From the 4B Christianity syllabus:

| New movements in theology The context and key themes of Liberation theology, Feminist theology and Black theology. The development of these ideas and their impact on the lives of believers and communities in Christianity today. With reference to the ideas of G Gutiérrez, S McFague and J H Cone. |

Liberation Theology

‘Liberation Theology’ is the name given to a movement that emerged in Latin America in the 1960’s that was led by Roman Catholic priests, churches and theologians. In 1968, at a conference of Roman Catholic bishops from Latin America held in Columbia, some members insisted that the starting point for theological reflection must be the situation of the poor. Academic theologians in the earlier part of the century had not said much about poverty, apart from being against it, and the recent papal encyclicals that had resulted from Vatican II had highlighted the widening gap between rich and poor. Now that the membership of the Catholic Church was increasing in Latin American countries, it was felt that it was no longer acceptable to take poverty for granted. The whole system that was producing this poverty had to be challenged through direct action. This emphasis on linking theology with action by actually doing something about the situation of the poor (the important term ‘Praxis’ in Liberation Theology refers to this approach), echoes the famous quotation from Marx above who was famously critical of the capitalist economic system that he regarded as being inherently oppressive.

Adam Smith and free-market capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system whereby the means of production [factories, machinery and so on] and distribution are owned primarily by private individuals and corporations. The prices of labour and goods are determined by the free market and not by central government. Profits are claimed by individual company owners or, in the case of corporations, by shareholders. This form of economic theory has been the dominant one over the last thirty years but dates back to the 18th Century and the writing of the Scottish moral philosopher and economist Adam Smith who argued that if left alone competitive markets will naturally produce stability and prosperity. Businesses should therefore be given maximum freedom. Firms, being closest to the market know what is best for their businesses.

In a nutshell: the rapidly adjusting market ensures balance, stability and prosperity.

However, free-market policies have – according to critics of this approach – resulted in slower growth, rising inequality and heightened instability in most countries, especially in poorer regions containing LEDC’s like Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

Karl Marx and Socialism

Marx was the most famous critic of capitalist theory. According to Marx, capitalism requires profit and profit requires exploitation (of employees and, perhaps, to update Marxism for the 21st Century, the environment). Marx thought that morality was a disguise for class interests that led to the kind of exploitation previously mentioned.

He therefore proposed socialism as an alternative economic theory. This is an economic system whereby the means of production and distribution are owned by the workers and the state. The prices of goods and wages are fixed by central government instead of being regulated by the market. The whole economy is rationally planned, rather than being determined by the random outcome of private initiatives.

In a nutshell: Capitalism requires profit and profit requires exploitation.

NOTE: Marx argued that capitalism inevitably produces revolution: eventually, people at the bottom of the class system become so intolerably exploited that they rise up against their masters and seize the means of production. The subsequent Communist society would then be a utopia in which its members would be spontaneously moral, as all immoral behaviour was held to be a product of class oppression. Here, there are echoes of the Christian eschatological view that a Kingdom of God will eventually be established after a period of strife and chaos in which the forces of evil are eventually defeated.

Gustavo Gutierrez

Gustavo Gutiérrez (born 8 June 1928) is a Peruvian philosopher, theologian, and Dominican priest regarded as one of the founders of liberation theology.Gutierrez’s work A Theology of Liberation is the most famous and influential book on Liberation Theology. In it, the following arguments are set out (which can be taken as representative of Liberation Theology generally, even though the relevant theologians do not all think the same way):

- There must be ‘a preferential option for the poor’. In other words, proper Christian theology should be based on the experiences of the poorest and most wretched in society. It should not be merely abstract and dispensed from ‘on-high’ by specialists writing from a purely academic point of view. This is a statement of what is known as contextual theology, theology that arises from the life experiences of people living in a particular time and place.

- Theology should also not be politically passive. It was not sufficient for the Catholic Church to remain neutral by saying nothing critical about the governments and capitalist systems that were responsible for creating and perpetuating economic inequality. NOTE: a Marxist analysis of the class system that produces inequality would also be ‘bottom up’ rather than ‘top down’.

- The justification for this approach to doing Theology is Biblical. Liberation Theology actually takes its name from a passage in Luke’s gospel in which Jesus refers to the book of Isaiah and the requirement – as part of his teaching – to ‘liberate those who are oppressed’. The Parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew 25, in which Jesus specifically identifies himself with the poor (‘I was hungry and you fed me, thirsty and you gave me something to drink’) is another popular passage as the Parable suggests that we are ultimately judged more than anything else on what we do for the most disadvantaged members of our society. Finally, the Exodus narrative chronicling the liberation of the Jews from slavery in Egypt provides a further important reference point that again demonstrates that God is on the side of the poor.

- Marxist methods of analysis are valid in order to identify the obstacles that have to be overcome in order to liberate the oppressed.

