NOTE: This blog entry is aimed at students and teachers who may be interested in applying Just War Theory to the Palestine-Israel conflict (see Paper 2 topic 3.1). It also looks at whether terrorism is morally justifiable, and so is of relevance to discussions about religion and terror that may arise in the context of Paper 2 topic 4.2.

INTRODUCTION

With its rather unsettling cover depicting militants from the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades (a coalition of Palestinian armed groups), the above volume of essays consists of a wide-ranging set of philosophical responses to the question of whether acts of terror can ever be regarded as ethical. Of course, merely to consider the possibility that terrorism could be moral might be seen as abhorrent, a nettle that should never be grasped. However, given that, both now and in the past, many individuals and groups have resorted to this tactic, it does not seem unreasonable for it to be subjected to a thorough evaluation by a set of eminent philosophers in possession of the relevant expertise. So let’s see what they have to say.

In fact, most of the contributors are responding directly or indirectly to the views of Ted Honderich, who sparked a good deal of controversy (and not just in philosophical circles) when he published a book back in 2003 arguing that the Palestinians ‘have had a moral right to their terrorism as certain as was the moral right, say, of the African people of South Africa against their white captors and the apartheid state.’ Prior to this, Honderich had offered to donate the advance of £5000 he had received for writing it to Oxfam. That they turned him down is an indicator of the furore they felt this might create. In a press statement the charity explained that, ‘We believe that the lives of all human beings are of equal value. We do not endorse acts of violence.’

However, as the philosopher Julian Baggini has pointed out, more Palestinians have died over the course of this conflict than Israelis (a consequence of an Israeli policy of deliberate and disproportionate retaliation to attacks by others in order to deter them). So in the light of this policy, one of the reasons Palestinians might offer to justify their resort to terrorism is precisely because their lives are not considered to be of equal value by Israelis.

Plus, although we might be tempted to think of terrorism as ‘obviously wrong’, for Baggini that assertion still needs to be justified. And if a philosopher like Honderich thinks that terrorism might sometimes be right, then we need to do more than just respond with revulsion and dismiss his argument out of hand. So why does Honderich believe that there can be such a thing as good terrorism?

TED HONDERICH

Honderich’s argument is based on an appeal to what he calls his ‘Principle of Humanity’. According to this principle, we all desire the following: a reasonably long life of decent quality over which we are able to exercise some power and freedom, along with relationships of mutual respect (including self-respect), and a capacity to appreciate what culture has to offer in terms of knowledge, religion, and so on.

One might wish to contest this conception of the good life, but Honderich’s next move has proven to be far more of a bone of contention: those who are forced to live the worst kinds of lives by others in clear violation of the Principle of Humanity are permitted recourse to terror if this is the ‘only means’ to improve their situation. Interestingly, he maintains not only that the Palestinians have no other option, but also that Zionist terror groups like Irgun and the Stern Gang were justified in using such tactics against the British and Palestinians in order for the state of Israel to be founded.

Accordingly, some respondents to Honderich in this volume focus on whether terrorism can ever be acceptable as a last resort if all else fails, while others consider alternative possibilities available to the Palestinians that stop short of this form of violence. But before we get to them, it is worth highlighting two other aspects of Honderich’s opening chapter.

Early on in his article, Honderich affirms that, ‘After Belsen and Buchenwald, it was a human necessity that some homeland for the Jews come into being’. But he contends that this homeland should have been carved out of Germany, as ‘it was not the Palestinians who voted for Hitler in a German democracy and then ran the death camps’. This is an intriguing suggestion, but the Zionist project was already focused on Palestine, and its supporters do not appear to have wanted to start over in Germany. Furthermore, as Brian Orend points out in his study The Morality of War, Germany and Japan were able to rebuild and eventually thrive after World War Two. A more punitive approach might have therefore been counterproductive and perhaps caused the fascist and authoritarian political ideologies that had wreaked so much havoc to persist in their terrible allure. Had Honderich’s proposal been implemented, such a painful territorial loss may therefore only have created a ticking time bomb.

Secondly, this volume of essays was published in 2008, only two years after the Islamic Resistance Movement known as Hamas (a term that means ‘zeal’ in Arabic) had won Palestinian parliamentary elections and subsequently taken full control of the Gaza Strip. The Hamas Charter or Covenant is a document which sets out this organisation’s ideology. The preamble to the 1988 version states that ‘Israel will exist and will continue to exist until Islam invalidates it, just as it invalidated others before it’. A 2017 revision foregrounded the nationalist rather than religious aspect of the conflict and emphasised that Hamas’s struggle was “with the Zionist project not with the Jews because of their religion”.

However, as far as this reviewer was able to discern, Hamas has never formally offered to permanently recognise the state of Israel (though various leaders have previously expressed support for a long-term truce or hudna in exchange for a two-states solution, subject to the approval of any compromise by a majority of Palestinians in a referendum). In the light of the atrocity that took place on October 7th 2023 which triggered a war between Hamas and Israel, and the failure of Hamas to revoke their original charter, some sceptical commentators regard the revised version of it as a cosmetic exercise. For them, Hamas’s underlying aim to ‘invalidate’ Israel remains unaltered. For these reasons, it remains possible that – as someone who affirms Israel’s right to exist – Honderich may not approve of Hamas’s terrorism.

RESPONSES TO HONDERICH

Unsurprisingly, many (though not all) of the other contributors take issue with Honderich’s argument, and several articles relate Just War theory (previously described HERE) to it in interesting ways. For example, the jus in bello principle of discrimination entails that force must be directed at military targets only, on the grounds that civilians or noncombatants are innocent, while according to the jus ad bellum principle of last resort, all non-violent options must have been tried before force can be justified. But does the situation that the Palestinians find themselves in amount to a ‘supreme emergency’, an exceptional state of affairs which warrants the abrogation of the rule about discrimination? And can the notion of last resort be applied to the battlefield too, in a manner that warrants the deployment of terrorist tactics if all else fails?

The notion of a ‘supreme emergency’ is one that can be found in the writings of Michael Walzer and John Rawls. In Just War theory, a supreme emergency may arise when a state faces an existential threat from an aggressor. In other words, they are in danger of being wiped out. For example, Asma Afsaruddin has argued that the early Muslim community in Medina faced such a threat from their Meccan adversaries. For more than a decade after Muhammad had received his first revelation, he and his companions remained stoically non-violent when encountering hostility from others. But when it became clear that the Meccans harboured genocidal intentions, he received divine permission to fight in self-defence. Another purely theoretical example might arise when a country is about to lose a conventional war to a manifestly evil enemy (like the Nazis or ISIS), leaving them no option other than to use nuclear weapons to win it.

Contrastingly, Walzer suggests that the previous two scenarios are not the only ones that qualify as a supreme emergency. For him, a threat must be imminent, and it must be of a more severe nature than ordinary military defeat. Military occupation or loss of territory therefore do not meet the standard. However, the prospect of exile or the murder of a large section of the defeated population may be sufficient to trigger this exemption clause. Similarly, for Rawls, the threat of genocide warrants a response that may include the slaughter of civilians. However, any society facing such a threat must ordinarily recognise that human rights are universal in scope. For instance, Britain’s attacks on German civilians early in World War II were justified, but, had these roles been reversed, Germany would not have been justified in resorting to such attacks.

