperity. So for capitalism to flourish, the state must remove itself from all economic activity except, in the words of Milton Friedman (a famous modern economic theorist who supported free market capitalism), for ‘the military, the courts and some of the major highways’. Notably, education, health, and purveyors of energy like gas and electricity do not feature on his list.

Globalisation* is, for neoliberals, the best method to spread the free market ethos, and in terms of foreign policy is accompanied by – in theory at least – support for the establishment of liberal democracies in as many parts of the world as possible.

*Economic globalisation refers to the spread throughout the world of industrialized production and new technologies promoted by unrestricted free trade and the free movement of capital and labour (potential employees) across national boundaries.

THE ALTERNATIVE : KARL MARX, SOCIALISM, AND MARXIST ETHICS

Marx never wrote anything systematic or substantial on ethics, and even once commented ‘Communists preach no morality at all’. He tended to think of moral theories as simply reflecting the specific interests, demands and situations of different classes at different times. Moralities are class-bound, conflicting, dependent on economic interests, and therefore neither truly ethical nor truly human. Moral codes were therefore not to be treated as either true or false in themselves. For example, in the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels state that, ‘The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.’

Engels [another Marxist theorist] also wrote in a text called Anti-Duhring that, ‘…morality was always a class morality; it has….justified the domination of the ruling class.’

Marx was the most famous critic of capitalist theory. According to Marx, capitalism requires profit and profit requires exploitation – of employer and employees. They are both victims of a system that produces their mutual hostility. In other words, the masters are no more free than the slaves, and it is the system itself that is the problem. As long as man cannot be himself, as long as he is forced to play out a role cast for him by the system, he cannot become the subject of ethics. His moralities are not expressions of his humanity, but reactions to his presently inhuman condition.

Marx therefore proposed socialism as an alternative economic theory. This is an economic system whereby the means of production and distribution are owned by the workers and the state. The prices of goods and wages are fixed by central government instead of being regulated by the market. The whole economy is rationally planned, rather than being determined by the random outcome of private initiatives, and the ownership of private property is abolished as it can give rise to class antagonisms (the Biblical commandment, ‘Thou shalt not steal,’ for example, is only needed in societies based on private property).

Marx regarded the emergence of Communist societies as inevitable, as the proletariat, the ordinary wage earners, eventually rise up against the capitalist class or bourgeoisie to seize the means of production. With the abolition of private property, exploitation and class conflict, a new society would emerge.

Marx’s vision is a highly utopian one: a new morality would also arise under Communism and people would become spontaneously co-operative and dedicated to the common cause. Crime would slowly wither away and there would be no need for a police force. There would also be no need for moral rules and sanctions. Disputes, as Lenin once said, will be settled on the spot, among comrades. The individual and the collective would become one. Both in the work that they do and in others, people would find true freedom and satisfaction, just as artists find inspiration and satisfaction in producing and creating their own work, and in appreciating the work of other artists. In other words, it is only under Communism that human beings can truly flourish.

Of course, the assumption Marx makes here, that there exists a natural inclination to be spontaneously co-operative that is common to all human beings, is highly questionable.

Marx also seems to assume that all social conflict would end once class structures and private property were to disappear. This, again, is highly debatable, and one only needs to consider people’s sexual behaviour within the sphere of private morality to come up with an area where, say, lying, manipulation and extra-marital affairs might still be commonplace.

One last assumption that Marx makes is that capitalism is inherently exploitative. To an extent this may well be true, but perhaps a more regulated form of capitalism, one with checks and balances built into it, may not be. This might be put in place to ensure that large corporations are not allowed to operate sweatshops (see below for more on this), pollute the environment, get away with paying little or no corporation tax, or unduly influence the policies of democratically elected governments.

Such a form of regulated capitalism might also mean that basic amenities and industries, like public transport, health and energy, remain in public [governmental] ownership to ensure that effective services are delivered, even where and when there is no profit to be had. Finally, the financial markets may also need to be regulated to prevent future economic crashes as a result of what the political philosopher Ralph Dahrendorf once called ‘casino capitalism’.

Note that – rather like utilitarianism and Kantian ethics – capitalism and communism can be seen as products of the Enlightenment (see the blog entry on postmodernism for more on this). Both are essentially utopian projects that envisage the establishment of a single worldwide community, one in which an existing diversity of cultures would eventually be displaced by a new civilization based on rationality.

HAYEK, FRIEDMAN AND KEYNES

In the case of Hayek, an Austrian-British economist who became influential after World War 2, economic freedom was a profoundly political and moral force that helped to shape all other aspects of a free and open society, and he was a great believer in the power of Smith’s free-market as a self-regulating and knowledge generating engine to bring about this type of society.

A particular concern of Hayek is that a centralised government is coercive. It forces people to conform to its approach (e.g. by only making the products that it thinks are necessary and useful). So ultimately it curtails individual freedom (‘flourishing’ by another name) and eventually leads, Hayek thinks, to unlimited totalitarian government. His most famous book is called The Road to Serfdom. Serfdom is another word for slavery, and Hayek thought that socialist economies would end up treating us all as serfs. He is also famous for saying ‘The chief evil is unlimited government’.

Milton Friedman was greatly influenced by Hayek and helped to promote his ideas. In the 1950’s they were only supported by a minority of economists but by the 1990’s, neoliberalism had become the ruling economic orthodoxy. Friedman’s own contribution was to focus on keeping inflation low (rather than unemployment), and to insist that only a free-market system could ensure that the right number of goods would be available at the correct price, produced by workers whose wage levels were determined by the free market.

Marxists have responded by arguing that neoliberalism is still exploitative, as all forms of capitalism are, but tries to hide this by dressing up its philosophy in the seductive guise of high-minded ideals like ‘freedom’ and ‘opportunity’ . This kind of message appeals to workers who then fall into the trap of accepting their own exploitation.

Contrastingly, Keynesian economics is regarded as the most viable alternative to free market capitalism. Committed to the market principle but opposed to the free market, John Maynard Keynes (1883 to 1946) was an earlier economist who was sceptical about the ability of the market to correct itself during an economic crisis. So he was more in favour of government intervention. For example, he favoured kick-starting an economy in crisis by increasing public spending. The unemployed could then be paid for their participation in, say, government financed building projects, and in turn would spend their wages, which would increase demand and help to restore a healthier economic cycle. Keynes was also in favour of the state ownership of crucial national enterprises like railroads or energy companies, as it was not always possible to run these services at a profit eg. by providing a rail service or postal service to remote rural areas.

Historically, Keynesian economics became popular because Keynes’s policies helped to bring about an end to the Great Depression of the 1930’s. Prior to that, Adam Smith’s free market philosophy had been in the ascendant, until (as in 2008) investors became overconfident and – in the absence of careful monitoring – overreached themselves, resulting in the great economic crash of that decade. Keynesian economics remained popular until the 1970’s when his policies could not satisfactorily address a problem of stagflation (when high rates of inflation and unemployment occur simultaneously) in MEDCs (More Economically Developed Countries). This was the point at which the ideas of Smith, combined with the theories of Hayek and Friedman (who were also good at promoting them), underwent a major revival.