- Liberation, according to Gutierrez, is therefore required in three different areas. Firstly, there is a need for the poor to be freed from the social economic and political oppression that creates poverty and dependence. Secondly, the oppressed need to be liberated from all historical forces that obstruct their freedom so that they can become responsible for their own destiny and live in solidarity. Thirdly, there must ultimately be liberation from sin, as sin is at the heart of all injustice.

- Salvation is not just something that is gained in the afterlife. The Exodus story shows that God is interested in saving people from misery and oppression while they are in this world too.

The impact of Liberation Theology plus criticisms of Liberation Theology

The establishment of Christian Base Communities in Latin America by supporters of Liberation Theology has arguably been significant. A Christian Base Community is a group of people who join together to study the Bible in the light of their own situation of poverty and then take action on the basis of this social justice oriented form of Christianity. At this level, Liberation Theology has therefore inspired those participating in these communities to protest against human rights violations, to promote land reform and to campaign for the rights of peasants. These are specific examples of praxis at work (see above).

Liberation Theological perspectives have spread to and are now being articulated in other parts of the world e.g. India, Sri Lanka and the Philippines.

Black Theology and Feminist Theology have also come to prominence and have influenced and been influenced by Liberation Theology.

Óscar Romero(15 August 1917 – 24 March 1980) was the fourth Archbishop of El Salvador. He spoke out against poverty, social injustice, assassinations, and torture. In 1980, Romero was himself assassinated while offering Mass in the chapel of the Hospital of Divine Providence. Although the Catholic Church hierarchy has often been critical of Liberation Theology for the emphasis that it places on Marxism, Romero was declared a martyr by Pope Francis (who is Latin American and was born in Argentina) on 3 February 2015. Pope Francis also asked Gutierrez to be a keynote speaker at a Vatican event in 2015.

Pope Francis has also condemned ‘the idolatry of money’ (a reference to the second commandment – ‘You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above or that is on the earth beneath’). Commenting on rising inequality in many societies – the gap that exists between the rich and the poor – he has also criticised the policy followed by many governments of not interfering with the way that businesses operate. This has led Rush Limbaugh, America’s most famous radio talk-show host, to accuse Pope Francis of ‘pure Marxism.’

However, Cardinal Ratzinger (someone who also eventually became Pope Benedict) is one of many critics of Liberation Theology. He argued that its foregrounding of and insufficiently critical use of Marxist concepts was dangerous.

Many priests took off their dog collars and took up arms in the struggle against military dictatorships in Latin America in the 60’s and 70’s e.g. Camilo Torres. This violent approach is arguably at odds with the alleged pacifism of Jesus.

Concern has also been expressed that Liberation Theology has reduced the Christian faith to politics. Christianity is arguably much more than a political movement as it focuses on the well-being of the whole person, not just their physical needs.

Although Liberation Theology has not resulted in socialist governments becoming firmly established throughout Latin America, the movement has arguably drawn attention to the deficiencies of capitalism, a point which is relevant to everyone living after the 2008 financial crash in the age of austerity, especially now that capitalism is frequently presented as the only viable economic system, and given that Marxism has lost so much credibility in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the dilution of Communism in China. In the present world, supporters of Liberation Theology might even therefore be regarded as lone voices crying out in the wilderness.

Background

Between 1517 and 1840 it is estimated that twenty million Africans were captured, transported to America, and brutally enslaved. The experience of these slaves — and their descendants — serves as a backdrop for understanding the modern movement known as Black Liberation Theology, or simply Black Theology.

During the slave trading days, black Africans were crammed into ships like sardines into a can and brought across the Atlantic. Many died at sea from disease while some starved themselves to death refusing to eat. To prevent this form of suicide, hot coals were applied to the lips to force the slaves to open their mouths to eat. Upon arriving on American shores, the slaves — men, women, and children — were forced to work from sunrise to sunset. Even old and sick slaves were made to do this.

The brutality shown to the slaves was extraordinary. Black theologian Anthony Evans states that “black women were raped at will by their masters at the threat of death while their husbands could only look on. Families were separated as they were bought and sold like cattle.” For tax purposes, slaves were counted as property — like animals.

Christianity and slavery

Initially, there was resistance to spreading the Christian message among slaves. One of the reasons for this was because it was believed that black people did not have souls. However, missionary work eventually began among the slaves in the early 1700s and many of them became Christians. But the brand of Christianity that was preached to them was one that justified slavery. It was argued that St Paul and other Biblical writers issued specific instructions for master-slave relations, thus apparently signifying their approval of the practice.

Most black converts accepted the slave brand of Christianity. Plus, white missionaries persuaded them that life on earth was not that important because “obedient servants of God could expect a reward in heaven after death.” This white interpretation of Christianity therefore deprived the slaves of any concern they might have had about their lack of freedom.

By the mid-1700s, black slaves had begun meeting in private to worship since proper worship with whites was impossible. In the meetings, God was understood by the slaves to be like a loving Father who would eventually deliver them from slavery just as He had delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt in the story of Moses. Jesus was considered both a Saviour and a fellow sufferer.