Significantly, among the other contributors to Israel, Palestine and Terror, Tomis Kapitan argues that the Palestinians do face a supreme emergency. Having established that the jus ad bellum conditions for fighting a war are met, he notes that Israel has repeatedly violated the human rights of Palestinians through acts of expulsion (in 1948 and 1967), acts of terror committed by the Israel Defence Forces (Kapitan does not mention these incidents but past atrocities either orchestrated or perpetrated by the IDF at Qibya, Sabra & Shatila, and Qana, all serve as examples), its refusal to repatriate Palestinian refugees and comply with UN Resolutions, its opposition to peace initiatives (plus, one might add, its failure to properly adhere to peace agreements that have been struck), and its assassinations of Palestinian political leaders. Effectively, the Palestinians are, for Kapitan, therefore undoubtedly confronted with an existential threat. Furthermore, he contends that as they have exhausted the possibilities when it comes to diplomacy, the use of non-violent methods to resist Israeli occupation, and conventional armed resistance to the IDF, the use of terror is warranted.

Out of the 15 articles in the book, I have focused on Kapitan’s essay because it is a model of clarity and ideal for use with bright A level students in order to show how Just War theory might be applied to this conflict. However, my view is that his overall argument fails. One reason for this is his insistence that, with the jus ad bellum principle of prospect of success in mind (according to which a war can only be just if there is a reasonable chance that it can be won), terrorism does sometimes work.

Kapitan notes that non-state terrorism committed by Jewish groups such as Irgun and Lehi/The Stern Gang was instrumental in securing a Jewish majority in what subsequently became the state of Israel. It is also, one might add, not without significance that Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir, two former leaders of these movements, went on to become Prime Ministers of Israel, as indeed did Ariel Sharon, someone who was directly implicated in acts of terror committed against Palestinian civilians at Deir Yassin and Sabra & Shatila. So, yes, perhaps the terrorists do sometimes win. And in the case of the Palestinians, Kapitan points out that recourse to extreme violence has, at least, caused external players like the USA to actively attempt to resolve the conflict, led the Israeli government to make some concessions, and, as he puts it, ‘alleviated the Palestinians sense of impotence against a more powerful adversary’.

Nevertheless, Kapitan himself admits that this approach has not secured full Palestinian self-determination, and after the events of October 7th 2023, the possibility of this goal ever being achieved seems to have receded even further into the distance, thus diminishing the prospect of success. Furthermore, given that the Israeli response of massive, disproportionate retaliation could have easily been predicted (such an assymetric response is meant to act as a deterrent and is an expression of a policy that the IDF have pursued in the past), the extraordinary suffering subsequently inflicted on the civilians of Gaza following Hamas’s atrocity seems counterproductive. Indeed, it has enabled supporters of that response to argue that the Gazans have brought all this carnage on themselves as a consequence of their support for Hamas, and that the IDF’s efforts to eradicate an organisation they regard as being hell-bent on the destruction of Israel are therefore understandable. Overall, widespread support for the Palestinian cause might thus be said to exist in spite of, not because of, the October 7th attack.

Secondly, in his discussion of the jus in bello principle of discrimination, Kapitan suggests that identifying who are noncombatants is not straightforward. This is because Israel is a democracy and in the past its adult citizens have voted into power Prime Ministers with a record of violence against the Palestinians (as noted above). So they could be regarded as legitimate targets in addition to those who are serving in the IDF at any one time. Having said that. he does insist that ‘the truly non-culpable, e.g., children, the mentally ill, and so forth, should be immune from attack.’

Such a move is not unusual. For example, the late and highly regarded Egyptian Islamic scholar Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi condemned the 9/11 attacks, but he also argued that – as Israel is a military society, one in which men and women may be called up to serve in the army at any moment – the killing of civilians is legitimated, and that if children or the elderly die in any such attacks this is involuntary killing. Additionally, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the former religious leader and founder of Hamas, has gone further and insisted that suicide bombing is both necessary and justified, regardless of who the victims are.

Overall, as Palestinian terror attacks have taken place at bus stops, in shopping malls and restaurants, places where ‘the truly non-culpable’ can all be found, it would seem that, in practice, Kapitan’s caveat is not being observed, and that there is little chance of it being adopted, thus rendering it effectively worthless. The reasons for this deserve to be looked at in detail. So let’s pause to consider them.

ISLAMIC TEACHING ABOUT WAR AND VIOLENCE

A shortcoming of this otherwise estimable volume is that it does not offer an Islamic perspective on the Palestine-Israel war. This is a significant omission, as Hamas have appealed to extenuating religious arguments to justify their use of terror. But given that mainstream Islamic teaching forbids such a form of violence, how is this possible?

First of all, it is necessary to provide a brief account of those teachings, which typically focus on al-jihad al-asghar or the ‘lesser jihad.’ This refers to the legitimate use of force against those who would ‘do evil upon the earth’ (Qur’an 2: 190 – 193).

Accordingly, if there is no alternative and everything else has already been tried, then a Muslim is permitted and indeed required to fight in self-defence. However, this notion had not yet been introduced when Muhammad and his first companions were still in Mecca and facing intense persecution. During this time, he had dirt flung at his face, rotten animal entrails hurled into his private courtyard, and a sheep’s uterus covered in excrement was thrown over him while he was praying. Also, some of the first converts to this new faith were tortured. But neither they not Muhammad retaliated. At this point these early Muslims patiently endured but also did not back down in the face of injustice and wrongdoing.

The relevant word for this is sabr. Sabr is “endurance” or more accurately “perseverance” and “persistence”. It involves remaining steadfast and continuing to do good actions even when facing opposition or encountering problems, setbacks, or unexpected and unwanted results. It entails cultivating a stoic attitude in the face of all such outcomes. In the Qur’an, sabr is emphasised in Surah 3.200, in a verse which states, ‘O those who believe, be patient and forbearing, outdo others in forbearance, be firm, and revere God so that you may succeed.’ A promise of heavenly reward for doing so is mentioned in Qur’an 39.10 and 25.75.

Only later, when Muhammad and his compatriots had moved to Medina and were facing an existential threat from their Meccan enemies was the term qital or ‘fighting’ introduced in a revelation from Allah. After that, Muhammad personally took part in 27 battles or ghazwat. However, the revelation he received made it quite clear that Muslims were only allowed to fight to protect themselves and also non-Muslims who had been attacked from the prospect of being wiped out: ‘Fight in the way of Allah those who fight you but do not transgress. Indeed, Allah does not like transgressors.’ (Qur’an 2.190).

Furthermore, if the enemy stopped fighting, Muslims were then required to do so themselves and make peace. This is reflected in the fact that when the Muslim army took over Makkah in 630 CE, Muhammad showed mercy to his enemies and did not have them executed.