A problem with taking a Keynesian approach to any modern domestic economic crisis is that economies these days are much more open, so filling any local economy with newly printed money to stimulate demand may only have a limited effect, as much of that money may then simply flow abroad.

RELIGIOUS PERSPECTIVES ON CAPITALISM AND SOCIALISM

Is free-market capitalism compatible with Christian ethics? First of all, a supporter of Situation Ethics, or a Christian who regards Jesus’s emphasis on agape (selfless concern for others) to be of paramount importance in terms of love of neighbour, would be concerned that Smith makes no attempt to temper the selfishness of the typical economic actor. So he seems to be encouraging the type of egoism that both Jesus (and Joseph Fletcher) were opposed to.

However, the Christian theologian D. Stephen Long has drawn attention to the fact that the very title of Smith’s work (The Wealth of Nations) is actually a Biblical phrase taken from Isaiah 60 and 61, so its significance would surely not have been lost on its presumably more Biblically literate original readers. Additionally, Paul Oslington has suggested that Smith’s Calvinist upbringing may have influenced his views, to the extent that although human beings are inherently selfish as a result of the Fall of man, which produced a tendency to sin in them, God himself supplies the ‘invisible hand’ which ensures that collective harmony and prosperity nevertheless result from their decisions. This in turn suggests that Smith saw his system as entirely compatible with his Christian faith.

More recently, Church leaders such as Pope Francis and the Archbishop of Canterbury have been critical of the inequalities and deprivations that seem have resulted in many countries where the modern free-market capitalistic formula of deregulation of the economy, liberalisation (of trade and industry), and the privatisation of state owned enterprises (the well-known D-L-P formula) have all taken place. Both in MEDC’s (More Economically Developed Countries) and LEDCs (Less Economically Developed Countries), a widening gap seems to have opened up between a rich elite and the poor (e.g. as represented by the famous Russian oligarchs). In their recent books, The Spirit Level and The Inner Level, epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett have found that along with this gap, the more unequal a society is, the more people suffer from a variety of physical and mental health problems, such as obesity and depression. Additionally, drug abuse tends to be rife, rates of imprisonment and teenage pregnancies are higher, social mobility is less possible (making it harder for people to better their lot in life), trust between citizens is lower, and violence is more endemic. In other words, outcomes are significantly worse in more unequal rich countries like the US and UK. Deregulated markets also tend to put a strain on family life, as both parents typically have to work long hours. It is therefore unsurprising that – according to the philosopher John Gray – by 1991 Britain had the highest divorce rate of any EU country, one that was only comparable to that of the United States. Given that America and Britain both serve as exemplars of the free market philosophy, in the light of Wilkinson and Pickett’s research, it seems reasonable to draw the conclusion that this philosophy is hardly conducive to ‘flourishing’.

Overall, it is therefore also fair to say that these two church leaders are expressing valid concerns about what happens when markets are unregulated in the manner suggested by Smith and advocates of neoliberalism.

Interestingly, there has been traditionally been strong support for socialism from within Christianity. The theologian D. Stephen Long, for example, has emphasised the role that koinonia or ‘things held in common’ had within the early Christian community, arguing that ‘socialism’ was Christian before it was ‘made scientific and fundamentally distorted by Marx and Engels.’ Here Long is referring to the fact that Jesus and his disciples seem to have lived communally, sharing a common purse and giving what they had to the poor. Furthermore, according to the teaching of Jesus in the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew 25, we are to be judged on our concern for others, with the ‘sheep’ enjoying the reward of eternal life because they gave food and drink to the hungry and thirsty.

Additionally, Ambrose, a fourth-century Archbishop of Milan wrote that when you give to the poor, ‘You are not making a gift of your possessions to the poor person. You are handing over to him what is his. For what has been given in common for the use of all, you have arrogated to yourself.’ This reflection subsequently became part of the Christian tradition, with Aquinas going so far as to say that, ‘it is not theft, properly speaking, to take secretly and use another’s property in the case of extreme need: because that which he takes for the support of his life becomes his own property by reason of that need.’

Commenting on these teachings in his book The Most Good You Can Do, the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer states the following:

‘Surprisingly to some, the Roman Catholic Church has never repudiated this radical view and has even reiterated it on several occasions. Pope Paul VI quoted the passage in which Ambrose that what you give to the poor is already really theirs and added, in his encyclical Populorum Progressio, “We must repeat once more that the superfluous wealth of rich countries should be placed at the service of poor nations. The rule which up to now held good for the benefit of those nearest to us, must today be applied to all the needy of this world.” On the twentieth anniversary of Populorum Progressio, Pope John Paul II said it again, in his encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, and Pope Francis has indicated his support for this doctrine too.’

Also worthy of mention is Pope Francis’s condemnation of ‘the idolatry of money’ (a reference to the second commandment – ‘You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above or that is on the earth beneath’). Commenting on rising inequality in many societies – the gap that exists between the rich and the poor – he has also criticised the policy followed by many governments of not interfering with the way that businesses operate. This led the late Rush Limbaugh, at the time one of America’s most famous radio talk-show hosts, to accuse the Pope of ‘pure Marxism.’

Moving on, the Liberation Theology movement that has been popular in South American countries is inspired by Jesus’s teaching in Luke to ‘set free the oppressed’. Accordingly, supporters of this movement have regarded themselves as having a Christian duty to oppose governments that exploit their citizens, to the extent of torturing and murdering them. And so if El Salvador in the late 70’s and 80’s can be seen as an example of capitalistic excess (as it was a country with a military dictatorship that supported a wealthy elite of coffee plantation owners while the native Indian population were mired in poverty), then it seems as if Christian religious ethics, which has traditionally concerned itself with the poor and downtrodden, must be said to have more in common with socialist thinking, especially when one factors in Biblical injunctions against usury (lending money at interest) and Jesus’s insistence that one cannot love God and money and that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God.

As was pointed out in a previous blog entry on equality, towards the end of his life, Martin Luther King also came to think of capitalism in this way. According to a study by James Cone, in spite of the success of the civil rights movement in ending racial segregation in the south, King eventually came to realize that – as Malcolm X had pointed out – there was little point in black Americans being able to eat at the same lunch counters as whites if they were unable to afford the meal. As Cone narrates:

‘Martin reflected upon socialism even more seriously when he realized that the black poor (as well as the white poor, a reality that surprised him) were getting poorer and the white rich richer, despite the passage of the much celebrated Civil Rights Act and President Johnson’s War on Poverty. He became explicit about the need for economic equality, an “Economic Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged” which would guarantee a job or an annual income for all Americans…But because he was still deeply aware of the harm that a “communist smear” could do to the civil rights movement, he was very cautious about the dangers of speaking positively of “democratic socialism.” “Now this means that we’re treading…in very difficult waters, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with the economic system of our nation,” he said in a speech to his staff. “It means that something is wrong with capitalism.” During staff retreats, he often requested that tape recorders be switched off, so he could express his views frankly and honestly about the need for a complete, revolutionary change in the American political economy, replacing capitalism with some form of socialism. What we have had in America is “socialism for the rich and free enterprise for the poor,” Martin said often.’

