What your Christianity syllabus says…

4.2 Secularisation (2)

- Religion in today’s society, declining numbers, the role of the Church in formal worship and in modern life and the strengths, weaknesses and impact of the teachings of popular atheists.

- The rise of New Religious Movements and definitions of ‘spiritual’ and ‘religious’.

- Disillusionment with some aspects of traditional religion compared to hard line atheism.

As you have previously learned, the term ‘secularization’ (which can be spelt with a ‘z’ or an ‘s’) is used to refer to a process in which religion/religious belief in a society gradually declines and then eventually dies out.

Is there evidence to support this theory? Is religious faith on the decline? If so, where is this happening and why? The purpose of this handout is to examine these issues.

Introduction

A slightly longer definition of secularization is that it is a process whereby religious institutions decline and religion becomes less important both for society and for the individual. Writers on secularization typically do not simply describe this process. They also try to explain why it is happening. Note that some theorists regard secularization as inevitable. They regard religion as being incompatible with the trajectory that modern societies are moving in (for various reasons that will be described below). Other theorists accept that there is a connection between secularization and modernity but do not agree that religion is incompatible with modern society. Still other theorists fundamentally question the whole idea of the secularization process, usually by appealing to evidence from the wider world that religion is still significant.

Europe/the UK

There is plenty of evidence that religion is in decline in Northern Europe as the Christian church loses its power and influence in society. In Britain, for example, church attendance halved between 1875 and 1975 and halved again over the next 25 years. According to the philosopher Jules Evans, the latest figures indicate that only 750,000 people attend Church of England services on Sundays, which is less than 2% of the population.

Taking into account Britain as a whole (and other denominations overlooked by Evans), Church attendance had declined to about 3 million by 2015, and in England, membership is forecast to decline to 2.53 million (4.3% of the population) by 2025. For more detail on this trend, see this link:

https://faithsurvey.co.uk/uk-christianity.html

Meanwhile, writing in 2003, the sociologist of religion Paul Heelas writes that, ‘In Northern Europe in particular, the decline of church attendance is relentless. Figures are down to a few per cent in countries like Sweden.’

Exam tip: note how the number 75 occurs more than once in the above figures, making them easier to memorise.

For Steve Bruce, figures like this indicate that a process of secularization is well underway in many parts of Europe. He argues that this is because religion is incompatible with modern, urban existence and is partly the consequence of a corresponding breakdown of communal, rural life in which traditionally, the Christian church used to have a bigger role. Bruce also points to the rise of individualism and rationalism as further contributing factors in this process. As he puts it:

‘[I]ndividualism threatened the communal basis of religious belief and behaviour, while rationality removed many of the purposes of religion and rendered many of its beliefs implausible.’

According to Bruce, our more pluralistic (see below for a definition of what this is), urban-based societies (that are partly a result of migration patterns in which those moving to Western Europe bring with them faiths of their own) have called into question the Christian church’s claim to be the sole repository of absolute religious truth. From its position at the heart of social life, religion therefore becomes nothing more than a highly subjective lifestyle choice in which individuals simply choose from the ‘pick and mix’ on offer.

A last, important claim that Bruce makes to support his analysis is to argue that Northern European societies like Britain lead the way in this process. What happens in the UK today will happen elsewhere tomorrow.

NOTE: this last move of Bruce’s allows him to maintain his view in the face of evidence from societies outside Northern Europe that secularization is not yet occurring. These societies are simply lagging behind ours in their cultural evolution. Note also that Bruce could, if he wanted to, appeal to the rise of the New Atheism and the popularity of authors like Dawkins, Hitchens et al. that rationality is displacing religion as the basis for modern life.

Peter Berger

Like Bruce, the American sociologist Peter Berger initially argued that the growing pluralism of modern societies – a result of urbanization and migration – undermines religious belief because it calls into question the monopoly over religious truth that religious institutions used to enjoy. The term ‘pluralism’ refers to the presence of many different faiths in a given society. For Berger, pluralism leads to competition between faiths which ultimately damages them all simply because they cannot all be true. As a consequence, religious belief itself is undermined.