‘Heaven’ had two meanings for black slaves. First of all, it referred to the afterlife. But it also came to refer to working to be free in the present. Because of the risk involved in preaching liberation, the slave learned how to sing about liberation in the very presence of the slave masters.

“Swing low, sweet chariot (= the conestoga wagon, a large wagon used for long-distance travel) Coming for to carry me home (up North to freedom) Swing low (come close to where I am), Sweet chariot, Coming for to carry me home. I looked over Jordan (= the Ohio River — the border between North and South of the USA) And what did I see, Coming for to carry me home? A band of angels (= northern freedom fighters with the underground) coming after me. Coming for to carry me home.”

What is Black Theology?

The phrase ‘Black Theology’ actually describes a movement that concerns itself with ensuring that the realities of the black experience are represented at the theological level. It became especially significant in the United States during the 1960’s and 70’s but the scope of its influence has extended to Africa and the Caribbean.

The first significant publication within the movement was Joseph Washington’s Black Religion. Dating from 1964, Washington’s book emphasized the need for the integration and assimilation of black theological insights into mainstream Protestantism. However, although this dovetailed with the racial integration that had been assumed by Martin Luther King and others to be the goal of the struggle for civil rights, alternative inspiration for Black Theology was provided by Malcolm X and the advent of the ‘Black Power’ movement.

This new religion should not be confused with the world religion of Islam which was started by Prophet Muhammad in the 6th Century in what is now modern Saudi Arabia.

It was founded in 1930 in Detroit in the USA by Wallace Fard who claimed to include Prophet Muhammad in his family tree and taught that all black Americans were the descendants of Muslims. Later, the movement was taken over and led by a man called Elijah Muhammad. Malcolm X was a spokesman for the movement and Muhammad Ali was, for a time, its most famous member.

In the 1960’s when Martin Luther King was campaigning for Black Civil Rights and racial integration, the Nation of Islam wanted to achieve freedom for black people by creating a separate black nation for them to live in where they would rule themselves and not have to experience racism.

Malcolm X argued that for far too long, white people had taken freedom and riches for themselves, leaving black people in poverty and slavery. Christianity had also failed black people by making things even worse. Or as Malcolm X put it:

‘This white man’s Christian religion further deceived and brainwashed this ‘Negro’ to turn the other cheek…and be humble, and to sing, and to pray, and take whatever was dished out by the devilish white man.’

Note the implied criticism of both Christianity and the use of non-violent tactics in this brief quotation. First of all, it is being suggested that the Christian faith is exclusively for white people. Black Christians must therefore have been ‘deceived’ into converting to it. By extension, they have also become passive as a result of adopting the pacifistic teachings of Jesus (e.g. ‘love your enemies’) that were used by Martin Luther King Jr to justify a non-violent approach to the pursuit of civil rights. These assertions may seem rather strident but have to be understood in the light of the section on Christianity and slavery above.

Furthermore, according to Black Muslim teaching, black people were the original inhabitants of the earth and founded the holy city of Mecca many thousands of years ago. In time, an evil black scientist named Yacub rebelled against Allah and set up a genetics laboratory on the island of Patmos in Greece, 6000 years ago. On Patmos, Yacub successfully bred from his black followers a bleached race of devils – the white man. Eventually, the white race spread to the mainland and made an earthly paradise a living hell for black people. But with the birth of Fard Muhammad, a new black messiah had arrived, ‘God in person’, who would set up and lead a separate Black Islamic country.

Malcolm X also argued that violence might be necessary in self-defence to help Black Muslims create a separate country for themselves, and contrasted his approach with the non-violent methods of Martin Luther King, who wanted to change America so that everyone could have equal opportunities and rights.

Eventually, Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam. After visiting Mecca on Hajj (the Muslim pilgrimage) he converted to Islam because he realized that white and black people could live together as Muslims and that the Nation of Islam’s account of racial origins was false. Two years later he was shot and killed. The murderers were followers of Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad Ali also eventually converted to Islam.

Black Power

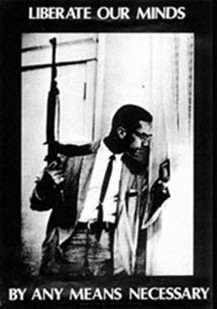

The slogan and philosophy of ‘Black Power’ came to prominence after two black activists, Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton published a book with the same title which argued that blacks must work together to achieve their cultural, economic and political liberation. They called for the black people of the United States ‘to unite, to recognise their heritage, to build a sensed community….to define their own goals, to lead their own organisations.’ Their approach was militant (‘When you talk of black power, you talk of building a movement that will smash everything Western civilisation has created’).

Images of young people singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ were replaced in the media by new ones of black men and women wearing black berets, raising their fists and carrying guns. Goals of social justice and integration were replaced by ideas of black separatism and power.