What the above example perhaps demonstrates is that issues to do with discrimination cannot be separated from that of economic inequality. If the latter problem is not addressed, progress in the former is going to be more negligible.

Further criticisms of neoliberalism, this time ventured from a Buddhist perspective, are to be found in Matthieu Ricard’s mammoth 850 page multidisciplinary study of altruism.

Ricard is a rather unique character. His father was Jean Francois Revel, a former philosophy professor, journalist and enthusiastic proponent of free-market economics. At one point Ricard seemed destined for a career in cellular genetics but instead, in 1972, ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist monk, and since then has spent much of his time in the Himalayas. But this has not turned him into a benign but unworldly out-of-touch recluse. Ricard’s background in both Eastern and Western Philosophy positions him more than adequately to survey what is essentially ethical territory, and his reading has been interdisciplinary and thorough, taking in the most relevant up-to-date scholarship across a broad spectrum of academia. So what does he have to say?

First of all, Ricard takes issue with an assumption found in a lot of Western philosophical writing (his examples include Hobbes, Adam Smith and Ayn Rand) that human beings are selfishly and unalterably egocentric. This is as assumption that he shows to be false by drawing attention to the abundant, carefully calibrated and mutually reinforcing studies in the field of psychology which demonstrate our ability to empathise and act (from a surprisingly young age) in what seems to be a purely altruistic and spontaneously compassionate manner, uncontaminated by mercenary motivations. Research on the animal kingdom further indicates that such behaviour is widespread there too, which in turn suggests, perhaps counter-intuitively, that these dispositions are integral to our evolutionary heritage. Economic policy-making based on the model of homo economicus – the view that humans are narrowly individualistic, rational but self-interested creatures – therefore becomes suspect in the light of this research.

Ricard goes on to insist that our capacity to act in a benevolent manner (where the motive is simply to promote the well-being of others) can be built on and further cultivated both inwardly and outwardly. Specifically, he refers to surveys of neuronal plasticity affirming that the brain can be structurally modified through meditation practices specifically designed to spontaneously arouse and reinforce our potential for compassion. Interestingly, Ricard has been called ‘the happiest man alive’. This is because, as an advanced meditator, scans of his own brain have shown increased activity in the regions associated with what states of sublime contentment.

Additionally, Ricard highlights research indicating the possibility of a transformation brought about through environmental changes that might helpfully stimulate the expression of some genes while repressing others. Put more simply, and with reference to just one example (in fact Ricard’s book contains lots of suggestions to make the world a better place in this respect), regulation designed to rein in and curtail the excesses of neoliberalism, together with a drive to persuade the more privileged of the need to do something to reduce economic inequality, might, he believes, prevent genes associated with anxiety and other negative mental states from becoming active.

Of course, for Ricard, meditation practices that are based on the cultivation of compassion (karuna in Mahayana or ‘Greater Vehicle’ Buddhism) would be the method by which it is possible to become more empathic and altruistic. But what he might have overlooked is the fact that these practices have already been co-opted by neoliberalism as a means of helping people to cope with the instabilities and insecurities, the remorseless stresses, that inevitably accompany this form of late period capitalism, so that they do not then start to question the system itself. Mindfulness (or ‘McMindfulness’ as it has been dubbed) is now big business. Corporate leaders and employees at all levels are encouraged to adopt mindfulness practices (that can specifically include extending compassion and lovingkindness to oneself, one’s colleagues and customers) in staff training courses. And for school pupils subjected to a constant regime of testing, the method is also touted (and often introduced by inexperienced teachers with little formal training, or even via an iPhone App) as a way to address the mental health issues that are becoming increasingly prevalent among teenagers. But perhaps these contemplative techniques do nothing more than permit neoliberalism to perpetuate itself, as THIS article explains.

EVALUATING CAPITALISM (AND SOCIALISM), CONSUMERISM AND THE ETHICAL IMPACT OF GLOBALISATION

The failings of socialist ‘utopias’ are already well-known. For example, in the former Soviet Union, where central planning replaced markets, millions of lives were lost through totalitarian terror, endemic corruption, and environmental degradation. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong’s government policies caused an even greater number of deaths, up to 30 million of China’s own citizens, and the Communist Khmer Rouge regime is estimated to have killed off 1.7 million citizens of its own nation in Cambodia, thus confirming Hayek’s worst fears.

As a consequence, capitalism is now frequently presented as the only viable economic system, given that Marxism has lost so much credibility in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dilution of Communism in China. According to the late Mark Fisher (an author and blogger known as K-Punk who also taught Philosophy and Religious Studies in a sixth form college), the quotation “it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism,” falsely attributed to both Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Zizek , encompasses the present state of affairs.

In his brilliant global history of ethics The Quest for a Moral Compass, Kenan Malik also writes in a similar vein:

‘By 2008…the possibility of change, at least in the way that Marx would have understood it had become negligibly small. The depth of the economic crisis led to talk of ‘a crisis of capitalism’. And yet there was no political challenge to capitalism. Worker’s organisations had been destroyed, the left had imploded, as had the idea that there could be an alternative to the market system. The resurrection of Marx challenged none of this. Those who turn to Marx these days look upon him not as a prophet of capitalism’s demise but as a poet of its moral corruption.’

But is capitalism in its neoliberal form faring any better? Below it will be shown to be exploitative in the case sweatshop employees in China, just as it has of the poor in the USA and Latin America, supportive of sympathetic autocratic regimes (El Salvador, see also Chile and the notorious ‘Chicago Boys‘), responsible for exacerbating economic inequality in many countries, and is, as Ricard has shown, based on a false and damaging view of human nature.

Interestingly, in drawing attention to the ‘pernicious effects that inequality has on societies‘, Wilkinson and Pickett (see above) also highlight the link that exists between excessive consumerism and inequality. In particular, they challenge the perceived view that consumerism is driven purely by forces of material self-interest and acquisitiveness, and instead show that it is more an expression of status anxiety. In a quest to ‘keep up with the Jones’s’, those who are less well-off will thus save less and borrow more, max out on credit cards and fall into debt, as well as work longer hours, all so as to be able to emulate others and not feel as if they are getting left behind. In other words, more unequal societies summon up an almost neurotic urge to shop and consume in their citizenry. The products that are purchased also tend to be selected for their prestige value and because they look good to others, rather than for their usefulness.

