THIS REVIEW MAY BE OF INTEREST TO STUDENTS AND TEACHERS WHO ARE TASKED WITH LOOKING AT LIFE AND DEATH/THE SOUL AND RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE.

Studying religion can sometimes be a rum business. Take the late Martin Riesebrodt, for example. He was a sociologist who defined the subject (or rather religion itself) as a ‘legitimate form of science fiction.’ And if ‘world expert on zapping and mutation’ Jeffrey Kripal*, who holds the J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University, and is a co-author of the above title is to be believed, this is a definition that deserves to be taken very seriously:

‘Some of the best and most popular science fiction writers of all time had jaw-dropping paranormal experiences, and that’s why they wrote the stories they wrote. It’s the paranormal that produces the science fiction, and then the science fiction loops back and influences the paranormal…The whole history of religions is essentially about weird beings coming from the sky and doing strange things to human beings…historically, those events have been framed as angels, or demons, or gods, or goddesses, or what have you. But in the modern secular world we live in they get framed as science fiction.’ (page 133 quoting Kripal in Brad Abraham’s wonderfully bonkers documentary Love and Saucers).

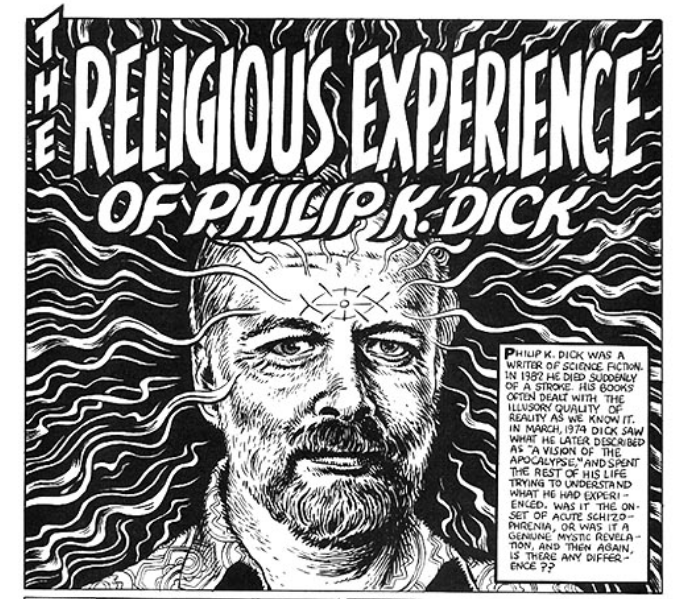

What Kripal refers to as looping back will be explained later. For the moment, let us simply acknowledge that he may well be on to something. For example, Philip K. Dick, whose novels and short stories were made into the movies Blade Runner, Minority Report and Total Recall is one such author who had a profoundly transformative paranormal experience. He then spent the rest of his life trying to make sense of it through his later Valis trilogy and a vast journal, which even in its substantially edited published format extends to more than 800 pages.

The well-known countercultural cartoonist Robert Crumb has helpfully produced a comic book version of Dick’s extraordinary vision that is well worth reading and can be found HERE.