However, Berger has since changed his mind about all this. In 1999 he wrote:

‘…the assumption that we live in a secularized world is false. The world today….is as furiously religious as ever [which is a good quotation to remember]… ‘secularization theory’ is essentially mistaken.’

What brought about this change?

First of all, pluralism is still a significant feature in his analysis. However, rather than seeing it as undermining belief, Berger suggests that it has changed the manner in which we believe. We now have to decide for ourselves which of the competing truth claims of religions seem most believable for us but the choice we make may still be one that we stick to. Our religious beliefs are not clung to weakly.

Additionally, Berger points to the lack of a decline in church attendance in the USA, and the rise of militant forms of Islam, Hinduism and even Buddhism in other parts of the world as further evidence that counts against the claim that religion is incompatible with modernity. Migration flows have also brought politicised religion even into the heart of Europe where, for example, Muslims (not necessarily radical ones) now constitute an important political and religious presence.

Pluralism and the rise of New Religious Movements

If secularization is not taking place on a grand scale, what is going on? In what ways are people believing differently? Here we will look at developments in societies that are perceived to be modern. This category therefore includes many parts of Europe, the USA, and Australasia.

First of all, a significant minority of people are embracing what are known as New Religious Movements (or NRM’s – a useful shorthand if you end up mentioning them in an examination answer).

While all religions are new to begin with, and the existence of new religions is not a new phenomenon, arguably it is the case that the last hundred years or so have seen an unprecedented proliferation of new religions and alternative spiritualities. One of the key changes underlying this unprecedented growth is the emergence of religiously plural societies. That is to say, increasingly societies are multicultural and multi-religious.

For various reasons, people, sometimes whole communities, have travelled from the countries in which they were born to settle in other countries and cultures. This has led to a situation in the world in which many people now live in a religiously plural society. Globalization, modern methods of travel and the internet have also increased people’s exposure to the existence of other faiths and arguably lead to a better understanding of them (though negative, popular media-driven portrayals of Islam have tended to work in the opposite way), especially given that world faiths also tend to be studied as part of the RS school curriculum.

In summary, at the beginning of the 20th Century, the majority of Westerners would have known little about non-Christian faiths. Generally speaking, this not the case today. Not only are people much more interested in and usually tolerant of the beliefs of others (with Islamaphobia perhaps making Islam the exception), in some cases they have adopted these new faiths in preference to the dominant religious beliefs in their own cultures.

It is not surprising that, within this religiously plural context, people should start not only to look away from traditional religious providers such as the Christian church, but also to experiment with a range of other faiths, including those major world faiths that are ‘new’ only in the sense that they have become better known in the West over the last century.

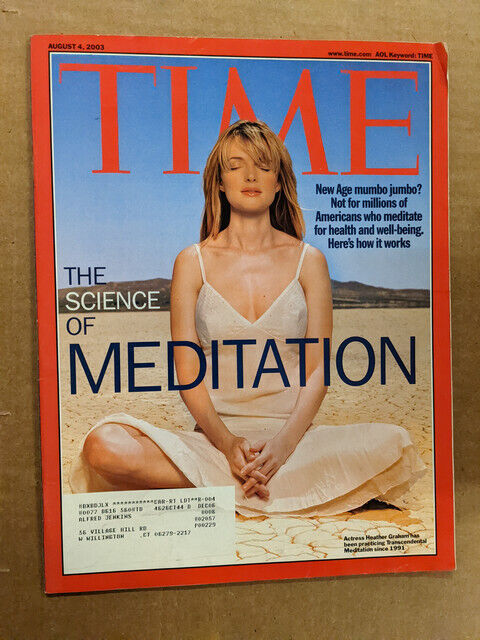

Additionally, the term ‘New Religious Movements’ can also be applied to developments within an already established tradition. Examples might include ISIS (Islam), the Hare Krishna movement* and Transcendental Meditation (Hinduism), the Mormons/Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and the Jehovah’s Witnesses (Christianity), modern Kaballah (Judaism), and the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order or FWBO (Buddhism).

