Pleasantville is a movie which looks at evil and suffering from an Irenaean point of view. Irenaeus thought that the evil things that happen to us are not a punishment from God, as Augustine believed, but should be seen as challenges that are meant to shape and improve our personality. This blog entry will re-examine the Irenaean theodicy and also take a look at Buddhist teaching about suffering.

The Plot

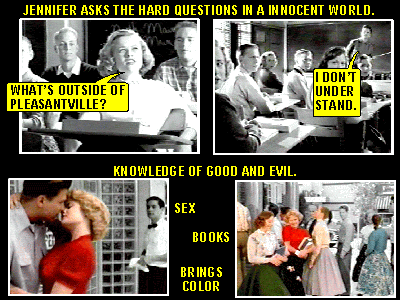

David and Jennifer are siblings who attend the same high school. At the start of the movie, through their classes, we get introduced to various examples of natural and moral evil, like global warming and famine. We also see that their mother and father have separated and that their own relationship is similarly fractious. For example, David is nerdish and academic, someone who prefers to flee from reality by immersing himself in a 1950’s TV sitcom called Pleasantville, one that presents him with an Edenic, paradisiacal town where family and community life is idyllic and there is a total absence of evil. Contrastingly, Jennifer is a precociously amatory character who maintains a predatory interest in boys and appears to have no interest in or aptitude for study.

One evening, when both are at home alone, they fight over access to the TV remote control. Jennifer wishes to see a concert on MTV with a hot date that is coming over, but David wants to watch an all-night marathon of his favourite show, and take part in a phone-in trivia contest that holds out the prospect of a substantial cash prize. In their struggle with the remote, they accidentally break it.

Almost immediately, a television repairman rings their doorbell offering them help. The teens are confused about how the repairman knew they needed assistance, but are rewarded with a new and odd looking remote, after David exhibits an uncannily impressive knowledge of the series to him. The repairman insists that this device will put the teenagers ‘right in the show’. While once again wrestling for control of it, they are abruptly transported into the television and the black and white world of Pleasantville, suddenly dressed as the sibling characters Bud and Mary Sue.

Without giving too much of what subsequently ensues away, they quickly discover that they are in a logically impossible world, one with a non-linear geography, and where, among other things, fire does not burn, and the high school basketball team defy the natural law of gravity in their training sessions.

Pleasantville and Theodicy

Not only did the philosopher Gottfied Leibniz (1646 – 1716) coin the term ‘theodicy’ (an explanation of why a perfectly good, almighty, and all-knowing God permits evil), he is also famous for insisting that ‘we live in the best of all possible worlds.’ Given that Pleasantville presents us with the possibility of a world with no natural or moral evil, does this not demonstrate that he was wrong about this? Furthermore, In the above clip, the late Ninian Smart states that the Divine Being is supposed to confer freedom on us, and that freedom requires the universe to be ‘orderly’. But Pleasantville is undoubtedly orderly too. So why didn’t God create a world like it instead of one with global warming, famine, divorce and family strife, the world of Bud and Mary Sue rather than that of David and Jennifer?

In reply, some theologians have said that even an omnipotent God can only do things that are logically possible. For example, He cannot make a square circle, or a rock so heavy that he is unable to lift it. It is therefore possible that the movie Pleasantville is trying to point this out. The town is one that God could not create, even if He was all-powerful. So instead, the next best thing He could make was a world like the one we are in now, where there just has to be some evil.

The free-will defence

When it came to creating us, a significant number of those aforementioned theologians additionally contend that God was faced with a choice: on the one hand He could have made us like the citizens of Pleasantville. If He had done that, we would then be like the character Skip Walker (see the above scene), who merely imagines that he is making decisions, but in fact is in thrall to a script. People who believe in God think that it would have been pointless to make us like this as we would no longer be human. To be properly human, we have to be free to make real choices for ourselves. So that’s what God did. He made us like David and Jennifer are in the real world, rather than the people in Pleasantville. But because of this, if we use our freedom to make bad choices and do things that count as moral evil, then that is our responsibility. We cannot blame God for this. This line of thought is known as ‘the free-will defence’.