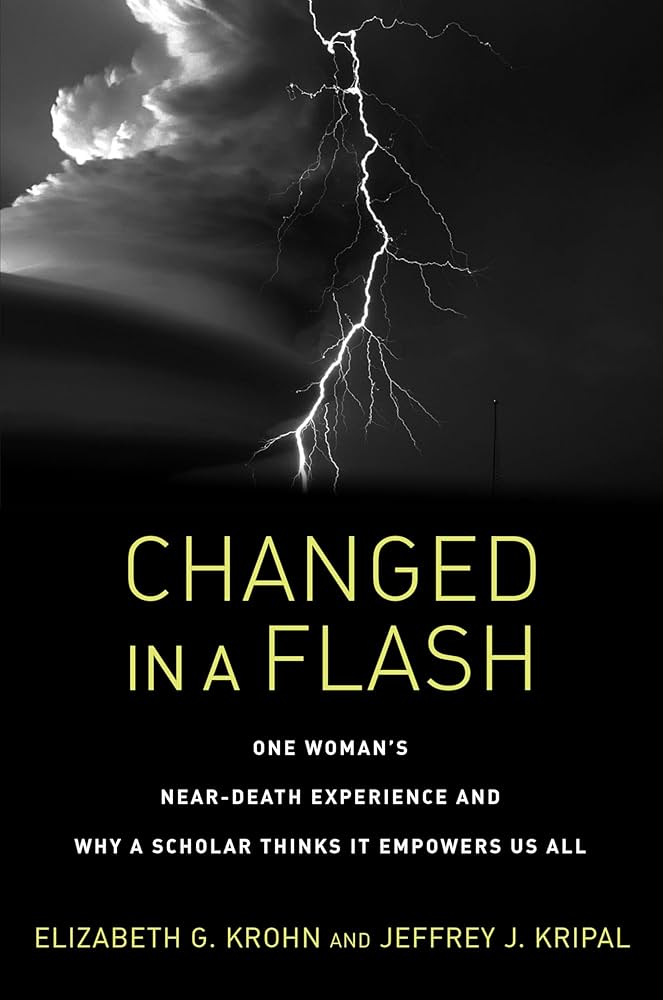

As Riesebrodt and Kripal both assert, religions are indeed hewn from the raw material of religious experience. But if this is the case, then we are getting ahead of ourselves. This review should have started with Elizabeth Krohn getting struck by lightning. So let’s take a look at her account of the incident and its aftermath, which is recapitulated in the first half of the book.

Apparently, between 30 and 60 people are hit in any given year (one person for every 1,118,016 people according to the UK Office for National Statistics), with hill walkers, climbers, golfers and agricultural workers most at risk. In Krohn’s case she was in the parking lot of her local synagogue and making a dash for the entrance in the middle of a thunderstorm whilst unwisely clutching an umbrella. Fortunately, she survived, though the strike was the catalyst for an extended NDE or Near Death Experience, one that was accompanied by an unusual episode of time dilation. Although Krohn calculates that she left her body for only a couple of minutes, she claims to have spent two weeks in an Edenic-like ‘Garden’ (typed with a capital ‘G’ throughout her account) conversing with a spiritual companion that she took to be God speaking with the voice of her late grandfather.

The event itself took place in September 1988, and during it knowledge of future events was imparted to Krohn. She was told that George W. Bush would ascend to the US Presidency, that she would subsequently give birth to a daughter (though her marriage would end in divorce), and that – somewhat incongruously – the Cincinnati Bengals would play in the 1989 Super Bowl. All these predictions turned out to be true. More generally, she was also informed that reincarnation was a fact, and that if she decided to stay in eternity, her ‘future daughter would simply select other parents’.

The lightning strike also caused Krohn to acquire new attributes. She became more comfortable with ambiguity and less predisposed to binary, either/or, black and white thinking or judging. As a practising Jew, she abandoned the exclusivist view of faith which regards only one denomination or religion alone as being the true path to God. Additionally, she became synaesthetic. Synaesthesia is a rare and benign neurological condition that involves a blending of the senses. It affects people in different ways. Some might ‘see’ sounds, ‘taste’ a voice or shape, or visualize a number in a 3-D format. It is thought to be inheritable and not a quality that arises suddenly and spontaneously.

More notably for our purposes, Krohn also became endowed with paranormal abilities. The most significant was a precognitive faculty that typically (though not always) expressed itself when she was dreaming. This enabled her to foresee the death of a stranger, as well as dramatic events such as the 2009 Hudson River plane crash, and the Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011. She was also able to see auras, the energy fields that allegedly surround human beings. Auras are colourful, and those that are dark grey or black tend to be associated with tiredness, low mood, or illness. Krohn herself reports that when she saw a relative with a black aura, shortly afterwards they suffered a heart attack and died.

For a time, she deployed these capabilities to perform psychic readings, during which she would interact with the disembodied spirit guides of her clients. Something else that Krohn found herself able to perceive was a spirit that lives in her house, a presence that was also sensed by one of her sons, a family friend, and her pet dog. Less predictably, she also found that her own presence would sometimes have an effect on electrical objects that were in proximity to her. Watches, wrist-worn activity monitors and pain relieving devices would all inexplicably cease to operate, and light bulbs would blow out when she walked past or under them.