The impact of the Nation of Islam and Black Power on Black Theology

Younger blacks either started to leave the churches and some (like Muhammad Ali) went on to join the Nation of Islam, thus rejecting a Christianity that was assumed to be part of the white power structure. Black church leaders therefore faced a dilemma. Many did not want to go against Martin Luther King. Moreover whites, and some blacks, were made uneasy by the cry for black power. Some whites who felt that they had been allies in the civil rights struggle now felt snubbed. There were warnings that black power could endanger the ‘gains’ made in civil rights. Addressing some of these anxieties, in July 1966 the National Committee of Negro Churchmen issued a statement in support of the concept of black power.

Then, in 1968, Albert Cleage’s book Black Messiah urged black people to liberate themselves from white theological oppression. Though he had initially believed in integration – some of the churches he served were racially mixed – Bishop Cleage eventually came to despair of the hope that whites would ever willingly help blacks advance. He also befriended Malcolm X, the Black Muslim leader, who had Michigan roots. Arguing that scripture was written by black Jews, Cleage claimed that the gospel of a black Messiah had been perverted by St Paul in his attempt to make the Christian faith more acceptable to Europeans.

According to an obituary in the New York Times, Cleage split with both the white power structure and more moderate black leaders, and began to emphasize black separatism in economics, politics and religion. As he put it:

”The basic problem facing black people is their powerlessness,” he said. ”You can’t integrate power and powerlessness.”

Trying to counter what he saw as white domination of religion, like the Nation of Islam, Cleage promoted a gospel of black nationalism. He installed a larger-than-life painting of a black Madonna holding a black baby Jesus that was radical for its time, and preached that Jesus was a black revolutionary whose identity as such had been obscured by whites.

Subsequently, in 1969, the National Committee of Black Churchmen produced a statement on Black Theology in which it was described as follows:

Black theology is a theology of black liberation. It seeks to plumb the black condition in the light of God’s revelation in Jesus Christ, so that the black community can see that the Gospel is commensurate with the achievements of black humanity. Black theology is a theology of “blackness.” It is the affirmation of black humanity that emancipates black people from white racism, thus providing authentic freedom for both white and black people.

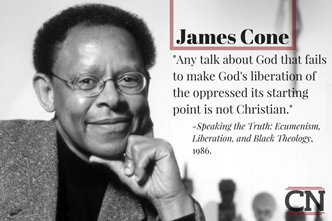

James Cone

The most significant writer within the movement is generally agreed to be James Cone (b. 1938). Cone took it upon himself to reform Christianity along lines that allowed it to be part of black emancipation rather than an implement of white oppression. He wrote:

‘For me, the burning theological question was, how can I reconcile Christianity and Black Power, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s idea of nonviolence, and Malcolm X’s “by any means necessary philosophy?”‘

James Cone, Preface to Black Theology and Black Power

Cone’s first book, Black Theology and Black Power was published in 1969 and was quickly followed by A Black Theology of Liberation in 1970. Since then he has written many books on black theology. Among these God of the Oppressed (1975) is probably one of his best known works and The Cross and the Lynching Tree (2011) is his most recent.

Cone’s theology can be summarised as follows.

First of all, he argues that all theology is contextual:

‘Theology is not universal language about God. Rather, it is human speech informed by historical and theological traditions and written for particular times and places. Theology is contextual language – that is, defined by the human situation that give birth to it.’

Cone A Black Theology of Liberation

For Cone, theology is therefore also dialectical. It comes about through a dialogue or conversation between scripture and experience. Since Cone believed that God is revealed in history as well as in the Bible, the experiences of people themselves become a relevant basis for theology. He encouraged people to ‘read the Bible through the lens of the black tradition’ and rejected the idea that it could be viewed as the objective word of God. By making use of older African religious traditions and by drawing on more recent experiences Cone thinks that it is possible to create ‘a black religious tradition unique to North America’.

Most central to Cone’s theology is the idea of the Black Messiah.

Cone argued that if you read the gospels, the overwhelming impression is that Jesus sided with the weak and the oppressed. In fact, he did not just side with them he was one of them. Born to an unmarried mother in a working class family he became a wandering homeless traveller. Criticised by the religious elite (the Pharisees) he was eventually rounded up, tried by a biased court, humiliated and abused by his captors and ultimately put to death by those in power as a victim of hate and mob violence.

For Cone, the significance of this is that if Jesus was God incarnate (Cone said ‘He is the Revelation, the special disclosure of God to man…In short, Chris is the essence of Christianity’) then this means that God chose to become oppressed. God chose to become incarnate not as a rich person with privileges but as one of the underclass.

Much like Gutierrez, Cone thought that God is not impartial when faced with injustice. God does not ignore injustice but sides with the oppressed. For Cone, in his own environment and situation, this meant that God was not colour blind. God’s willingness to side with the oppressed against the oppressor means that God sides with the blacks against the whites.