In turn, the constant and sustained economic growth and competition that all this demands is, Wilkinson and Pickett emphasise, very damaging to the biosphere, as it then becomes increasingly difficult to keep economic activity within sustainable levels. Contrastingly, more equal societies engender a wider sense of social responsibility in their populations, so that a higher proportion of waste gets recycled, and prominent business leaders are more strongly inclined to encourage their governments to comply with international environmental agreements. Additionally, health, happiness, friendship and community life are foregrounded and valued in societies less devoted to a cult of consumption. Wilkinson and Pickett’s research therefore adds further weight to the view that, at the very least, the more extreme neoliberal version of capitalism creates a culture hallmarked by an excess of consumption, one that nevertheless – when measured according to utilitarian terms of reference – does not result in greater collective happiness and flourishing.

Staying with the issue of capitalism, consumerism and flourishing, in an influential article and book, the political philosopher Michael Sandel has argued that free-market capitalist values have been allowed to invade too many areas of public life that they should be excluded from. One of many examples he gives is of pupils in US schools being forced to watch a TV news show for 12 minutes a day which includes two minutes of commercials featuring products such as Pepsi and Snickers. In return the school is provided with free televisions, video equipment and satellite links. Another is of school grade cards being issued in jackets bearing a promotion for McDonalds including a cartoon of Ronald McDonald. According to Sandel, this is wrong because the purpose of public schools is to inspire students to reflect critically on their desires and to restrain rather than indulge them, to cultivate the virtues of citizenship rather than consumerism. In other words, free market capitalism is corruptive of the shared values of a community. It is also coercive (cash strapped schools are forced to accept corporate sponsorship because state funding is inadequate). So if people and organisations are forced to enter the marketplace then we can no longer talk about a market being free.

John Gray has also been critical of how, in a Kantian sense, capitalism and consumerism work together to erode our perceptions of those we interact with most intimately, so that cease to see them as ‘ends in themselves’: ‘In a culture in which choice is the only undisputed value and wants are held to be insatiable, what is the difference between initiating a divorce and trading in a used car? The logic of the free market… is that all relationships become consumer goods.’

A further issue worth exploring is whether neoliberal policies have benefited LEDCs. Here, once again, the answer is ‘no’. For instance, Jacob Rees-Mogg (at the time of writing the new UK Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy) once tweeted that ‘free trade is always the key to prosperity’ in connection with the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Unfortunately, this claim is false. For poorer countries (Peru, Vietnam in this instance), free trade can be damaging. As the economist Ha Joon Chang has noted, when poor countries open their borders to free trade, infant industries within them often find themselves unable to compete with better established TNCs (Trans-National Corporations), and so end up going out of business. Contrastingly, economies that resist implementing free trade in a wholesale manner (for example, by not privatising state enterprises that deliver essential services, or keeping import tariffs to protect their infant industries) often perform better economically.

More generally, in his book False Dawn: The Delusions of Global Capitalism, John Gray looks in detail at four countries that have experimented with neoliberal policies: the USA, UK, New Zealand and Mexico. In each instance, the imposition of these policies demonstrably increased economic inequality (thus confirming Wilkinson and Pickett’s research), and reduced social mobility and cohesion. For example, according to the Rowntree Report on Income and Wealth, inequality in the UK increased dramatically and quickly between 1977 and 1990, a period during which the poorest income groups ceased to benefit from economic growth, and there was a threefold increase in the proportion of the population earning less than half of the national income. However, by 1984-85, the richest 20% of earners enjoyed a 43% after tax share of that income, the highest since the end of the World War 2. Meanwhile, in New Zealand a previously non-existent underclass was created following the introduction of neoliberal policies, while in Mexico the size of the middle classes was substantially reduced, and the very poorest were driven into a state of even more abject poverty.

But what of the USA, a country that has both fully embraced and preached the free market philosophy? Gray takes the view that ‘it has gone far towards establishing itself as the unofficial American civil religion’ but that the results have been to ‘bring about levels of economic inequality unknown since the 1930’s* and far in excess of those found in any other advanced industrial society today, [and] has encompassed an experiment in mass incarceration**, accompanied by an elite retreat into walled proprietary communities***’ that has left the country deeply divided socioeconomically. He then goes on to add that, ‘in late twentieth-century America, the free market has become the engine of a perverse modernity. The prophet of today’s America is not Jefferson or Madison. Still less is it Burke. It is Jeremy Bentham, the nineteenth-century British enlightenment thinker who dreamed of a hyper-modern society that had been reconstructed on the model of an ideal prison.‘

*Gray notes that although productivity had risen over the two decades up to 1998 – the date of the publication of the first edition of False Dawn – the incomes of the majority (eight out of ten) had actually fallen.

** Gray’s figures are not recent but he notes that by the start of 1997, around one in fifty adult American males was in prison, while about one in twenty was on parole or probation, a rate that is ten times that of European countries.

*** False Dawn was first published in 1998. Back then, Gray estimates that some 28 million Americans – over 10 per cent of the population – were living in privately guarded buildings or housing developments.

Another intriguing but also disturbing effect of neoliberalism is its tendency to allow characters with narcissistic and psychopathic personality profiles to ascend to positions of prominence in business (a tendency that is, perhaps, also mirrored in politics, as revealed in the presentation by Ian Hughes that features in THIS previous blog entry). According to Clive Boddy (in his book Corporate Psychopaths), as deregulation in the UK, US and elsewhere has loosened restraints, characters with this kind of profile have increasingly been unleashed in the world of business. Boddy in fact claims that genuine psychopaths, who typically lack any kind of conscience or ability to empathise with others, have risen to senior positions within modern financial corporations, from where they have then been able to influence the moral climate of the whole organisation and wield considerable power. In a 2011 interview with the journalist Brian Basham, he has also gone as far as asserting that they ‘largely caused the [banking] crisis’ in 2008.

Such claims may seem a little outlandish, until one considers a study at the University of Surrey which found that the personality traits of thirty-nine senior managers matched, and even exceeded, the narcissistic, dictatorial and manipulative tendencies typically exhibited by psychiatric patients and psychopaths, all concealed behind a veneer of superficial charm and charisma. Jeff Skilling, the infamous former CEO of the multinational Enron, is arguably someone who might possibly fit this description. A self-declared admirer of Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene and Herbert Spencer’s phrase ‘survival of the fittest’, Skilling remains notorious for having implemented a ‘Rank and Yank’ appraisal system involving the constant monitoring of employees and the sacking and public humiliation of up to one-fifth of those with the lowest production figures every year. It is also surely not without significance that in the article which features the interview with Boddy, it is revealed that one major investment bank was actively seeking to appoint potential employees with a psychopathic profile to senior roles.