J.L. Mackie : ‘Evil and Omnipotence’

However, the sceptical philosopher J.L. Mackie contends that God was not faced with a binary choice. A third option was open to Him:

‘If there is no logical impossibility in a man’s freely choosing the good on one, or several occasions, there cannot be a logical impossibility in his freely choosing the good on every occasion. God was not, then, faced with a choice between making innocent automata and making beings who, in acting freely, would sometimes go wrong; there was open to him the obviously better possibility of making beings who would act freely but always go right. Clearly, his failure to avail himself of this possibility is inconsistent with him being both omnipotent and wholly good.’

Mackie’s point appears to be well-made. For example, if a student goes through an inner struggle on one occasion when they are required to produce a piece of homework for their Religious Studies teacher, but end up reluctantly completing the task when they would much rather have been doing something else, then they may be thought of as having made a free choice which will hopefully meet with the approval of that teacher. Even though they could be under pressure to succeed academically from their parents and educators, and may face a disciplinary sanction if they do not hand in their essay on time, at the end of the day they are not being forced to do so. And yet they did the right thing of their own volition. Mackie’s point is that God could have designed us to do the right thing on each and every occasion, not just one, to always do our homework in other words.

In response to Mackie, it has been suggested that his third scenario does not constitute a genuine form of freedom, for we are still effectively God’s puppets. As John Hick has written, ‘Such “freedom” would be comparable to that of patients acting out a series of posthypnotic suggestions [or, one might add, TV characters acting from a script without being aware of doing so]: they appear to themselves to be free, but their volitions have actually been predetermined by the will of the hypnotist. Thus, it is suggested, while God could have created such beings, there would have been no point in doing so.’

Assuming that there is also a prior inner struggle on the part of those who nevertheless always go on to do the right thing, their actions could still be said to be not freely chosen because there is no real opportunity to make immoral decisions, to follow through and act on their worst impulses. Plus, as Richard Swinburne has pointed out, God did not make a ‘toy world’ in which our free choices do not really matter, because such a place would not be truly meaningful. Instead, a world where we have a genuine opportunity to inflict real harm on others is the only one that makes any sense as far as our moral decisions are concerned, which also give us an opportunity to damn ourselves through what we do. Swinburne’s ‘toy world’ is, perhaps, echoed in the blandness and insubstantiality of the black and white setting of Pleasantville, where everything is unfailingly agreeable, but also arguably inconsequential.

Soul-Making (NOTE: THERE ARE SIGNIFICANT SPOILERS IN THIS SECTION)

According to Irenaeus (c. 130-c.200 AD), Adam and Eve should be thought of, not as fully accountable human beings who introduced original sin into the world, but more as morally and spiritually immature creatures who carelessly disobeyed a simple rule. He therefore regarded the world of God’s creation as one which provides opportunities to learn from our mistakes, to grow and develop through a process of what has been called ‘soul-making’. Unlike Augustine, for whom all evil is a punishment, the Irenaean theodicy sees all evil as having a purpose. It is meant to challenge us to make the right choices that assist our moral and spiritual growth.

Pleasantville too is a place where many of the characters undergo a process akin to ‘soul-making’, which takes place when they change from black and white to colour. For many citizens of the town, this happens when they discover their own sexuality. But for others, the transition occurs when hitherto unexplored aspects of their inner selves are brought to light. For example, Bill Johnson, the owner of the local soda shop, is transformed when he taps into and then begins to express a previously repressed artistic imagination, Mary Sue morphs as a consequence of an encounter with literature and study, Bud finally changes when he learns to become more assertive, and George Parker does so when he simply realizes the profound depth of his love for his wife . However, what is revealed is not always easy to accept. For example, local grandee Big Bob is forced to confront the depths of his own anger and intolerance, when a mirror is literally held up to it. Interestingly, the accompanying landscape of Pleasantville also becomes slowly transmogrified, with the appearance of fire, rain and thunder, all with the potential – as forms of natural evil – to be hazards as well as beneficial.