A military jihad is therefore restricted in scope. It is only allowed in self-defence, to protect the oppressed or to preserve the Islamic way of life in the face of injustice. It should never be used offensively and/or in order to gain territory. There should be a good chance of success and jihad must be built on a consensus of the people (a majority must be in favour of it). Crucially, a ‘lesser jihad’ can only be declared by a legitimate ruler. Normally, this would be a Caliph, but as the Islamic Empire spread after the death of Muhammad, this power was eventually exercised by other types of leader.

Strict rules for the conduct of jihad (that are strikingly similar to Just War conditions – more on this later) were laid down in the earliest period of Islam and codified by the first Caliph Abu Bakr: minimal force was to be used and only directed against enemy fighters, and noncombatants (a category that included all women, children, the elderly, sick, and even the soldier who throws down his arms to surrender) were not be attacked or threatened. It was also forbidden to deprive an enemy of the basic means of survival. Water supplies could not be poisoned, food crops burned or destroyed, and even trees were to be spared, as they are a source of food, shelter and fuel.

These rules appear to be founded on incidents in the Prophet’s life that support the idea of protection for noncombatants. For example, a hadith (hadiths are stories about what Muhammad said and did as related by his early companions) in the collection of Musnad Ahmad states that after one battle was over, Muhammad saw the corpse of a woman who was clearly not a warrior (an important detail as women did sometimes participate in combat) among the fallen, and asked those present why she was there. They informed him that she had been killed by Khalid ibn Walid’s army. Khalid was a Muslim convert and ally of the Prophet. Muhammad then instructed one of them to run to Khalid and inform him that the killing of defenceless children, women, and servants was forbidden. Furthermore, the Prophet apparently abandoned a siege at Taif because he thought it was likely to end with the deaths of innocent women and children, who would be injured or killed by catapult shots.

So why do Hamas disregard these directives? Interestingly, their grounds for doing seem to differ from those offered by Salafi-Jihadist groups like Al-Qaeda and ISIS, who typically appeal to passages like the famous ‘sword verse’ in the Qur’an to justify their actions:

‘When the sacred months have lapsed, then slay the polytheists wherever you may find them’ (Qur’an 9:5)

Because this passage is thought to have been revealed after Qur’an 8:61 (a verse that states ‘If they should incline to peace, you should also incline to peace’), Salafi-jihadists argue that it abrogates or cancels the earlier one. For members of the terrorist organisation ISIS, ‘polytheists’ also becomes a wide ranging category which includes non-Muslims and Muslims who do not agree with their puritanical version of the faith, and this verse provides a pretext for attacks against them.

However, for more moderate Muslims, Qur’an 9:5 is specifically and only to do with Muhammad’s Meccan enemies and has no wider remit, while 8:61 refers to the ‘People of the Book’ (mainly Jews and Christians) who are not to be fought if they make peace with Muslims. So neither verse invalidates the other as they are to do with different sets of people and different circumstances.

Significantly, the September 11th 2001 attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon by Al-Qaeda were condemned by Hamas. On September 14th, the heads of Hamas, the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, the Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan, and more than 40 other Islamist movements issued this statement:

‘The undersigned, leaders of Islamic movements, are horrified by the events of Tuesday 11th September 2001 in the United States which resulted in the massive killing, destruction and attack on innocent lives. We express our deepest sympathies and sorrow. We condemn, in the strongest terms, the incidents, which are against all human and Islamic norms. This is grounded in the Noble Laws of Islam, which forbid all forms of attack on innocents.’

Hamas have also described Salafi-Jihadist movements as ‘ideologically deviant’ and sometimes taken steps to suppress the activities of this type of Salafi in Gaza. In response, being fully aware that Hamas nevertheless regard the murder of Israeli citizens as Islamically justifiable, Al-Qaeda leaders condemned what they perceived to be Hamas’s hypocrisy:

‘You will truly be surprised by those who rule that the martyrdom operations in Palestine in which civilians fall victim are among the highest forms of jihad, and then rule that martyrdom operations in America are wrong because of civilian deaths. This inconsistency is very strange! How can one permit the killing of the branch and not permit the killing of the supporting trunk?’

This is undoubtedly a valid question, even if it is being posed by the notorious architects of 9/11. But tracking down the rationale behind Hamas’s rocket attacks and suicide bombings is not at all easy. Fortunately, some clues are provided in an old BBC interview with the late founder of Hamas, Sheikh Yassin, that can be viewed HERE.

During the interview, journalist Sean Langan lists the aforementioned rules for conducting a jihad and suggests that Hamas are breaking them and undermining their cause in doing so. Revealingly, the Sheikh offers this reply:

‘One of the teachings of Islam is that we should treat our enemy as he treats us. Our God says if you are punished, you must punish the perpetrators in the same way. Our enemy has attacked and killed civilians. We have the right to defend ourselves based on what he has done to us. We’re not going against the teachings of Islam. If our enemy commits himself not to attack or massacre civilians then we wouldn’t touch any civilian.’

Here, Sheikh Yassin is probably alluding to two passages in the Qur’an:

‘If then any one transgresses the prohibition against you, transgress ye likewise against him. But fear Allah, and know that Allah is with those who restrain themselves.’ (Surah 2: 194 Tr. Yusuf Ali)

‘The recompense for an injury is an injury equal thereto (in degree): but if a person forgives and makes reconciliation, his reward is due from Allah: for (Allah) loveth not those who do wrong.’ (Surah 42: 40 Tr. Yusuf Ali)

Commenting on these two passages, Professor Asma Afsaruddin (probably the world’s leading academic authority on the concept of jihad) states that 2;194:

‘…lays down the principle of proportionality: Muslims responding to an act of aggression can do so to the extent of the original attack and only to the extent of defeating the fighting forces. Proportionality in reacting to wrongdoing is similarly stressed in Qur’an 42:40, although believers are also encouraged to forgive and reconcile with the wrongdoer instead. Given this stress on proportionality, the slaughter of whole groups of populations that include civilians is impermissible in Islamic moral and legal thought.’

Contrastingly, if Yassin did have these passages in mind, he seems to have thought that they legitimate attacks on Israeli civilians. In the same interview, he goes on to say this:

‘There’s a difference between what’s right and what’s magnanimous. If you slap me it’s my right to slap you back. If I magnanimously forgive you that’s better. But I still have the right to slap you…My conscience is very clear about what I am doing because I am not the aggressor. I’m just defending myself. And I have the right to defend myself by all means. Whoever wishes to kill me, it is my right to kill him. Whoever wants to take my home, I have the right to fight him. And whoever wants to kill my children it is my right to fight them. I’m only defending myself. The guilty conscience belongs to the violator and the terrorist who drives people from their land and takes their land by force. That’s the real terrorist.’

Again these remarks seem congruent not only with Surah 2:194 and 42:40 but also what comes immediately afterwards in the case of the latter passage. So here is verse 40 again, plus 41-43, this time translated by Afsaruddin:

‘The recompense of evil is evil similar to it: but whoever pardons and makes peace, his reward rests with God – for indeed, He does not love evil-doers. As for those who defend themselves after having been wronged – there is no recourse against them: recourse is against those who oppress people and behave unjustly on earth, offending against all right; for them awaits grievous suffering. But if one is patient in adversity and forgives, then that is the best way to resolve matters.’