Consequently, Cone things that Jesus can be described as symbolically black. Cone uses the term ‘ontologically black’ which means that in his essence – in his inner being – Jesus is black. This does not mean that, like Cleage, Cone thought that Jesus was actually literally black (though he did point out that Jesus would not have been the blue eyed Caucasian that western Christians tend to depict him as). The point is not Jesus’ literal colour, but what he stood for. By choosing to enter into the world in such a way that he himself experienced oppression, God chose to identify with black people. This means that their struggles are his struggles and – importantly – his eventual triumph will be their triumph.

Cone draws parallels in particular between Jesus’ crucifixion and the types of violence experienced by black Americans in the twentieth century. Between the end of the nineteenth century and the mid years of the twentieth century around 3,500 black Americans had been lynched in America – mostly in southern states. Jesus’ crucifixion, whilst done at the hands of the Roman authorities, has some similarities with a lynching. Supposedly the crowds chanted ‘crucify him, crucify him’ forcing the Roman governor Pilate to accept their demands or face a riot.

If the method of his means of death reinforces his status as one of the oppressed then his resurrection is a promise of hope for a better future. For Cone, part of the significance of the resurrection is that the oppressed one triumphs.

That is why Cone has arguably added a new Christological title to the range given in the New Testament. Not only is Jesus the Son of God or the Son of David, he is also Black Messiah. Historically Jesus is ‘black’ because he sides with the oppressed (by being baptised he acknowledges his place with sinners) but as the Black Christ, the Church preaches and recognises that his resurrection marks the triumph of justice over oppression. Black theology argues the necessity of combining the Jesus of history and the Christ of Faith.

For Cone, the Jesus of history represents the basis for belief. His life becomes the standard for evaluating Christological beliefs. The Christ of white Western Theology (a meek pacifist teaching people to turn the other cheek and encouraging the oppressed to patiently accept their suffering) fails the authenticity test when compared to the Jesus of History (as found in the Gospels).

One of the most controversial elements of Cone’s teaching is that he believed that liberation should be sought through ‘any means necessary’. He justified this on the basis that black people exist within a society which is geared against them (he compared their situation to that of Jews in Nazi Germany). He said ‘white appeals to “wait and talk it over” are irrelevant when children are dying and men and women are being tortured.’ Whilst his contemporary and fellow Christian black activist Martin Luther King advocated non-violent methods, Cone associated himself with the Black Power movement which was willing to use violence to achieve its goals.

Any white/black reconciliation which was possible was to be done on black terms. White people needed to ask for forgiveness and ‘become black’ – i.e. identify with the oppressed and experience oppression before reconciliation could be achieved. Cone was exceedingly critical of white churches which had not done enough to oppose racism and segregation. He argued that their lack of action meant that they were unchristian as they had failed to stand up for what Jesus really stood for. He described white churches as the antichrist and wrote:

‘Racism is a complete denial of the Incarnation and thus of Christianity. Therefore, the white denominational churches are unchristian.’

James Cone on Martin Luther King and Malcolm X (taken from an online interview at http://www.satyamag.com/mar04/cone.html)

‘The most common misperception about Martin King is that he was nonviolent in the sense of being passive. That is incorrect and he would have rejected it absolutely. In fact, Martin King would say that if nonviolence means being passive, he would rather advocate violence. Nonviolence for him meant direct action, not passivity in the face of violence, so the world would understand how brutal the system is upon those who are poor and weak.

The most common misunderstanding of Malcolm X is that he advocated violence. Malcolm did not advocate violence but rather self-defence. He did not believe that oppressed people could gain their dignity as human beings by being passive in the face of violence. There was some tension between Malcolm and Martin largely because they tended to accept these perceptions of [each other]. But what is revealing is that Martin King came to realize that Malcolm did not really advocate violence in the same way as, [for example,] the Ku Klux Klan did. Even though he could not go along with self-defence as a form of social change, Martin King did advocate self-defence in terms of individuals who protect their home, their children, and their loved ones [from] people who would hurt them. Malcolm X came to see that Martin King’s idea of nonviolence was not passive. Actually, he wanted to join up with the civil rights movement and Martin King largely because [he saw] that nonviolent activists actually created more fear and more change than some of people within the Muslim movement. So he came to see Martin King in a much more positive light than is generally understood.’

Evaluation

1) Cone has been criticised on the grounds that his theology encourages a victim mentality among blacks. Placing oppression and victimhood at the very core of a person’s identity and allowing it to define not just the individual but an entire community actually inhibits any possibility of liberation and can exacerbate racial tension.

2) Cone arguably neglects the universal aspect of Jesus’s message, namely, agapeistic love of neighbour and even enemy, and neglects the seemingly pacifistic tone of many of Jesus’s teachings. His concept of the ‘Black Messiah’ is also arguably exclusivist as it possibly implies that white people cannot be saved by this figure.

3) Thirdly, one could question the ethics of Cone’s approach. If structural sin exists then is it justifiable to use ‘whatever means necessary’ to change it?