In the Simpsons episode ‘She of Little Faith’, Lisa temporarily converts to Tibetan Buddhism with the help of actor Richard Gere

Still other modern and fairly well-known NRM’s have arisen in other ways. For example, the Church of Scientology evolved out of an unusual form of psychotherapy called Dianetics, while Paganism (which at one point was regularly reported as being Britain’s fastest growing religious tradition) has its roots in the pre-Christian world view that preceded the spread of Christianity to the UK.

*more formally known as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness or ISKCON.

Religion and Spirituality

The rise of modern NRM’s has also been accompanied by an increased interest in what can be described as ‘alternative spirituality’. Before exploring what this entails, let’s quickly distinguish between the terms ‘religious’ and ‘spiritual’.

The term ‘religious’ may refer to experiences which confirm or conform to the beliefs and practices of an established religious tradition and that may arise in the course of religious observance or are the result of lengthy preparation and devotion e.g. time spent in fasting, meditation or prayer. Such experiences may be communal or solitary.

‘Spiritual’ is a more general term which may not be reflective of any mainstream or specific religious beliefs and may experientially describe an awareness of some higher dimension or power that is not explicable in a down-to-earth way.

One of the things that has arguably developed alongside the increased emphasis on individualism in modern society has been the emergence of personally and privately held non-institutional forms of belief and practice. The sacred persists, but increasingly it does so in non-traditional forms. There is, as the sociologist Grace Davie has noted, ‘believing without belonging’. This ‘believing without belonging’ could be described as being ‘spiritual’ rather than religious. There is in the West, for example, a move away from beliefs that have developed within traditional Christian institutions towards forms of belief that focus primarily on the self, on nature, or simply on life itself. As noted by Paul Heelas, one example of this is the New Age movement, which embraces a wide variety of alternative therapies, practices and outlooks based on what he refers to as the sacralization of the self.

Alongside this development is a growing suspicion of traditional religious authority, sacred texts, churches, and hierarchies of power. There is a move away from a ‘religion’ that focuses on things that are considered to be external to the self (god, the Bible, the Church) to ‘spirituality’, that which focuses on the self and is more personal and interior. Of course, spirituality is a part of the major faith traditions too. For example, mystical experience is one aspect of this. But while those who have pursued alternative forms of spirituality might be inspired by mystical writings, such sources may not be regarded as being authoritative in the manner in which scripture is regarded as authoritative in, say, Christianity and Islam.

In pursuit of an alternative spirituality the seeker might also mix and match, taking inspiration from the more mystical sayings of Jesus, or Taoist ideas. Whatever they get up to, such individuals will generally follow a personally tailored path that focuses primarily on the self and that can therefore be distinguished from what would usually be regarded as ‘religion’.

Perhaps spirituality can therefore be understood as a path which, though it is preoccupied with the self, seeks to embrace all life and to move beyond the boundaries of formal, institutional religion. However, it is also important to add that while some would argue that institutional religion can stifle true spirituality, that many members of traditional faiths would understand the spiritual dimension to be at the heart of all true religion.

NOTE: for some prominent evangelical Christians, the popularity of NRMs is taken as evidence for what they regard as the ongoing battle between God and Satan. For example, writing about the loose amalgam of self-directed meditation practices, human potential movements and miscellaneous spiritualities that fall under the broad category of the New Age Movement, Douglas Groothuis has declared that, ‘…whatever good intentions New Agers may have, it is Satan…who inspires all false religion.’ This is a point to bear in mind when you study Evangelicalism, Pentecostalism and Charismatic Christianity, as it is from this territory that this type of criticism has emerged.

‘Disillusionment with some aspects of traditional religion compared to hard line atheism’

All this is evidence that many people are not necessarily turning to hardline atheism, even allowing for the previously noted popularity of the publications of the four horsemen of New Atheism.

Although Heelas wrote the following back in 2003, before the New Atheists came to prominence, and the New Age movement has declined in importance since, his comments are still relevant:

‘ …the fact that fewer people are going to church does not mean…that Britain is becoming a nation of atheists. Far from it: for a very great deal is going on ‘beyond’ church and chapel. Whether it be yoga or astrology in popular culture, belief among the general population in a ‘God within’….there is plenty for the sociologist of religion to study. Indeed, the ‘sacred’ is showing distinct signs of vibrancy, with ‘spirituality’, for example, making inroads with regard to well-being culture, education, business and health.’