But perhaps the most astonishing incident of all that Krohn recounts in the book is the telephone call she received from her dead grandfather, requesting her to pass on some private information to her still living mother. Following their conversation, her bedroom then became filled with what she describes as an odorless mist, smoke or vapour. All of this was witnessed by her husband at the time.

So what does Krohn’s co-author, Jeffrey Kripal, make of her remarkable story? And what are we to make of Kripal’s evaluation? There may be a lot to take in here, but he is adamant that this is what we should do; we should (in accordance with Richard Swinburne’s well-known principles that commonly feature on A level syllabuses in Religious Studies**) take Elizabeth Krohn’s testimony at face value, and not treat it with incredulity.

Of course, what Kripal then has to acknowledge is the challenge that this provisional acceptance immediately then poses for a materialistic view of reality, one which regards the mind or consciousness as a product of the brain, and matter as, well, just purely material. According to such a world view, what follows from this is that there can be no leave-taking of the body by such a thing as the soul, no precognition (because we always remain tethered to the present moment in terms of perception), and no clairvoyance (because we are marooned in the physical space we occupy).

For Kripal, anomalous experiences further suggest that ‘the assumption that the only way to know the truth of the world is through the present scientific method’ needs to be questioned, as this approach excludes the subjectivity that paranormal events are predicated on, given that they appear to be exhibitions of ‘the mind’s power over or within matter or “objects”.’ So what is needed is a model that can handle them. What would such a paradigm look like?

In the case of NDE’s, Kripal is at pains to try to show how they can be simultaneously similar (experiencers typically report leaving their body, finding themselves in a landscape that may seem like a spiritual realm where they encounter deceased loved ones and/or sacred figures, feel utterly at peace and bask in a sensation of unconditional love, and so on) and yet so different for each individual (in terms of their descriptions of the realm, who they encounter, the knowledge that is imparted to them etc.). Having noted that experiencers frequently appeal to the imagery of film and television in their attempts to relate what happened to them***, to account for this Kripal deploys the analogy of a cinema projector and screen.

To understand his analogy, the first thing we need to take note of is that everything we experience through our senses comes to us secondhand. Raw, unfiltered reality inevitably gets neurologically processed by our brains first. So what we are presented with is not reality as it is in itself. The events unfolding on screen with which a cinemagoer readily identifies correspond to this secondhand version of reality that our brain creates for us. Given that we are imaginative creatures, what we experience in an NDE will therefore also contain features that are unique for each individual because of this.

As Kripal goes on to explain, the events on screen that we are caught up in may not be real. But the light is, as is the source of that light (the projector) and, perhaps, the elusive projectionist that is operating it. He further speculates that in an NDE the viewer becomes aware of and temporarily merges with this light, or rather, the light of a purer consciousness that is released from the physical and cognitive restraints of the body and brain.

While developing his analogy, Kripal additionally invokes Plato’s famous Allegory of the Cave. Very well-known to students of Religious Studies and Philosophy, in this allegory Plato invites us to imagine a cave in which prisoners are held in chains and unable to see what is happening behind them. They are thus compelled to watch a play of shadows on the cave wall that are created by their gaolers passing objects in front of a fire at the rear of the cave. The prisoners mistake the shadows they perceive for reality. Finally, a prisoner breaks free from the cave and experiences the open air and brilliant light of the sun. He realizes that what he had previously taken to be real was an illusion. Similarly, an NDE reveals that our materialistic view of reality and ourselves is false.

Plato’s allegory certainly helps to reinforce the point that Kripal wishes to make. But there’s more. As was already noted immediately above, reality as it is in itself, what Kant called the ‘noumenon’, is not what our senses present to us. All we have knowledge of is what Kant referred to as ‘phenomena’, objects as they appear to us after having first been mediated by those senses. Crucially for Kant, space and time are subjective structures, part of this phenomenal world. Our apprehension of time, of continuity, enables us to organise and fathom the inputs we receive from the noumenon.