4) Does Cone (who eventually also incorporated Marxist ideas into his theology) place too much emphasis on people liberating themselves and not enough on God liberating people from sin. Does he focus on this life (as atheistic Marxism does) at the expense of the afterlife? (Many of the criticisms of Liberation Theology are relevant here).

Revision tip: some of the content of these notes may also prove to be useful for the topic of Equality in the Ethics syllabus, as Martin Luther King Jr is specifically mentioned in the scheme of work. It might be possible, for example, to discuss the extent to which violence is acceptable in the pursuit of equality.

Feminist Theology

Note also that this topic overlaps with another section of the 4B syllabus :

6.2 Equality and discrimination – gender

- A study of the concept of equality in Christianity, including biblical bases and emphases in Christian teaching across denominations.

- Views about progress in gender equality in Christianity and reasons for its status, focusing on the debates about the role of women in the ministry of the Church and its relationship with equality debates in society.

- The significance of these debates for individuals and the community.

Introduction

Feminism has come to be a significant feature of modern Western culture. It is a worldwide movement that strives for greater gender equality and freedoms for women, as well as a more correct understanding of the relationship between the sexes. One recent example of this is the #MeToo movement, a social media campaign that has drawn attention to the prevalence of sexual harassment and even assault in the workplace.

There have been various ‘waves’ of feminism, most notably in the l9th and early 20th Century, where the focus was on securing the right to vote for women, and again from the early 1960’s to the early 1980’s where the debate was broadened to include issues such as the objectification of women in pornography (note the possible connection with the Kantian perspective on Sexual Ethics) and reproductive rights (note the potential connection with Medical Ethics and especially abortion). A third wave of feminism, dating from the early 1990’s, has sought to embrace greater diversity and individualism within the movement, especially when it comes to defining what it might actually mean for a women to describe herself as a feminist. To an extent, this emphasis is a reflection of the current postmodern milieu.

Biblical portrayals of women

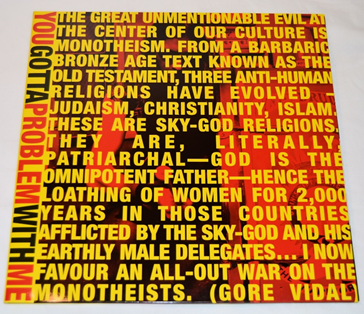

The impact of all these waves on Christian Theology has obviously been considerable, as feminist authors have been highly critical of the main world faiths, which are perceived to have treated women as second class human beings, assigned them inferior roles, and in the case of the monotheistic traditions, envisaged God in exclusively male language.

For example, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815 – 1902) helped to produce The Woman’s Bible, a highly controversial publication in which traditional interpretations of Biblical passages concerning the role and status of women were highlighted and critiqued. Meanwhile, later second wave feminist theology took inspiration from and, in turn, influenced Liberation Theology, though in the case of feminist theology the aim has been to challenge the patriarchal structures of faiths rather than to undertake a Marxist inspired critique of capitalism.

The following passage from Linda Woodhead’s book Christianity: a Brief Insight, touches on many of the concerns of feminist theologians:

‘Nowhere in the Bible is it clearly and unambiguously stated that women and men are of equal dignity and worth, that women should never be treated as men’s inferiors, that the domination of one sex by the other is a sin, or that the divine takes female form. The closest the New Testament comes to any such statements is in Galatians, where Paul writes, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

In 1 Corinthians, however, Paul explains that women should be veiled in church to signal their subordination to men because ‘the head of every man is Christ, and the head of a woman is her husband’, and that ‘women should keep silence in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, even as the law says.’

Paul’s statements exemplify a pattern in Christianity of all varieties. On the one hand, egalitarian statements are backed up in practice by equal access for both sexes to the church’s key rituals and sacraments, scriptures, and the promise of salvation. But on the other hand the egalitarian emphasis is contradicted by a symbolic framework that elevates the male over the female, and by organisational arrangements that make masculine domination a reality in church life.

Though the Christian God is sometimes said to be sexless or “above gender”, both the language and the images used to depict him are overwhelmingly masculine… He is often depicted by way of the symbols of the highest masculine authority: throne, crown, sceptre, robes, beard. “He” is Father and Son, King, Judge, Lord and Master….If the Christian God were truly sexless or above gender, it would be permissible to conceive ‘Her’ in female as well as in male terms…[But] recent attempts to introduce feminine pronouns and imagery into liturgical worship have been confined to Liberal or Mystical forms of Christianity, and have proved highly controversial.