Interestingly, the fact that sex is frequently a catalyst for change has attracted criticism of the movie from conservative Christians, who have expressed disapproval of much of its content. For example, here is a sample of comments found on the website Christian Answers :

‘Pleasantville is not so Pleasant. I walked out of the movie theater very confused and disappointed. Sin was portrayed as colorful and interesting. This is exactly what Satan wanted Adam and Eve to think (i.e. the “apple” scene). I was offended by the language. I was also shocked and embarrassed at the sexual scenes and the masturbation scene. I could not recommend this movie, even though the special effects were superb.’

‘Hate speech against God’s word, is nothing new. This recent movie is chocked full of lies, distortions, and role reversals where good is evil and evil is good. Of course good is completely slandered and falsely represented. Pleasantville is a twisted allegory of Genesis with so much nonsense, Sunday school third graders could see through the holes of absurdity. ‘

However, not all the viewer comments are negative:

‘It seems as though self proclaimed “Christians” commenting on the “immorality” of this fine movie make exactly the point this movie emphasizes. The “good ole days” were not all good. The security enjoyed by many were not enjoyed by all. “Coloured” people in the “good ole” 50’s were strung up and forced to live a life less than that of the rest of their fellow citizens. Dark family secrets were just that—secrets. Sex—the embodiment of love between two people was not spoken of. Fear, not morality, was the guiding light…’

In fact, the movie does indeed allude to the Genesis narrative, with David and Jennifer functioning as cyphers for Adam and Eve to an extent (but only to an extent, given that they are brother and sister), while the TV repairman represents God. And at Lover’s Lane, Bud’s girlfriend re-enacts the plucking of an apple from a tree, with the aforementioned repairman drawing Bud’s attention to this misdeed. As for sexuality, Jennifer introduces this into the town through her seduction of Skip, which perhaps is a further allusion to the fact that sex is the means through which Original Sin is transmitted.

To sum up, the film’s detractors appear to overlook the fact that it can also be regarded as an experiment in theodicy, and in particular, a cinematic exploration of the Irenaean theodicy, and therefore is only indulging in the gentle mockery of Christian fundamentalism.

Buddhism and Pleasantville (MORE SPOILERS HERE)

At the very end of Pleasantville, with David having returned to the real world, he has a brief conversation with his mother that is also of significance when it comes to the contemplation of evil and suffering, one which unfolds as follows:

David’s Mom: When your father was here, I used to think, “This was it.” This is the way it was always going to be. I had the right house. I had the right car. I had the right life.

David: There is no right house. There is no right car.

David’s Mom: God, my face must be a mess.

David: It looks great.

David’s Mom: Honey, it’s really sweet of you, but I’m sure it does not look “great.”

David: Sure it does. Come here.

David’s Mom: I‘m 40 years old. I mean, it’s not supposed to be like this.

David: It’s not supposed to be anything. Hold still.

David’s Mom: How‘d you get so smart all of a sudden?

David: [pause]: I had a good day.

For Buddhists, there is no problem of evil, only a problem of suffering or dukkha, as stated in the first of what are known as the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism, as taught by the historical Buddha Siddhartha Gautama as part of his famous Deer Park Sermon back in the sixth century BC. This is because Buddhists do not believe that there is one, Creator God. They are not monotheists. Although the Buddhist scriptures mention gods, there are many of them and they die and get reborn too. Like Hindus, Buddhists also believe in karma and rebirth, and that liberation is possible through good intentions (rather than actions), and meditation. But unlike Hindus, Buddhists do not believe that they become one with Brahman (the impersonal ultimate reality underlying all phenomena in the Hindu scriptures). Instead, doing a lot of meditation helps to free people from suffering and leads on to the attainment of a state called Nirvana. Here, the term dukkha only refers to the physical and psychological suffering that living beings inevitably experience as a consequence of being alive. Contrastingly, natural evil is regarded as part of the fabric of the universe, something that does not require any further explanation.