John Rawls (1921 – 2002)

Rawls is renowned for an influential thought experiment that he described in the above publication. He asks us to imagine that we are to become a member of a new society but presently know nothing about what part we will play in it. For example, we don’t know if we will be rich, poor, able-bodied, good looking, male, female, intelligent, unintelligent, talented or unskilled, and we won’t know which ethnic group we will belong to or what our sexual proclivities might be. Rawls thought that in our currently prior state (which he called the Original Position), where we have to collectively decide in advance from behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ on the rules that will govern our new world, that we would be rationally attracted to choosing ones that could improve our situation if we ended up disadvantaged in some way. In other words, we would opt those that would produce a relatively egalitarian society.

Specifically, he thought that it would be rational to accept two fundamental principles: those of Freedom and Equality. The first principle is one that would maximise a range of freedoms for all citizens, such as being able to vote for who governs you and extensive freedom of expression, while the second, which is also called the Difference Principle, would ensure more equal levels of wealth and opportunity. For example, although some people might be paid very high salaries, this would only be allowed if lower paid workers somehow received more money because of this arrangement, more than they would if the highest paid citizens were paid less. Rawls also thought that those who are endowed with natural talents, such as intelligence or sporting ability, were not necessarily entitled to more money, as being blessed in this way is mainly due to luck and good genes.

Overall, Rawls’ theory implies that the fairest and most just society might not be one based on free market capitalist principles because of the excessive economic inequalities that the free market currently permits.

CAN HUMAN BEINGS FLOURISH IN THE CONTEXT OF CAPITALISM? UK CASE STUDY ONE: EDUCATION

It may seem odd to select the education system itself as an example. But then, neoliberalism is, according to Guardian journalist George Monbiot, an ideology that operates covertly, under the radar so to speak. This is revealed by the fact that while almost everyone knows what Marxism is, ‘mention neoliberalism in conversation and you’ll be rewarded with a shrug. Even if your listeners have heard the term before, they will struggle to define it.‘ So it is no surprise that its influence on schools has gone undetected.

In this particular instance, neoliberal mission creep can be traced back to the late 1980’s. In her A Memoir: People and Places, Mary Warnock writes as follows:

‘The consequence of the 1988 Education Act in so far as it was concerned with school education, was to introduce the idea of competition between schools, and choice for parents. The league tables showing the academic achievements of schools alongside one another were supposed to enable parents to choose the best schools. The free market would operate. Schools which performed badly would not be chosen by parents, and so would ultimately wither away. This was the original idea. (no one gave thought, apparently, to what would happen to children who were pupils at these bad schools while they were in the process of withering away).’ [Warnock herself was worried about the impact on the education of children with special needs].

‘This part of the 1988 Act was derived largely…from a personal vendetta of Margaret Thatcher’s, this time against the teaching profession. Teachers could be judged, she thought, by the academic results of their pupils; the operation of the free market would succeed in the end in eliminating those schools where the teachers were bad; or market competition would cause those schools to get rid of their bad teachers and employ good ones, so that they would become good schools. This was the theory, enthusiastically propounded by Kenneth Baker, and close to Margaret Thatcher’s own heart.’

Later in the chapter and still on the subject of the 1988 Great Educational Reform Bill, and the establishment of the University Funding Council, Warnock notes that the latter new body was dominated by representatives from the business world who were largely in thrall to the view that the goal of higher education should be to satisfy the needs of commerce and industry. The preceding White Paper had made it clear that it was up to Whitehall and not students to decide which subjects were worthy of study: ‘The Government considers student demand…to be an insufficient basis for the planning of higher education. A major determinant must be…the demands for highly qualified manpower.’ In a nutshell, the purpose of universities should primarily be to serve ‘the world of business’.

Warnock goes on to conclude that ‘the condition to which higher education was reduced was, I think, one of the worst effects of Thatcherism…the concept of learning, the respect for higher education for its own sake, as something intrinsically worth having, an essential part of any civilised society, had been thrown out; and this largely because of her own detestation of academics.’

NOTE: for a much fuller exploration of the impact of neoliberal policy on higher education both here and in other parts of the world, see THIS PREVIOUS BLOG ENTRY (a review of Martha Nussbaum’s Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities).

Fast-forward to 2009 and the publication of Mark Fisher’s influential Capitalist Realism : Is There No Alternative? The title of the book is based on “the widespread sense [following the collapse of the Soviet Union] that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.” The effect of this has been to subvert discussions from those in which capitalism is considered as just one of many potential ways of operating an economy, to one in which political considerations operate solely within the confines of the capitalist system.

Fisher regards the bank bailouts following the 2008 economic crisis as an example of capitalist realism in action, reasoning that they occurred largely because the idea of allowing the banking system to fail was unimaginable to both politicians and the general population. Due to the banks intrinsic value to the capitalist system, the influence of capitalist realism meant that such a failure was never considered an option. As a consequence, Fisher observes, the neoliberal system survived and capitalist realism was further validated. According to Fisher, capitalist realism-type thinking can and should be challenged on the basis that it is not realistic at all.

Firstly, he points out that it ignores the possibility of a future environmental catastrophe because it is based on the decidedly unrealistic view that the earth’s resources are infinite, that capitalism’s need for constantly expanding markets will not eventually use them up, and that environmental problems simply require ‘market solutions.’ The effect is to treat the ecosystem as if it is a business providing services to humanity. Additionally, Fisher notes that a correlation has been found between rising rates of mental distress and illness and neoliberal economics as practised in the UK, USA and Australia. For example, in Britain, depression is now, Fisher claims, the condition that is most treated by the NHS. He argues that this is due to the instability of the modern working environment, in which there is no longer any long term job security.

The pressures of constant evaluations that employees (and school pupils!) are repeatedly subjected to additionally results in an unprecedented level of bureaucracy and excessive paperwork , which mainly involves employees having to prove that they are doing their jobs properly. Fisher sometimes refers to this process as ‘Market Stalinism’, as it is more readily associated with planned economies like the ones favoured by Marx, which are typically criticised for being excessively bureaucratic.

In state sector teaching, rigidly formatted and excessively detailed lesson planning is one manifestation of this bureaucracy at work and is part of the machinery of self-surveillance (as the documentation evidences the efficacy of the teaching). However, given that teachers these days are held to account for pupil’s public examination performances, the teaching itself tends to be geared passing the examinations. Narrowly focused ‘exam drills’ replace a wider engagement with subjects.

A further point (not mentioned by Fisher), is that the logic of the free-market has also been applied to school budgets. A noted though not widely reported effect of this has been that experienced but more expensive older teachers have been eased out of their jobs under the guise of a process known as ‘capability’, whereby the senior management of schools observe the teacher, judge the lesson to have been inadequate, and instigate a process that ends with the teacher leaving or resigning in many instances. While in some cases the teacher’s competence may have rightly been called into question, the consensus of the now defunct Times Educational Supplement forum (a formerly very active online community of teachers) was that this procedure was being utilized by schools as a pretext to save money.

Recruitment policies were also alleged to have been adjusted. Given that younger teachers cost less to hire than older ones, and are generally perceived to be more compliant and prepared to work unreasonably long hours, they tend to be the ones appointed at interview.