A masculine bias is also evident in Christian understandings and representations of “man” (humanity)… Adam is created first and Eve is taken from his side. An obvious implication is that whereas man is made directly in God’s image, woman is a secondary or dependent creation – and that the image of God shines more brightly in the former than the latter. This interpretation is reinforced by the observation that Eve succumbed to sin before Adam. Many drew the natural conclusion that that if a woman is to be saved she must discipline her body and her bodily appetites more harshly than a man, since it is these appetites that brought about the Fall of the human race. The importance of virtues like humility, obedience and chastity tend to be emphasized for Christian women more than Christian men…. The idea of a natural connection between masculinity and divinity is reinforced by the institution of a male priesthood …Church Christianity located the sacred in material sacraments, but insisted that only men could consecrate, handle and distribute them. This extraordinary privilege was justified in terms of analogy between God the Father and the priestly ‘father’, a man’s greater ability to represent Jesus Christ, and apostolic succession from a male saviour through an exclusively male line.’

The response to the issues highlighted above have been varied. For example, Mary Daly has argued that Christianity, with its male symbols for God, its male saviour figure, and its long history of male leaders and thinkers, is inherently biased against women and incapable of being transformed from within. The only option is for women to abandon its oppressive environment. As Daly puts it, ‘If God is male, then the male is God’.

Another influential author, Rosemary Ruether, has criticised the persistent use of male pronouns for God within the Christian tradition, arguing that the use of female pronouns is just as valid and may, if introduced into liturgical practice, address and compensate for this excessive emphasis. In her book Sexism and God Talk, Reuther suggests that the term ‘God/ess’ is a more appropriate designation for God.

Sallie McFague has also attempted to address this issue. McFague argues that the language we use to describe God is essentially metaphorical in character, and her fundamental critique is that the language and dominant metaphors that are used in theology to talk of God in relation to the world are no longer meaningful or significant today.

We have, she argues, tended to make God in our own image in the way that God is understood. Our conceptions of deity therefore often tell us more about ourselves than they do about God. These conceptions have, in the past, consisted of patriarchal notions of God (e.g. as ‘Father’, ‘Lord’ and ‘King’- overwhelmingly masculine imagery about God) that, in turn, reflect the patriarchal societies that produced them (note possible connections with Feuerbach and Durkheim here). They have also therefore been invoked to justify unequal gender relationships in which women are seen as subject to men.

These are, McFague argues, past their sell-by date and need to be revised in the light of our present, lived experience. For McFague, a panentheistic* idea of God is best suited to our present times, as an emphasis on the world as God’s body is the best way to address our present, ecological concerns (note the connection with environmental ethics) and the need to preserve the environment.

Additionally, although God is held to be ultimately beyond gender as sexuality is a feature of the created order, feminine models of God are needed that speak more adequately to the present, lived experience of women. McFague therefore proposes the alternative metaphors of mother and lover to describe our relation with God. Additionally, the model of God as Friend may be helpful, for which there is at least some Biblical precedent, as Abraham was called the friend of God (see James 2v23).

* panentheism is essentially a combination of theism (God is the supreme being) and pantheism (God is everything). While pantheism says that God and the universe are identical, panentheism claims the God is greater than the universe but that the universe is contained within God. In McFague’s theology, thinking of the world as God’s body should inspire us to take better care of the environment.

Other feminist theologians have recommended that women may be better off reviving ancient pagan traditions ( like Julian Cope – see above) revolving around the worship of a mother goddess, or inventing new religions with a similar emphasis.

Some have also, like McFague, attempted to re-examine scripture and Christian traditions, in an attempt to demonstrate that both are open to plausible interpretations and revisions that are more appropriately reflective of gender equality. For example, they may draw attention to the fact that the male disciples of Jesus all abandoned him following his arrest, and that it was prominent women who were the witnesses to his crucifixion and the first to be present at the empty tomb. It may also be significant that although his 12 disciples were male, in the story of the Anointing at Bethany, which features in all four gospels, Jesus takes the side of the woman (usually understood to be Mary Magdalene) over and against them.

Although Woodhead (see above) claims that an unambiguous statement of ontological gender equality is never made in the Bible, Peter Vardy has pointed out that Genesis 1v26-28 has been misunderstood:

26 Then God said, “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness….27 So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.

According to Vardy, the correct translation of the word ‘adam’ in this passage should be ‘human being’ and is not specifically gendered. In fact, men and women are created together and therefore have an ontologically equal status.

The Adam and Eve narrative that then follows is widely recognised by Biblical scholars to have been written earlier than the six day creation story. Originally, it existed as a separate account that was eventually juxtaposed with the first. According to this story, Adam is created first and Eve from his rib as a ‘helpmate’. The woman therefore appears to be conferred with lower status and some theologians have said that it is her sin (allowing herself to be tempted by the serpent) that led Adam astray, thus causing women in general to be thought of as weak-minded and inferior to men.

However, the story can be interpreted in an entirely different manner. Drawing on the writing of Phyllis Trible, Vardy once again reminds us that adam is, to begin with, a word used to describe an asexual human being. It is only after the creation of Eve that a specific male and female identity is conferred on them. Male and female are therefore created simultaneously out of the non-gendered ‘earth creature/human being’. Furthermore, the term for ‘helpmate’ in the original Hebrew language is in no way meant to imply inferior status. Finally, the theological blaming of Eve can also be challenged, again with reference to the original Hebrew in which the story is written, where it is apparently clear that Adam is fully aware of what is happening when Eve is tempted, thus making him as responsible as she is when it comes to giving way to temptation.