The full text of the Deer Park Sermon reads as follows:

The Noble Truth of Suffering (Dukkha), monks, is this: Birth is suffering, ageing is suffering, sickness is suffering, death is suffering, association with the unpleasant is suffering, dissociation from the pleasant is suffering, not to receive what one desires is suffering – in brief the five aggregates subject to grasping are suffering.

The Noble Truth of the Origin (cause) of Suffering is this: It is this craving (thirst) which produces re-becoming (rebirth) accompanied by passionate greed, and finding fresh delight now here, and now there, namely craving for sense pleasure, craving for existence and craving for non-existence (self-annihilation).

The Noble Truth of the Cessation of Suffering is this: It is the complete cessation of that very craving, giving it up, relinquishing it, liberating oneself from it, and detaching oneself from it.

The Noble Truth of the Path Leading to the Cessation of Suffering is this: It is the Noble Eightfold Path, and nothing else, namely: right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration.

It is beyond the scope of this blog entry to discuss the entire content of the sermon, but the Zen Buddhist teacher Brad Warner has helpfully discussed the essence of dukkha (which he prefers to translate as ‘unsatisfactory experience’) in a straightforward manner that can easily be related to David’s conversation with his mother:

“The first noble truth, suffering, represents idealism. When you look at things from an idealistic viewpoint everything sucks, as the Descendents said in the song called “Everything Sucks” (from the album Everything Sucks). Nothing can possibly live up to the ideals and fantasies you’ve created. So we suffer because things are not the way we think they ought to be. Rather than face what really is, we prefer to retreat and compare what we’re living through with the way we think it oughta be. Suffering comes from the comparison between the two.”

So in craving for the ‘right’ house, car and life, David’s mother is clearly illustrating what the Buddha wished to teach: we suffer whenever we wish things to be different than they are.

Warner continues:

‘Even physical suffering works like this. I saw this fact clearly for myself about a year ago when I passed a kidney stone, allegedly the most painful experience a person can actually survive. I don’t know about that but I can tell you that the pain was astoundingly bad. And yet when I stopped comparing what I thought I ought to feel like (namely, free from pain) to what I actually felt like (namely, in enormous pain), things became far better. It still hurt like hell, don’t get me wrong. But if you’re not trying to run away from the unavoidable hell of suffering, if you just let it be, your whole experience is transformed absolutely.’

Concluding Comments

Swinburne’s “toy world” thesis is undoubtedly controversial, as he has even gone so far as to say that that the existence of Nazi concentration camps can be justified if some good came out of this terrible episode in history, such as acts of sympathy, co-operation and compassion. For others, the price to be paid for having acquired an ability to misuse our free-will in a non-artificial setting is too steep.

For example, critics of the Irenaean theodicy have suggested that a good deal of evil seems to have no purpose or point to it. An example of pointless evil might be all the animal suffering that went on before human beings evolved, or all the suffering that is going on now in the animal kingdom which we are unaware of because we are not there to observe it (e.g. a lion hunting down and killing a zebra away from any human eyewitnesses). This purposeless suffering also extends to humans. For example, cruelty to children has sometimes been mentioned as an example of this to make the point that the cost in terms of human suffering is too high to make any ‘vale of soul-making’ worthwhile. For example, the Russian novelist Dostoevsky thought that there was no goal worth having that involved any kind of child torture along the way.

With respect to Buddhism and the acceptance of ‘unsatisfactory experience’, perhaps this teaching demands too much of us. For instance, would this still be possible in Auschwitz, or in other, comparably appalling situations that some people find themselves in?

Overall then, the Irenaean theodicy and Buddhist teaching about the relationship between suffering and craving are not going to resonate with everyone. Nevertheless, to the extent that the movie Pleasantville serves as an illustration of both these perspectives, it provides intriguing food for thought.