So how is it that passages which appear to constrain the conduct of a jihad are being utilized by Hamas for an ‘anything goes’ form of reciprocation in self-defence?

Firstly, magnanimity is to do with rising above a situation, not letting oneself be dragged down by it. In terms of warfare, this entails treating enemies with generosity, compassion and forgiveness, instead of taking revenge on them. These qualities were all exhibited by Muhammad after his Muslim army took over Makkah in 630 CE. Instead of having them executed, Muhammad showed mercy to his former adversaries and spared them. In this sense, if the greater jihad* involves not indulging the baser emotions that comprise our lower selves, like lust for revenge, then the Prophet’s actions in this instance can be perceived as reflecting a victory in that inner struggle too. Given that Arabian society at the time was – in the absence of a police force – scarred by tit for tat blood feuds involving acts of retribution, this makes Muhammad’s magnanimity all the more resonant.

Nevertheless, at first blush, the passages we have been discussing do seem to allow some latitude for vengeance to be exacted upon an enemy, provided that one is not the aggressor, though the Quran cautions that it is better not to pursue this path. But Hamas have pursued it. For them, retaliation can even extend to responding in kind if one’s opponent is transgressing moral boundaries by slaughtering noncombatants, including children.

Have the IDF (Israel Defence Forces) deliberately murdered children? Unfortunately, the answer is undoubtedly yes. To highlight a few examples, the 1982 Sabra & Shatila Massacre of at least 800 Palestinian civilians (including women, children and babies) was perpetrated by Christian Phalangists operating in Southern Lebanon and orchestrated by the IDF. Specifically, future Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon** was found to bear ‘personal responsibility’ for the incident by a subsequent Israeli Commission of Inquiry. First of all, the IDF arranged for the Phalangists to be flown in from the south in Israeli Hercules transport aircraft. They were then given weapons, uniforms and US military rations and sent into the Palestinian camps to perpetrate this atrocity, The Israelis remained in contact while the massacre happened, watching with field glasses and dropping flares from fighter aircraft overnight so the Phalange could see what they were doing.

A very graphic account of the immediate aftermath of this act of wholesale slaughter (which is certainly not for the fainthearted or those of a sensitive disposition) authored by the veteran Middle East correspondent Robert Fisk can be found HERE.

A second well known example was the Qana Massacre. On this occasion, the IDF deliberately targeted a United Nations compound with high-explosive artillery shells. At the time, 800 Lebanese civilians, mostly Shia Muslims, were sheltering there. 106 were killed, of which 52 were children. The man who called for the barrage, Naftali Bennett, also later entered politics and became Prime Minister. Finally, from Tareq Baconi’s acclaimed study of Hamas, one learns that 634 Palestinian children were killed by the IDF between the year 2000 and Operation Cast Lead in 2008/9, while 551 died as a result of Operation Protective Edge in 2014.

Setting aside the contested issue of whether the Palestinians did or did not initiate this conflict, from a list of Palestinian suicide attacks that can be found HERE, it can also easily be established that Hamas have deliberately chosen targets for suicide bombings where children were present. Examples include the Sbarro restaurant bombing (2001), the Matza restaurant suicide bombing and the Kiryat Menachem bus bombing (2002), the Haifa Bus 37 Suicide Bombing and the Shmuel HaNavi bus bombing (2003), and the Beersheeba Bus Bombings of 2004. This is why another of the contributors to Law’s book, Timothy Shanahan, in applying Just War theory to such incidents, concludes that, ‘Suicide attacks in Israeli buses…entail the suffering, injury and death of children, the elderly, and fellow Palestinians who pose no threat to the common good of Palestinians. Such acts clearly fail the jus in bello discrimination condition.’ In a similar vein, Gerald Cohen observes in his essay that ‘Palestinians might protest that they do not aim at innocents but only at Israelis who are complicit in causing their grievance. But no defensible doctrine of complicity, however wide may be the doctrine of complicity that it proposes, will cover everybody in those Tel Aviv cafes, including the children, and the non-citizens of Israel.’

But why are all Israelis considered fair game? The posing of this question brings us to a highly contentious second aspect of the justification offered by Hamas for what they do.

Hamas insist that, as Israel is a militarized society, an occupying force, so are its citizens. Accordingly (and unlike those in the Twin Towers that were attacked by Al-Qaeda), none deserve to be treated as ‘innocent civilians’. So does this category include children because they are, perhaps, to be thought of as comprising the next generation of colonizers/occupiers, and as such will eventually have an integral part to play in the Israeli government’s future military activities?

This seems unlikely, as a Hamas leader quoted in a Human Rights Watch report (itself cited in a seminal article authored by Amy Chiang for the Chicago-Kent Law Review) made the following claims:

‘Our stand is not to target children, the elderly, or places of prayer-even though these places of prayer incite the killing of Muslims. Up until now we have not targeted schools.., nor do we target hospitals, even though they are an easy target. That is because we are working in accordance with certain values … we don’t fight Jews because they are Jewish but because they occupy our lands. So if children are killed it is something outside of our hands.‘

These remarks in all likelihood echo the views of the late Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi, a highly regarded Egyptian cleric and former head of the Sunni studies department at Qatar University. John Esposito has described him as ‘among the most influential religious authorities in the world.’ *** Qaradawi’s fatwa on the legitimacy of suicide bombings, which was briefly summarised earlier, includes this statement:

‘Israeli society is militarist in nature. Both men and women serve in the army and can be drafted at any moment. If a child or an elderly is killed

in such an operation, he is not killed on purpose, but by mistake, and as a result of military necessity. Necessity justifies the forbidden.’

This contrasts with his judgement on the September 11th attacks on the USA:

‘The Palestinian who blows himself up is a person who is defending his homeland. When he attacks an occupier enemy, he is attacking a legitimate target. This is different from someone who leaves his country and goes to strike a target with which he has no dispute.‘

In response, Chiang offers a perceptive critique of Qaradawi’s stance. First of all, she points out that some Israelis are exempted from military service. Both male and female ultra-Orthodox Jews can, for example, be excused for various reasons, as are Arab-Israeli citizens. Secondly, some Israelis are conscientious objectors who refuse conscription. Given that the phrase ‘those who fight you’ in Qur’an 2:190 is generally taken to denote only those actually fighting or preparing to fight****, the aforementioned surely cannot be held to fall into this category. Additionally, reservists arguably do not begin to prepare themselves for battle until they get called-up. Those who are too old or too young to fight, as well as anyone incapable of serving in the IDF due to physical or mental incapacity also surely fall outside the parameters of 2:190. ‘Thus’, Chiang concludes, ‘the argument that all Israeli citizens are combatants that are entitled to be attacked is weak’.

With reference to the Hamas-led attack on Israel on October 7th 2023, of the 1139 victims, 38 of the Israelis killed were children, and 71 were foreign nationals. The elderly and children were also among the estimated 250 of those taken captive, of whom about half are foreign nationals (including at least seventeen Thai citizens who were working in greenhouses in the Gaza periphery). Again, and as has already been noted with regard to the bombings listed above, Hamas would therefore appear to be directly targeting children (and noncombatants who are not Israeli citizens), and so it is disingenuous of their leadership to claim otherwise.