One example of what Heelas might be referring to here is the growing popularity of ‘Mindfulness’, a Buddhist meditative practice that is becoming popular in the workplace and in some schools (to alleviate examination nerves and stress), as well as having had its efficacy confirmed in the UK by NICE (the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). Another might be the rise of the modern business ‘guru’, who themselves have been influenced by NRM’s and spiritual philosophies.

But why the disillusionment with traditional religion? There could be several reasons for this.

- Apparently, many women who have left Christianity for modern Paganism have said that it fits them better emotionally and intellectually, particularly with its emphasis on eco-spirituality and the valuation of nature, witchcraft, Goddess based spirituality, and the perception of sexuality as a positive, life affirming force. By comparison, Christianity may be seen as a faith which has typically encouraged a negative, guilt-driven, repressive view of both sex and sexuality, especially that of homosexuals and lesbians, even allowing for the recent acceptance of same-sex marriage by some Christian denominations. Sex has also been regarded as sinful outside the traditional confines of a marital relationship. Additionally, Christianity has also arguably traditionally accorded women inferior status, in spite of recent progress that has been made in this respect with regard to the appointment of women priests and bishops in the Anglican tradition.

- Many people today have experienced problems reconciling theistic faith with the problem of evil and with scientific accounts of human origins that they see as obviating the need for faith in God. But rather than embracing hardline atheism, an alternative is to turn to the non-theistic tradition of Buddhism. Typically, Buddhism rejects the idea of there being a creator God possessing the qualities that classical theism ascribes to Him. Various types of Buddhist meditation also hold out the possibility of personal transformation. This therefore might account for the rising popularity of various Buddhist traditions and practices in the West.

- The rise of celebrity culture may also have increased the appeal of NRM’s and alternative spirituality at the expense of traditional Christianity. According to Douglas Cowan, celebrity culture can encourage something he calls ‘emulative conversion’. This phrase describes a process in which people emulate the religious beliefs and practices of celebrities with whom they identify. That is, many might become interested in a new religion as a result of being presented with a pop culture product – a film, say, or TV series that presents religion in a positive light or because a celebrity happens to be a prominent member of an NRM. As examples, Cowan cites the interest in Scientology resulting from Tom Cruise’s adherence to the faith, and the popularity of series like Charmed and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which feature powerful female characters in lead roles that provide modern Paganism with a measure of social support. Other, less recent examples include Beatle George Harrison’s involvement with the Hare Krishna movement, the interest in Tibetan Buddhism generated by actor Richard Gere, and Madonna’s interest in Kaballah.

Conclusion

In the 1960’s and early 1970’s, popular wisdom insisted that the technological and scientific advances of late modern society, along with an accompanying emphasis on rationality, were inevitably displacing religion as the dominant force in human life. The ‘God hypothesis’ as advocated within Christianity was no longer needed to explain the world, and it was believed that eventually, all that would remain of religion would be a rapidly fading echo of a less enlightened past. Judging by the decline of mainstream church attendance in Northern Europe, this theory of gradual secularization seemed reasonable.

However, three things could be said to be wrong with it. First, it overlooked the wider religious world beyond those European churches, the Muslim and Hindu worlds, for example, which saw no such decline in the same period. Secondly, it failed to acknowledge the growth of evangelical, charismatic and pentecostal churches in the USA and elsewhere. Thirdly, it did not take account of the eruption of New Religious Movements and alternative forms of spirituality. In reality, people are not necessarily embracing secularism as New Atheists would prefer them to and becoming less religious. Instead they seem to be coming differently religious, with an emphasis on self-exploration and a quest for meaningful spiritual experiences.

Having said this, at the popular level authors like Richard Dawkins have helped to forge a distinctive identity for atheists that may be reflected to a degree in the rise of people describing themselves as ‘nones’ (individuals who choose the option ‘No religion’ in response to survey questions about religious affiliation). This is evidence for a degree of secularization at the individual level, in the UK at least. However, the bigger picture is more complex and suggests that the impact that popular atheists have had may not be as significant as many have assumed.