Meanwhile, when it comes to pupils, Fisher states that ‘it is not an exaggeration to say that being a teenager in late capitalist Britain is now close to being classified as a sickness.’ One reason for this is, of course, because teaching to the test requires pupils to be constantly evaluated. Additionally, families are buckling under the pressure of a neoliberalism that requires both parents to work (and frequently to work long hours as neoliberalism promotes a 24/7 working culture). A consequence of this is that teachers are now increasingly required to act almost as surrogate parents in their role as profferers of pastoral and emotional support.

Fisher goes on to conclude, like Wilkinson and Pickett, that, ‘The ‘mental health plague’ in capitalist societies would suggest that, instead of being the only social system that works, capitalism is inherently dysfunctional.’

Finally, and moving on to 2022, the candidates for the leadership of the Conservative Party, Rishi Sunak and Elizabeth Truss, both made comments that are relevant to this case study during their respective campaigns. As has previously been mentioned, what they said has already been evaluated in the review of Nussbaum’s Not for Profit, an assessment that – along with the points made above – suggest that largely unregulated capitalism is having a profoundly damaging effect on human flourishing in the sphere of education.

CAN HUMAN BEINGS FLOURISH IN THE CONTEXT OF CAPITALISM? UK CASE STUDY TWO: SHAREHOLDERS, STAKEHOLDERS AND THE ENERGY CRISIS

First of all, this issue needs to be framed within the context of the limits of corporate social responsibility, and specifically what might be seen as the competing pressures exerted by shareholders and stakeholders on how large, often multinational businesses, conduct themselves. So a lengthy preamble will be required, one which describes the relevant moral landscape and the responses that might be made to it by subscribers to the relevant normative ethical theories, before moving on to noting how, in formulating its approach to the energy crisis, the Conservative government has, in true neoliberal fashion, largely overridden stakeholder concerns.

Shareholders versus Stakeholders Part One: Milton Friedman

A shareholder is a person (or institution) who, in return for investing money in a company, legally owns a portion of it in the form of shares. In return for this they may receive a dividend, an annual payment made from any profits the company makes.

A stakeholder is anyone who is affected by the activities of a company, for example, employees, suppliers, customers, or the local community (who may suffer any adverse environmental effects of the company’s actions).

Milton Friedman has famously and controversially argued that – when deciding which of these two constituencies to favour – the sole responsibility of a corporation (or the corporate executives running it) is to make profits for its shareholders. He considers that when a company or corporation gives to charity this means that it may not be fulfilling its responsibility to its shareholders to maximise profit. More generally, if corporate executives cut into profits to exercise their social responsibilities that they are not legally required to fulfil (examples might be to reduce any pollution that a company causes through its activities beyond what the law requires, or to deliberately hire staff from an ethnic minority according to the principle of affirmative action), this is like taxing the shareholders to redistribute their wealth, something which is the business of government and not the company itself. He also argues that a corporation is not a person and that it cannot therefore be held morally responsible for its actions in the way that individuals can. However, he does believe that decision makers within the company are accountable for their decisions and that they should not behave in a fraudulent or illegal manner.

This view has been criticised by R. Edward Freeman on the grounds that big corporations often contribute to political parties, who if they win elections might return the favour by not making laws about the environment and the rights of employees that are strict enough to ensure that stakeholders are legally protected from the worst effects of business activity, which might also include price gouging (overcharging for essential goods and services – a criticism that has been made of UK energy suppliers), and price fixing (where participants on the same side in a market agree to buy or sell a product or service at more or less the same price).

The philosopher Noam Chomsky has also been critical of the highly unethical behaviour of large transnational corporations (TNC’s) who put profits over and above any sense of responsibility to their own employees, their consumers, or the environment. Chomsky maintains that corporations are obliged to act in ways that we would regard as pathological (i.e. dangerous and psychopathic) if that behaviour was exhibited by a human being. Chomsky’s comments are based on the research of psychologist Robert Hare. According to Hare, large corporations are singularly self-interested, irresponsible, manipulative, lacking in empathy, have no conscience, experience no guilt about their actions, and will lie readily and relate to others in a superficial manner. For example, they set out to destroy their competitors and are not especially concerned about what happens to the general public or the environment as long as people are buying their product. So in the documentary movie The Corporation, Chomsky can be seen to disagree with Friedman’s view that corporations are not persons and should not be treated as if they are (with all the moral responsibilities that being a person entails). For Chomsky, multinational corporations are dangerously amoral, and the public need protecting from them in the same way that they might need protecting from a dangerous psychopath.

Another problem with Friedman’s business philosophy is revealed when we look more closely at what happens when it is actually enacted, something which is possible in the case of the US and UK.

Since the 1980’s, when neoliberal policy-making that dovetails with Friedman’s thinking has been influential in both countries, companies have been put under increasing pressure to deliver high short-term profits (otherwise they may place themselves at risk of a hostile takeover from a Gordon Gekko-type character). Gekko is the protagonist in the Oliver Stone movie Wall Street who famously declared that ‘Greed is good’.

The easiest way for the CEO (Chief Executive Officer) of a company to enable short-term profits to be made is simply to cut costs, something that can be achieved by reducing the workforce through redundancies, freezing salaries, lowering overheads (like paying for employee pensions, cutting investment in Research & Development, and selling off less profitable arms of the business. This ‘slash and burn’ approach is faithfully depicted in Stone’s movie.

So what has been happening is that CEO’s have been paid astronomical salaries to achieve these short-term profits (in a practice known as ‘shareholder value maximisation’) even at the cost of product quality and worker morale. This practice has left very few resources with which the company can invest in things like new machines, research and development, and staff training. And by the time the company gets into trouble, the CEOs who enacted this policy will often have moved on. Given what has already been noted about corporate psychopathy at the managerial level, these business practices could be examples of psychopathy in action.

To convey an impression of how serious this problem is, according to the economist Ha Joon Chang, in the UK, the average period of shareholding, which had already fallen from 5 years in the mid-1960’s to two years in the 1980’s, plummeted to about 7.5 months by the end of 2007. Additionally, Chang notes that between the 1950’s and 1970’s (when Keynesian economic policies were in the ascendant) about 35-45% of corporate profits were given to shareholders in the form of dividends. But between 2001 and 2010, the largest US companies handed over 94% of their profits, while the top UK companies gave away 89% of theirs.