Qaradawi has also endeavored to show that suicide bombing is permissible. This is controversial, as two verses in the Qur’an forbid the taking of one’s own life, namely, 2;195 (‘Spend in the Way of Allah and do not cast yourselves into destruction with your own hands’) and 4:29 (‘Do not kill yourselves; indeed God is merciful towards you’). The hadith literature also prohibits suicide and warns of divine punishment in the afterlife for those who do so.

Although mindful of these passages, Qaradawi makes a distinction between those who kill themselves for personal reasons and ‘martyrdom operations’. The latter, he claims, are acts of self-sacrifice undertaken to defend the Muslim community. In the state of assymetric warfare that exists between Israel and the Palestinians, they are a valid weapon to be deployed by the weak against the strong.

In response, one earlier point needs reiterating: the assumption that suicide bombings are acts of martyrdom is based on the premise that Hamas are killing combatants rather than civilians. As previously noted, this argument does not hold water. Furthermore, although Qaradawi may have been held in high esteem, set against a backdrop of wider Muslim scholarship, his views amount to no more than a ‘minority report’. It is not possible to offer more than a representative sample of that scholarship (otherwise this blog entry would need to be twice as long), so a few examples will have to suffice.

First of all, in 2010, the Pakistani cleric Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri issued a 600-pages long excoriating condemnation of both suicide bombing and the setting aside of noncombatant immunity. A summary has been made available in English which includes the following key paragraph:

‘Terrorism, in its very essence, is an act that symbolizes infidelity and rejection of what Islam stands for. When the forbidden element of suicide is added to it, its severity and lethality becomes even graver. Scores of Quranic verses and Prophetic traditions have proved that massacre of Muslims and terrorism is unlawful in Islam; rather, they are blasphemous acts. That has always been the edict unanimously held by all the scholars that have passed in the 1400 year Islamic history, including all the eminent Imams of Tafseer [Quranic exegesis} and Hadith and authorities on logic and jurisprudence.’

Qadri goes on to address the claim (often invoked by militants) that acts performed with a good intention absolve the perpetrator from adopting the correct means to bring about a morally justifiable end. For him this is simply not possible. As he puts it, ‘an evil act remains evil in all its forms and contents’. For example, robbing a bank with the pious intention to build a mosque with the proceeds does not make this action moral. Such deeds are unethical to begin with. So in relation to Hamas, what Qadri is effectively saying is that the suicide bombing of innocents is inherently immoral, regardless of whether the Palestinian cause is just.

Focusing more specifically on whether suicide attacks are acts of martyrdom, in 2006 the Saudi scholar Muhammad ibn Salih al-Uthayman invoked Qur’an 4:29 to declare that they do not represent an exception to the prohibition on suicide. Rather, those who undertake such missions are motivated only by a desire for revenge, which renders them unlawful. Similarly, the well-known scholar of hadith Muhammad al-Albani has been quoted as saying that so-called ‘martyrdom operations’ are uniformly unlawful and ‘a form of suicide which causes a person to remain in Hellfire eternally’. Additionally, Sheikh Muhammad Sa’id Tantawi, the former head of Egypt’s Al-Azhar mosque and university, declared that Shariah ‘rejects all attempts on human life, and in the name of the Shari’a, we condemn all attacks on civilians, whatever their community or state responsible for such an attack’.

In conclusion, the pattern that emerges from a close and holistic reading of the relevant Quranic passages and hadiths reveals that the prohibition on suicide is absolute, that a lesser jihad must only be conducted defensively, that only those actually engaged in battle or who, at best, are preparing to fight are to be regarded as combatants, and that when it comes to reciprocity, self-restraint is recommended. Indeed, as Amy Chiang points out, ‘after every Qur’anic verse permitting reciprocity is a verse ordering restraint and forgiveness’. This, in turn, accounts for why Asma Afsaruddin regards Qur’an 2:194 as echoing the jus in bello principle of proportionality rather than as a mandate for attacks against civilians. Furthermore, the conferring of combatant status on an entire nation is not a notion that is consistent with any sacred textual source in Islam.

Afsaruddin also raises the intriguing possibility that the development of jus in bello conditions governing the conduct of war by the 17th Century Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius may bear traces of Islamic influence. Noting the striking congruences that exist between the two sets of principles, she thinks it possible that three Spanish jurists who were acknowledged influences on him were themselves operating in an intellectual environment that followed from an extended period of prior Muslim rule, making it not unreasonable to imagine that they may have been in some way familiar with long established codes governing the protection of civilians that were already embedded in that culture.

Staying with the discussion of Just War theory a little longer, other contributors to Law’s volume offer further valuable insights about it. For example, Patrick Riordan cautions against any ‘cynical’, ‘self congratulatory’ use of Just War doctrine. By this he means that it should not be invoked by one of the sides in a given conflict to create the false impression that they are behaving more morally while the other side are not. Honderich too, in a postscript at the end of the book, notes that the theory is open to manipulation. This also perhaps explains why Chomsky’s article is notably guided by what he calls the ‘principle of universality’. What this principle states is that, at the very least, we should apply to ourselves the same standards that we apply to others. This is a principle that Chomsky claims has always been central to any system of ethics (and it could be a maxim based on the first formulation of Kant’s categorical imperative).

Often we use ethical language to criticise others but are less inclined to hold ourselves to the same standards. Nevertheless, if we claim to be on the side of right against wrong and if we wish to be consistent, Chomsky maintains that his principle is one that we must stick to. In particular, he argues that we should be very careful about what our governments say are the ‘facts’ about any given situation and see if they are upholding this ethical standard. When we do this, Chomsky contends that we often find that our governments do not uphold the same ethical standards that they often accuse other countries of violating. In other words, we should not assume that, say, our own government is naturally more ethical than other governments.

One way in which governments and other parties to a conflict can be seen to violate Chomsky’s principle is when they accuse their enemies of terrorism but refuse to accept that they may also be deserving of this label. The veteran Middle East correspondent Robert Fisk highlighted this tendency in his book Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War:

Already, we have seen one Hamas leader dishonestly claim that they are not deliberately targeting children and the elderly. How about the Israelis? Gerald Cohen thinks that they have what is known as a tu quoque or ‘you also’ case to answer. This much becomes apparent when the principle of double-effect is invoked. According to this principle, which can accompany the jus in bello rule about using force only against the opposing side’s military, violence perpetrated directly against civilians is prohibited. However, if that violence is a foreseen but unintended consequence of military action taken to achieve an otherwise morally desirable outcome, it is deemed justifiable. In other words, if an action has two effects, one that is ethically good and the other morally bad, the action is adjudged moral if the latter is an unintended side-effect, even if the person or persons committing it knew that this might happen.

Noting that ‘some…Israelis invoke the principle of double-effect’ to claim the moral high ground, Cohen is unimpressed. As he puts it, ‘I believe, for example, that, holding everything else equal, such as, for instance, the amount of justice that there is in the cause, killing 200 innocents through foreseeable side-effects is actually worse than killing one innocent who is your target.’ It would therefore seem that this principle fails in the light of such comparisons, in addition to falling foul of Riordan’s earlier point about any supercilious use of Just War theory when it comes to the IDF.