Christian denominations and gender equality

‘No you are all women, but I am a man’ (response of a 17th Century female Quaker when criticised by men for preaching)

The Church of England has been ordaining women as priests (and more recently bishops) since 1994. However, the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches still refuse to even discuss the possibility of women’s ordination, while conservative Christian evangelicalism usually prohibits women from teaching in public (which would potentially include teaching men). Why is this?

The traditional justification for resisting the ordination of women tends to consist of the following points:

- Only a man can represent Jesus at Holy Communion.

- Jesus appointed men as his disciples and commissioned Peter as the foundation of the Church (see Matthew 16 v18-19).

- Man was created before woman and it is therefore not in the God-given order of things for a woman to speak teach in public. (1 Timothy 2:11-13 : ‘ 11 Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection.12 But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence.13 For Adam was first formed, then Eve.’)

- Because the man is publicly the ‘head of the woman’ (Ephesians 5v23) a woman’s role can only be that of homemaker.

However, arguments in favour of women’s ordination are:

- The New Testament records the roles of men and women as leaders.

- Gnostic Christianity (an early alternative strand of Christianity) included women as leaders and, according to some scholars, posed a genuine threat at the time to mainstream, patriarchal Christianity.

- As both men and women are made in God’s ‘image’ according to Genesis, they have an ontologically equal status that does not preclude the possibility of women acting as ministers.

The significance of this debate for the individual and the community

According to Linda Woodhead, in Western Christian churches women still outnumber men in most of them by a ratio of three to two. Why is this the case when Christianity has traditionally excluded women from positions of power and authority within the Church and still continues to do so in many denominations? How does Christianity continue to retain its appeal for women?

Even allowing for the fact that women’s defection from the churches is, nevertheless, one of the most important reasons why congregations are dwindling, the following suggestions have been offered:

- There is still equal access to the church’s most important rituals and sacraments.

- In Evangelical, Pentecostal and Charismatic, the experience of the Holy Spirit is available to both men and women.

- Christian churches continue to emphasise what might be seen as traditionally feminine roles and virtues, such as caring for and nurturing others.

- Women with children have much to gain from a church that is supportive of family life and exalts the domestic role of women. And after children have left home it can assign meaningful caring roles within the church for women to perform.

- Within the Catholic Church, the Virgin Mary is exalted and it does not rule out non-ordained supportive roles for women.

- The Christian church demands restraint from men too when it comes to matters like spending, sexuality and violence, which may appeal to married women who benefit from the fact that men are enjoined to respect and cherish wives, children and the home, and to honour the Christian values of love, peaceableness, fidelity, cleanliness, decorum and sobriety. (Note: men may also be attracted to a Church that sanctions gentle, loving, less macho and more spiritual expressions of masculinity.

- Women may also be attracted to the worship of a male God and saviour. If a traditionally ordered society encourages women to love, serve and devote themselves to men, then it can be quite easy to transfer the same attitudes to a God that is predominantly perceived and described in this fashion, and to ‘give their hearts to Jesus’. So in the context of more patriarchal societies, Christianity may appeal to women because of its masculine bias, rather than in spite of it.

- Within Evangelical Christianity, it is still possible for women to meet with and teach each other, in Bible study groups, prayer or healing groups. In these groups women can find support and a safe space to express concerns that they may be unable to articulate if men were present.

Conclusions

The shift towards gender equality in modern Western societies has posed a serious threat to traditional Christian imagery, teaching and organisation. In tandem with secularization, it has therefore become less relevant for many men and women, who may perceive the more conservative churches to be ‘sexist’, ‘homophobic’ or simply ‘old fashioned’. And as women come to assign greater value to their own subjective lives, they have become less willing to accept the ready-made roles into which the church would have them fit.

However, for more traditionally minded women (and men) who worry about the breakdown of family life and its consequences for children, and who may also be concerned about the loneliness, increased promiscuity and relativistic morality that all seem to be an aspect of modernity, Christianity may continue to appeal, along with its clearly demarcated gender roles.

Outside of the West, in places like Africa and Latin America, where Pentecostal, Evangelical, Charismatic and Catholic forms of Christianity are predominant, and where full gender equality may enjoy less support, Christianity continues to make headway, perhaps because of its effectiveness in maintaining a delicate balance between male and female interests. Although male privilege is usually upheld as far as the ministry of the church is concerned, an emphasis on gentler, ‘feminine’ virtues, and a teaching which entails that men exercise their power of ‘headship’ over the family in a responsible and restrained manner, together with free access to the sacraments, the Bible and the Holy Spirit, has ensured that the faith still has appeal for both sexes.