Followers of the main teleological and deontological ethical theories might also criticise the view that the only moral responsibility a corporation has is to its shareholders. For example, a follower of Kantian Ethics may argue that stakeholders should be treated not as a means to an end (profit) but as ends in themselves by corporate executives, a point which particularly applies to employees of a company, as everyone who works in one would be considered to be part of a ‘kingdom of ends’, a community of rational, autonomous beings who deserve equal treatment simply because they are rational and autonomous. Meanwhile, from a Benthamite perspective, his hedonic calculus includes remoteness, extent, duration and fecundity. Quite obviously, actions taken to increase profits that adversely impact employees as stakeholders would not be regarded as morally justifiable in terms of extent (who is affected by a moral decision). The factor of remoteness (how far off in time the pleasure is) also comes into play when the greater long-term interests of a company are damaged by the pursuit of short-term goals. If, in the longer term, the company becomes insolvent or is reduced to a shadow of its former self, then any ‘pleasures’ experienced through the achievement of those aforementioned goals are likely to be short-lived (duration), and are therefore unlikely to generate further pleasures (fecundity).

Whistle-Blowing

Another issue that can arise in relation to business practice and shareholder/stakeholder interests is that of ‘whistle-blowing’. This happens when an employee within a company discovers an illegal or harmful practice that the company is engaging in and makes the news public. A famous example is Karen Silkwood, a US plutonium plant worker who in the early 1970’s exposed lax health and safety practices at her organization and who subsequently died in a car crash, prompting persistent rumours that she was murdered.

Under health and safety law in the UK, according to the government’s Health and Safety Executive website , ’employers are responsible for managing health and safety risks in their businesses.…It is an employer’s duty to protect the health, safety and welfare of their employees and other people who might be affected by their work activities. Employers must do whatever is reasonably practicable to achieve this. This means making sure that workers and others are protected from any risks arising from work activities.‘ An example of when this duty is not observed might arise if, for example, noise-cancelling headgear is not issued to employees undertaking roadworks, who would therefore run the risk of damaging their hearing or developing tinnitus. HSE guidance in such circumstances is listed HERE. Obviously, as far as the OCR syllabus is concerned, all this has a bearing on ‘the contract between employee and employer.’ Again, according to the government’s website, ‘If workers think their employer is exposing them to risks or is not carrying out their legal duties with regards to health and safety, and if this has been pointed out to them but no satisfactory response has been received, workers can report this to HSE.’

From the perspective of rule utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill’s Harm Principle is of relevance. With respect to this Principle, people should be at liberty to live their lives in however manner they wish (and even engage in acts of self-harm under certain circumstances) provided that others are not physically harmed by whatever they get up to. So it might also be appealed to when corporate activity harms a wider stakeholder community. On the other hand, in revealing activity of this kind, whistle-blowers run the risk of losing their job, and may also diminish their prospects of securing future employment as a result of having acquired for themselves a reputation as a troublemaker.

Given the rule-governed duties and obligations that one might also have with regard to one’s nearest and dearest (e.g. look after your own family), rule utilitarianism in its strong format might therefore lead to a conflict of rules, so that no clear-cut decision can be made. Mill, however, advises that clashes of rules can be overcome through a direct appeal to the utility principle, in order to decide which rule takes priority. In this instance, given the greater number of stakeholders affected by illegal or harmful practices, a purely Benthamite assessment would suggest that the whistle should be blown, unless a greater number would be adversely affected, as might happen if the business was to, for example, close a sweatshop and dispense altogether with its workforce rather than improve conditions for them.

Alternatively, when it comes to Kantian ethics, the matter is arguably more clear-cut, as the love that is experienced for one’s family should be set aside in favour of the wider boundaries of ethical concern encompassed by the categorical imperative. For Kant, ethical actions should be performed with a ‘good will’. That is, they should be free of selfish motives. Family considerations are more limited in this respect, as encapsulated by the expression ‘blood is thicker than water’. Given Kant’s insistence that the boundaries of moral concern should be extended to all rational beings, as expressed in the second formulation of the categorical imperative, according to which such beings are to be regarded as ‘ends in themselves’, again this would entail that the whistle should be heard.

One interesting divergence in the application of Utilitarian and Kantian thinking to whistle-blowing may nevertheless arise when the blower is seeking to expose an issue to do with animal welfare. The maltreatment of animals in the food industry or with respect to medical research involving vivisection are two scenarios that may cause employees to consider bringing this to the attention of the wider public. Bentham was, of course, one of the first Western philosophers to deem the suffering of animals worthy of moral consideration. Many other philosophers, including Kant, thought that as animals were unable to reason or to speak, they had no moral status. But Bentham was aware that Nature had not only ‘placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure’ but animals as well. He was keenly aware that, like us, they were in possession of nervous systems and could feel pain. As he put it, ‘…the question is not, Can they reason? Nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer? For Bentham, the answer to this last question was a definite ‘yes’.

Mill broadly agreed with Bentham:

‘Granted that any practice causes more pain to animals than it gives pleasure to man; is that practice moral or immoral? And if, exactly in proportion as human beings raise their heads out of the slough of selfishness, they do not with one voice answer “immoral,” let the morality of the principle of utility be for ever condemned.’ – “Whewell on Moral Philosophy”, in Collected Works, vol. X, pp. 185-187

Among contemporary utilitarians, Peter Singer is an impassioned advocate of animal welfare, and he labels those human beings who exhibit no moral regard for animals as ‘speciesists’, in doing so likening them to racist white slave owners. Singer is also at pains to cite evidence demonstrating that some animals are in possession of ‘personhood’, a level of self-awareness indicative of rationality. For example, in the third edition of his book Practical Ethics, Singer provides examples of chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans who have mastered sign language, as well as other examples of chimpanzee behaviour that involve the deployment of conceptual thought.

So a potential whistle-blower motivated by utilitarian considerations may very well end up acting on their concerns. But then so might a modern Kantian if, on the basis of Singer’s evidence they were to extend the boundaries of his ‘Kingdom of Ends’ to include animals, such as those mentioned by Singer, as well as African Grey Parrots, all of whom have exhibited communicative abilities that, in turn, are suggestive of an ability to reason. In summary, at least some animals deserve to be afforded the same moral status as stakeholders.

Moving on, two of Thomas Aquinas’s Primary Precepts in his Natural Law theory are to do with preserving life and living in a community. Companies who operate in a manner that disregards the health and safety of their employees, as sweatshops often do (see below), and that fail to recognise that they are part of a wider community, would be condemned according to these principles.

Both Kant and Aquinas would also consider a failure to address the problems created by negative externalities (external costs, created by the company but borne by someone else) to be immoral. One example of this was the decision of the Ford motor company not to rectify a design flaw in the fuel tank of its Pinto model because bosses calculated that it would be cheaper to pay compensation to the victims who would have died or been badly burned as a consequence of accidents that caused the tank to ignite. Clearly this decision violates the respect for life that is so central to both of these deontological theories.

For Utilitarians who are followers of Jeremy Bentham, actions which maximise the greatest happiness of the greatest number in terms of their consequences are to be preferred, which makes it inevitable that the wider happiness of stakeholders (a category that would include animals in some instances) must be considered. Similarly, someone who follows the philosophy of rule utilitarianism as formulated by John Stuart Mill, would be aware of his famous Harm Principle, and might therefore argue that while companies exist to maximise profits, they must not do so in a manner that might damage the health of or cause physical injury to stakeholders, for example by neglecting health and safety standards within their premises.