Another Just War precept that merits further consideration is the jus ad bellum rule concerning probability of success, one that can also be found among the ordinances governing the conduct of a lesser jihad. When applied to the Palestine-Israel conflict, the first point that needs to be made is that, as was previously noted above, sometimes terrorists do win. According to Andrew Silke, between 6-10 per cent of of terrorist conflicts end with the terrorist group triumphant. Of course, if one perceives the Israelis to be practitioners of state terrorism, then this statistic needs to be heeded by them too. But purely with Hamas in mind, it indicates that they have a 90-94 per cent chance of losing.

Furthermore, the IDF enjoy military superiority over their adversaries and it is well-known to historians of this war that, as a matter of policy, they subscribe to the Dahiya doctrine. This is a military strategy that entails responding to violent provocations with excessive, extravagant displays of force, which include the destruction of the enemy’s civilian infrastructure. The disproportionate number of civilian deaths inflicted by the IDF on the Palestinians during the history of this conflict is therefore a consequence of the adoption of this strategy.

These considerations notwithstanding, in a June 2024 article for Foreign Affairs magazine, Political Science Professor Robert Pape has claimed that Israel’s latest iteration and application of the Dahiya doctrine in the wake of the October 2023 atrocity has been counterproductive, to the extent that it can even be said that Hamas are winning. For Pape, this is because their insurgent tactics are proving to be surprisingly effective. Hamas, in other words, are not being eradicated. Furthermore, the IDF’s asymmetric response is merely inspiring the Palestinian heirs to the conflict to rally to the Hamas cause. On closer inspection, however, the future situation Pape appears to be envisaging is one in which the conflict is only perpetuated rather than won, as a new generation of Hamas fighters displaces the present one.

So if there is no chance of achieving success through the use of violence, let alone terrorism, are there any other options? In his contribution to Israel, Palestine and Terror, the editor Stephen Law tentatively suggests that there might be in his essay ‘Terror in Palestine: A Non-Violent Alternative?’

Noting that non-violent methods have been historically successful on many past occasions (examples include the Civil Rights movement in the USA in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Indian independence movement, the nonviolent revolutions in 13 countries in the former Eastern Bloc in 1989, the toppling of the Marcos dictatorship in the Philippines, and the ending of apartheid in South Africa), Law is quickly able to establish the efficacy of such an approach.

However, as he readily admits, the adoption of non-violent tactics by the Palestinians has met with a frequently brutal response on the part of the Israelis. Among several examples described in Law’s article, the tax revolt initiated by the residents of the mainly Christian town of Beit Sahour is probably the most well-known. During the 1987- 1993 first intifada or ‘uprising’ against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, this middle-class community of around 12,000 citizens responded to a call from a coalition of local Palestinian leaders to stop paying taxes to Israel. ‘No taxation without representation’ said a statement from these organisers. ‘The military authorities do not represent us, and we did not invite them to come to our land. Must we pay for the bullets that kill our children or for the expenses of the occupying army?’ Accordingly, the people of the town began a strike.

However, the protest provoked the IDF into placing Beit Sahour under curfew for 42 days. Food shipments were blocked, telephone lines to the town were cut, reporters and the consuls-general of Belgium, Britain, France, Greece, Italy, Spain and Sweden were denied access to it, ten residents were imprisoned, and assets worth millions of dollars in money and property belonging to 350 families were seized. Nevertheless, the citizens obdurately persisted in their protest. Ultimately, Israeli troops ended their near-siege after six weeks.

A second example cited by Law is the 1988 Sol Phryne incident. The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) had purchased a ship bearing this name with the intention of returning 135 Palestinian deportees to the port of Haifa in Israel in a symbolic recreation of the voyage of the SS Exodus in 1947, a ship bearing passengers who were Holocaust survivors. These refugees were denied entry by the British authorities, who at the time were responsible for the administration of what was then known as Mandatory Palestine. The Sol Phryne, which had been renamed renamed Al Awda or ‘the Return’, fared no better. Three high-ranking PLO officials who had orchestrated this action were assassinated in Limassol, Cyprus when a remote-controlled bomb that had been affixed to their car was detonated. Eighteen hours later, on the night of 15 February, the hull of the Al-Awda was breached when a limpet mine exploded. This ruptured the fuel tank and caused the ship to list. There were no reported casualties but the damage ended the attempt. Although Israel denied responsibility for these acts, a minister cautioned that any repeat attempt on the part of the PLO would meet with the same result.

Are non-violent methods worth persisting with if they elicit this type of harsh response? Law’s opinion is that they are, provided that such acts are pursued uniformly and are not accompanied by other, violent deeds, which inevitably attract more media attention and allow Israel to get away with portraying itself as a victim rather than being perceived as an oppressor. Additionally, Hamas would, he argues, need to state what it wants unambiguously. Even in its revised form, the Hamas Charter does not appear to meet this requirement. Thirdly, Law thinks that passive resistance on the part of the Palestinians would need to be better organised and co-ordinated, and entail an absolute commitment to non-violence.

Is this even possible, given the tensions that currently exist between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, and the presence of even more militant factions in Gaza, such as Islamic Jihad and the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, that would need to be compelled to fall in with this commitment.

In connection with this question, one point that needs to be made is that both Hamas and the Palestinian Authority have enjoyed some success in the past when it comes to reining in such groups in order to observe truces with the Israelis. But on the other hand, Hamas could point to the fact that the renunciation of violence by the PLO did not result in a satisfactory land for peace deal with the Israelis. Nevertheless, some kind of two-state solution or a binational state with equal rights for inhabitants do seem to be the only viable options for a resolution of this seemingly intractable conflict.

Having said this, there is yet another issue that would need to be addressed if non-violence were to be unilaterally adopted by Hamas as a stratagem, namely, whether such an approach can be justified Islamically. For Law, writing at a time prior to Hamas’s political ascendancy, this was not a matter for consideration. But itnow seems perfectly reasonable to investigate whether there is any precedent for such a bold move.

Fortunately, a whole chapter of Afsaruddin’s study of jihad is devoted to this topic. At the outset of it, she draws attention to the fact that the Qur’an consistently favours peace over conflict and encourages such an approach even in the face of hostility. In particular, she cites surah 25:63 and 8:61 to support of this observation. In Arberry’s acclaimed rendering, these passages read as follows:

‘The servants of the All-Merciful are those who walk in the earth modestly and who, when the ignorant address them, say, “Peace”‘.

‘And if they incline to peace, do thou incline to it; and put thy trust in God; He is the All-hearing, the All-knowing.’

Furthermore, she points out that the Arabic term salam, which means ‘peace’, is closely related to the word ‘Islam’, and that Muslims typically greet each other with the salutation “Peace be upon you” (as-salam alaykum), adding that peaceful relations are also encouraged in the hadith literature and envisaged as an eventual outcome of the implementation of Shariah law. Having said this, Afsaruddin nevertheless reminds her readers that Islam is not a faith that enjoins absolute, unconditional pacifism. Rather, she regards the term ‘pacificism‘ as more accurately representative of Islamic teaching about peacemaking. Indeed, as the Wikipedia entry for this relatively new concept affirms, pacificism recognises that although nonviolence is preferable, force may sometimes be exceptionally required to ‘encourage what is good, and forbid what is evil’ (Qur’an 3:104) an ethical injunction that applies to every Muslim.

It would therefore seem that if resort to a variety of peaceful means is still a viable option, as Law maintains, then such an approach is to be preferred. And as Afsaruddin’s excellent study also reveals, there is no shortage of modern Muslim scholars who regard nonviolence as the best way to promote good and combat injustice. In fact, there are several who have come very close to embracing pacifism, like the Syrian thinker and peace activist Jawdat Said (the Italian translation of his book Non-Violence – The Basis of Settling Disputes in Islam is depicted above),who has been called the ‘Circassian Gandhi’.

The basis for Said’s theology resides with his exegesis of Qur’an 5:27-31:

And recite thou to them the story of the two sons of Adam truthfully, when they offered a sacrifice, and it was accepted of one of them, and not accepted of the other. ‘I will surely slay thee,’ said one. ‘God accepts only of the godfearing,’ said the other. ‘Yet if thou stretchest out thy hand against me, to slay me, I will not stretch out my hand against thee, to slay thee; I fear God, the Lord of all Being. I desire that thou shouldest be laden with my sin and thy sin, and so become an inhabitant of the Fire; that is the recompense of the evildoers. Then his soul prompted him to slay his brother, and he slew him, and became one of the losers. Then God sent forth a raven, scratching into the earth, to show him how he might conceal the vile body of his brother. He said, ‘Woe is me! Am I unable to be as this raven, and so conceal my brother’s vile body?’ And he became one of the remorseful.

For Said, a number of Kant-like imperatives can be derived from this passage. Firstly, Muslims are prohibited from calling for the killing or assassination of others or the incitement of any such act (Ayatollah Khomeini’s controversial fatwa or legal ruling against the novelist Salman Rushdie immediately springs to mind). Secondly, they should not use force to compel others to accept their views, nor should they submit to others out of fear that force will be used against them if they fail to accede. Said here is referring to what has been called a ‘jihad of the tongue’, or in more conventional parlance, ‘speaking truth to power’. In one hadith, Muhammad himself affirmed that such a line should be taken even with a tyrannical ruler. In doing so, Muslims would thereby be observing a third imperative, namely, an obligation to not deviate from the path of truth as delineated by all the prophets of Islam. Such an adherence to truth was further demonstrated by Muhammad in another hadith, one in which a Companion of his asked what he should do if an intruder entered his home with murderous intent. The Prophet’s answer was that he should emulate Adam’s first son. Muhammad then cited the above passage from the Qur’an. For Said, this means that resorting to violence, even in self-defence, is impermissible.

So what does Said make of the passages in the Qur’an that sanction the fighting of a lesser jihad? In the absence of a properly formed Islamic community, he maintains that a military jihad cannot be authorised. As such a community or elected government does not presently exist (one devoted to the establishment of justice and the ending of persecution), Muslims are required instead to practise peaceful, nonviolent activism in accordance with the teaching of sabr, best exemplified by Moses, whose sangfroid in his interactions with Pharaoh serves as an example for others to follow.

One implication of this reading of the story of Moses is that Muslims should not seek the violent overthrow of despotic governments, as those who do would be emulating Pharaoh. Said was a Syrian-Circassian Islamic scholar who lived through the autocratic presidencies of Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashir, so this is something he had experience of, having already been repeatedly arrested for expressing his views . Faced with violent Islamist uprisings against their authoritarian rule, both Assads responded with brutal measures. See, for instance, the interview below with the aforementioned Middle East correspondent Robert Fisk, who was an eyewitness to the Hama massacre. He describes the ‘scorched earth’ policy of indiscriminate bombing pursued by the elder Assad that resulted in the ‘genocidal massacre’ of at least 20,000 inhabitants of the city, many of whom were innocent civilians.

Described by Patrick Cockburn as ‘the best reporter I have ever known’, and by the philosopher Noam Chomsky as ‘truly great’, Fisk was also one of only a few Western journalists to interview Osama bin Laden. His reportage, which has already been referred several times here, repeatedly exposes the utter hypocrisy of the politics of the region, as well as that of our own and the US governments’ reactions to events there. Although not without its flaws, Fisk’s publications are recommended reading for anyone whose interest in Middle Eastern affairs has been piqued by this blog entry.

Just in this brief 2012 clip, Fisk notes that Rifaat al-Assad, the younger brother of Hafez and the major architect of the Hama massacre, an obvious war criminal, was being permitted by the then government of David Cameron to live a life of luxury in Mayfair, London.

Fisk was also a pacifist. He claimed that anyone who saw the carnage and bloodshed that he had observed first hand on so many occasions would be compelled to adopt that position. Contrastingly, for Said, qital or fighting is not categorically forbidden, but should only be initiated by mature and rational authorities who know what they are doing. Recalling Qur’an 2:256 (‘Let there be no compulsion in religion’), Said was especially scathing about ‘preachers of terrorism’ who, through their cynical distortion of Islamic teaching about jihad, have ’caused more harm to Muslims than any other malpractice.’ Their theology ‘must be quelled with any possible means’.

Another prominent advocate of nonviolence (one of several mentioned by Afsaruddin) whose thinking deserves to be highlighted here is the recently deceased Indian scholar and former president of the Islamic centre in New Delhi, Wahiduddin Khan. Khan envisaged jihad as essentially a peaceful, internal struggle against one’s ego, and regarded sabr as an outward expression of this struggle. Passages in the Qur’an that he cited as proof-texts for his views include 25:52 (‘So, (O Prophet,) do not obey the unbelievers, and fight against them with it (the Qur’ān), in utmost endeavor’) and 22:78 (‘Strive for Allah with the striving due to Him’). In the former passage, ‘fighting’ here refers to an irenic form of disputation, a verbal rather than physical battle to uphold and propagate truth in the face of falsehood, while the mention of ‘strive’ (‘jahidu’) in the latter points to a predominantly nonviolent struggle that should only be departed from in extremis.

As has already been noted, the nascent Muslim community in Medina would have been completely snuffed out by the Meccans, so armed resistance was necessitated by these exceptional circumstances. Khan therefore readily acknowledges that divine sanction for this act of self-defence is enshrined in Qur’an 22:39 (‘Permission to take up arms is hereby given to those who are attacked’), and 9:13 (They were the first to attack you’) . However, he also draws attention to the fact that prior to this, the Prophet had only verbally challenged Meccan polytheism, meeting abuse and criticism with nonbelligerent passive resistance. The eventual hijrah or migration of Muhammad and early converts to his faith from Mecca to Yathrib/Medina in 622CE can also be seen as a means of avoiding physical confrontation. Furthermore, during the eventual conflict with his Meccan enemies, the Battle of the Trench in 627 resulted in minimal casualties (Afsaruddin claims that ‘no fighting actually occurred’, but in his biographical study Mohammed, Maxime Rodinson states that, ‘In all, there were three dead among the attackers, and five among the defenders of the oasis’). For Khan, the adoption of this tactic shows that those defenders wished to avoid killing whenever possible. He also contends that the 628 Treaty of al-Hudaybiyya was signed by the Prophet in order to avoid unnecessary bloodshed, and the peaceful conquest of Mecca in 630, following which Muhammad declared an amnesty for past offences, again demonstrates that the preferred ‘weapon of the Prophet’ was nonviolence.