A possible compromise between the concerns of shareholders and stakeholders can potentially be found in the work of Roger Steare, a ‘corporate philosopher’ in the Aristotelian tradition of virtue ethics, who trains the management of companies to be more virtuous. He cites the empirical research carried out by Jim Collins at Stanford University, which indicates that when companies are led by managers who consistently exhibit the virtues of self discipline, courage and personal humility, the companies themselves tend to be more profitable and outperform their rivals.

Furthermore, not all companies regard the maximisation of profit as their main priority. For example, so-called ‘firms of endearment’ (examples include IKEA, Honda, Costco, Timberland) try to act with a measure of integrity in their corporate activity. They have outperformed the S&P 500 (a stock market index tracking the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on exchanges in the United States) by 14 times over a period of 15 years up to 2018. During the same period so-called ‘Good To Great’ Companies (a label that alludes to the title Collins’ bestselling and influential book – examples include Walgreens, Wells Fargo, Kimberley Clark, Abbott Laboratories) did so by 6 times. Within such companies, the management are actively encouraged to exhibit the virtues cited by Collins, and to give ethical consideration to stakeholders.

In doing so, it may be worth noting that one reason for their success is that they attract a better calibre of employee, namely, those who are talented but not necessarily only in it for the money (the philosopher Peter Singer’s book The Most Good You Can Do describes many individuals embedded in senior positions in the corporate world, high-flyers who are altruistically rather than selfishly motivated).

Over in the UK, Julian Richer is a successful business owner who is keenly sensitive to stakeholder concerns. Others include Matthew Moulding, Bill Gates and Yvon Chouinard.

Is corporate social responsibility is nothing more than ‘hypocritical window-dressing’?

The fact that some companies are even prepared to employ a ‘corporate philosopher’ like Roger Steare suggests that profit-making is not incompatible with stakeholder-sensitive business ethics, and the benefits of this policy are palpably represented by the performance of the above ‘firms of endearment’, who may be cited as examples that serve to challenge the rather cynical view that companies are only motivated to convey a superficial impression that they are socially responsible.

On the other hand, the philosopher Slavoj Zizek goes much further than alleging that businesses are merely engaged in ‘hypocritical window-dressing’ , as he suggests that this kind of activity on the part of companies as a so-called ‘cure’ for the ills of capitalism only exacerbates and prolongs the illness, as capitalism is the illness.

The gist of Zizek’s argument is that by purchasing a certain product in the advanced knowledge that a proportion of the payment will contribute to a worthy cause, this can offset any feelings of guilt that a culture of consumerism might induce in those who want to feel that they are socially responsible citizens. In doing so, those of a Kantian persuasion are able to consume in the knowledge that they are fulfilling an ethical duty such as, for example, observing a maxim that requires someone to act in a manner that will benefit a fellow member of the ‘kingdom of ends’ in a poor country, Or in the case of a utilitarian, the purchase will contribute more fully to the overall happiness because a poorer person will benefit. In a similar fashion, the company selling the product can convince itself that it is meeting its wider ethical obligations. By way of illustration, Zizek mentions the footwear and accessory designer and retailer TOMS, who formerly operated a “One for One” giving strategy — that is, buy a pair of shoes and the brand gives a pair to a child in a developing or undeveloped country.

For Zizek, this is an example of ‘global capitalism with a human face’. And what this form of capitalism does is perpetuate the very problems – economic inequalities and environmental damage – that it is attempting to alleviate. For Zizek, a better aim would be to do away with capitalism altogether on order to create better societies where poverty becomes an impossibility. An example of how this could be achieved is described below – Kohei Saito’s Marxist inspired eco-socialism.

Going back to the original question, whether firms are genuine in their philanthropic activities therefore turns out to be neither here nor there for Zizek, as it is the capitalist system and the consumer society that results from it that is itself in need of a radical overhaul or perhaps replacing altogether.

Shareholders versus Stakeholders Part Two : the 2022 UK Energy Crisis

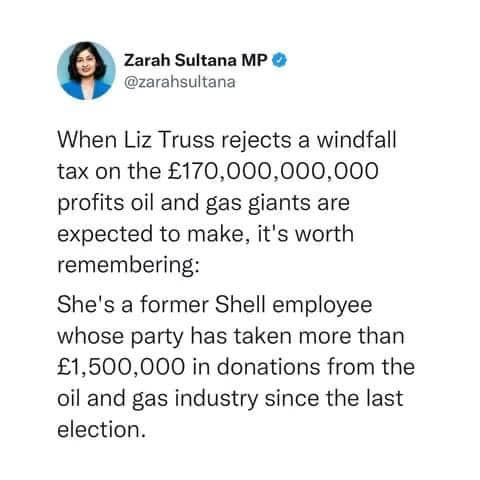

Moving on yet again, the current energy crisis, which has led to criticism of UK energy supplying companies continuing to maintain vast profits while foisting bills on their customers that are driving them into ‘fuel poverty’ is arguably a classic example of the shareholder versus stakeholder issue being played out in real time. And in this instance, it would seem that Prime Minister Elizabeth Truss is following a Milton Friedman-like trajectory. The fact that government policy and intervention (or lack of it) features in this instance should come as no surprise, as businesses often court influence over politicians and their parties and may donate to them. Politicians who leave office also often subsequently secure remunerative positions in prominent companies, who then benefit from the expertise that politician has acquired while they were in a ministerial post, as well as the connections they will continue to maintain with Westminster. Additionally, it may be not without significance that Truss herself was once employed by Shell as a management accountant.

As Sultana states, Truss has publicly declared that she is “against a windfall tax”. During a debate in parliament she said: “I believe it is the wrong thing to be putting companies off investing in the United Kingdom just when we need to be growing the economy.” So energy companies will be allowed to keep their profits. Instead, domestic energy bills will be frozen at around £2,500 annually for the typical household. It is currently unknown exactly how long the support for energy consumers will last for, but analysts have estimated the total bill for the package could reach at least £100 billion. This package would be funded by increased government borrowing and so is effectively a loan paid for by the British taxpayer.

In response, Labour party leader Sir Keir Starmer has questioned how Truss plans to raise money for her package, arguing the government should instead extend a windfall tax on gas and oil company profits to pay for the support, rather than heaping debt on taxpayers’ shoulders in years to come. Speaking at the first Prime Ministers Questions session since Ms Truss took office, the Labour leader told MPs that energy producers, “will make £170bn in excess profits over the next two years”. He added, “Is she really telling us that she is going to leave these vast excess profits on the table and make working people foot the bill for decades to come?”

As for Truss’s claim that a windfall tax may deter companies from investing in the UK, this has not prevented Germany from imposing a tax of this kind on its own energy companies.