In his book The True Jihad: The Concept of Peace, Tolerance and Non-Violence, Khan is emphatic that Quranic instructions to fight were ‘specific to certain circumstances’ and ‘not meant to be valid for all time to come’. Authored in the aftermath of 9/11, Khan’s study is highly critical of perpetrators of acts of terror, including suicide bombing. Like Jawdat Said, he insists that armed conflicts can only be initiated by a ruling government and that civilians should never be targeted. Suicide bombings are further condemned as inauthentic acts of martyrdom, as they entail the deliberate courting of a martyr’s death, which is a complete departure from Islamic teaching. Overall, Khan affirms that the best way to realize the will of God is to always be guided by Qur’an 10:25 (‘And God summons to the Abode of Peace’).

The theology of Jawdat Said and Wahiduddin Khan has been described in detail because are both representative of a wider trend in contemporary Islam, namely, that of peaceful scholar activism. Indeed, they are by no means isolated examples, nor are they on the fringes of modern Islamic scholarship. It therefore turns out that there is a basis for the approach to the Palestine-Israel conflict advocated by Law. However, the importance of figures such as Said and Khan should not be exaggerated. Indeed, it would still probably take a considerable shift in the Overton window of Islamic politics for the ideas they promote to become mainstream. But, taking into account the condemnations of suicide bombing and attacks on civilians by more orthodox scholars whose opinions were described earlier, there is hope that such a shift might eventually occur. So perhaps Law is unduly pessimistic at the end of his article. When contemplating the possibility that some kind of non-violent mass movement might arise in the future, he suggests that, if it is unrealistic to ever expect one to come about, then Palestinians who draw the same conclusion might then be individually justified in resorting to violence or terror (though Law himself remains dubious about whether individual actions of this kind are warrantable).

We are now nearly at the end of this blog entry. So at this stage it is appropriate to reconsider our original question: can there ever be such a thing as ‘good terrorism’, whether engaged in as an individual or collective act? As many of the contributors to this outstanding collection of essays (not all of whom have been acknowledged in this review) have shown in response to Ted Honderich’s insistence that there can, there will always be an epistemological problem lurking in the background whenever such a drastic step is contemplated. The problem is this: how can you know that all possible alternatives have been tried and that terrorism is the ‘only means’ available to you? Or, following Law, is it possible that one of those alternatives might work second time around, when pursued in a slightly different fashion?

Honderich’s appeal to past examples where the consequences of terrorist actions achieved significant moral outcomes is, nevertheless, surely worthy of attention. Although not mentioned by Honderich, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, an act of insurrection that arguably helped to hasten the abolition of slavery, has been cited as a classic instance where there was such a good outcome. On the other hand, the fact that such judgements can only be conferred retrospectively somewhat thwarts the overall case Honderich is trying to make. All that we can know, it would seem, is that some previous incidents deemed to be acts of terror had consequences that – from a consequentialist perspective – render them justifiable. What we cannot know is whether the same ethical result might have come about without recourse to violence. Additionally, any choices made now, on the available information to hand, have to be made against a backdrop of uncertainty that perhaps exposes the weakness of consequentialist approaches to ethics, if a high degree of certainty or confidence that we are doing the right thing is something that we can reasonably demand of any viable moral theory.

Contrastingly, when it comes to Islamic teaching about war, peace and terror, matters are more clear-cut. The overwhelming scholarly consensus is that acts of terror are impermissible, even when many such heinous acts have been gratuitously perpetrated by the IDF. So what is now perhaps needed is for this clarity to be conveyed to Hamas through the exertion of theological outside pressure by those who are in a position to influence them. If someone is better equipped to stake a claim to the moral high ground in this conflict, then curiously, if Hamas can somehow be compelled to renounce their charter and adhere to traditional Islamic teaching on warfare, they might be better placed than their adversaries to occupy it.

*Although Islam teaches that every human being is born a Muslim (in the sense that they have a natural tendency to worship God and to bring themselves into conformity with his will), it is easy to drift off into disobedience. For this reason, every individual Muslim is required to make jihad. They have a duty to struggle against their wayward self and to strive to become a better person. This form of jihad is known as the ‘greater jihad’. In other words, the greater jihad is an internal, personal spiritual struggle which contrasts with the lesser jihad, which is an external, collective physical struggle. This contrast is best illustrated by a famous hadith. After returning from battle Muhammad told his followers, ‘We return from the lesser jihad to the greater jihad’. The greater jihad is regarded as the more difficult and important endeavour. This is because unless evil in oneself is conquered, then a Muslim is in no position to right the wrongs of the world.

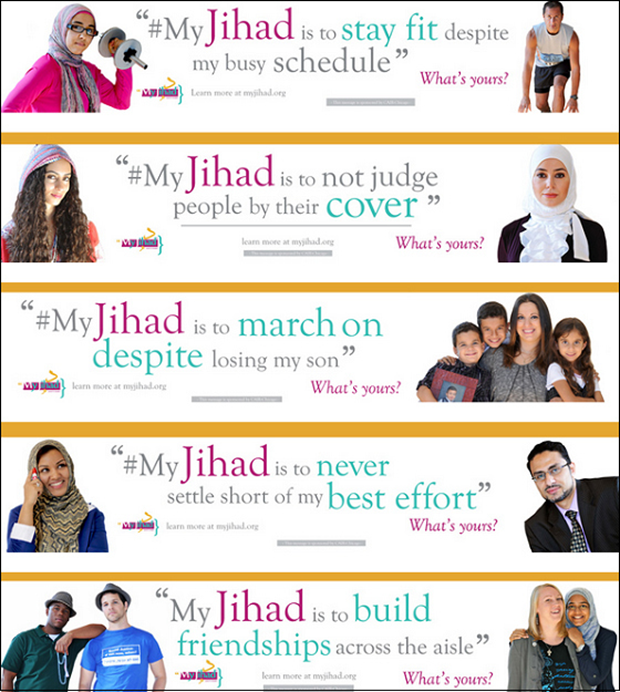

Examples of making the greater jihad might involve things like trying not to lose your temper, being more forgiving, letting go of pride and hatred, and so on. Here are some more:

**See also the more direct part he played as a Military Commander in the much earlier Qibya massacre.

*** Esposito, John, What Everyone Needs To Know About Islam, second edition, Oxford University Press, pg. 144

**** In his commentary on the Qur’an, the late 12th Century exegete Fakhr al-Din al-Razi insists that Qur’an 2:190 is directed only at actual not potential combatants. In other words, fighting is only permitted against those already on the battleground and not those who are capable of fighting or preparing to fight but have yet to resort to actual violence.