Kant thought that the noumenal world was unknowable. Quite obviously, we can’t get outside of our brains to check that the cognitively processed data we are receiving accurately represents it. However, not everyone agrees about this. Buddhists, for example, would claim that meditation somehow enables us to access things as they truly are. It is also implicit in Kripal’s analogy that NDE’s might give us at least a partial glimpse of the noumenon. But what would a world without time and space be like? Is this something we can even begin to imagine?

If any kind of credence is to be assigned to certain statements made by Elizabeth Krohn, then with some help from the philosopher Boethius, the answer to the second question might just be ‘yes’. These are all to do with what she claimed happened to her apprehension of time in the Garden:

‘…I immediately understood that time is not linear. Things were happening in my field of vision…but they were all taking place at the same time, all at once.’ (pg.23)

‘…time in the Garden is perpetual. It is layered with events and sensations that occur all at once.’ (pg. 27)

Krohn is able to reconcile this experience of the ‘simultaneity of time in the Garden’ with her perception that she spent two weeks there by suggesting that time became linear for her again whenever she interacted with her spiritual companion, as this was the only way to enable her to grasp what she was learning. However, there is one big problem with all this: when taken in tandem with Krohn’s apparent precognitive powers, we end up in what Kripal later refers to as a ‘block universe’, one in which ‘the past, present and future exist all at once.’ The fact that the future therefore has, in this sense, already happened, is what permits Krohn to access it through her dreams, presumably by somehow flipping between linear and nonlinear apprehensions of time.

Krohn herself explains this ability by advancing her own theory about it, what she refers to as a ‘layer cake’ model of space and time, with the layers above the middle one (what we call ‘now’) representing the future, and those below it the past. She regards herself as somehow being able to slice through these layers to glimpse what are only ostensibly future events. Building on this suggestion, Kripal even speculates – with reference to a theory advanced by Eric Wargo – that time might be retrocausal and flow backwards from the future into the present, creating a situation where event A causes event B which in turn causes event A, effectively producing a mutually reinforcing loop effect that Krohn is tapping into. If all this sounds rather implausible, in the book itself Kripal provides an illustrative example that does make the theory at least seem worthy of consideration.

Fair enough. But Krohn’s description of the layer cake includes the telling sentence ‘I wish I had the ability to stop wherever I choose, but I don’t’, and this is where that aforementioned problem arises : there is no room for free-will in a ‘block’ or ‘layer cake’ universe, as everything is set in granite as it were. So the notion that significant events in our lives are ones that, as she also wishes to maintain, we have previously chosen while in a disincarnate state, makes no sense. And the same goes for any choices we make in the here and now. So it is unsurprising that Krohn is unable to stop wherever she wants to if free will turns out to be an illusion.

Furthermore, when it comes to ontology (the nature of reality) and soteriology (the nature of liberation), free will tends to be crucial for those who subscribe to a spiritual understanding of the universe. For example, given that there is a God who judges us (or in the case of NDE’s grants us a life review), if we were never able to make truly free decisions, if everything is already determined, then the very idea of meaningful judgement becomes nonsensical. Note that this would also have to apply to mass murderers. No matter how heinous their actions, any afterlife reckoning or punishment would be undeserved if they could not be held responsible for what they did, as moral responsibility is surely predicated on free-will. If we lack free-will, we cannot be held accountable for what we do.

Is there any way to reconcile these non-linear and linear conceptions of time in such a way that allows for the choices we make to be meaningful? One attempt at accommodation can be found in the writings of the early medieval philosopher Boethius (c. 480–524 AD), specifically in his famous theological treatise The Consolation of Philosophy.

Christian intellectuals like Boethius had been troubled by the implications of God being omniscient. For if God knows everything, then he knows what we are going to do before we do it, in which case, our actions cannot be free and we cannot be judged by God on the basis of them. God’s foreknowledge makes our ‘choices’ inevitable. Boethius tried to get around this problem by suggesting that God is somehow outside of time and space and views all our actions as if they were happening all at once. In which case, He does not possess advanced knowledge of what we do, and therefore our choices are freely made and we can be held accountable for them.

Unfortunately, this line of argument does not really help when it comes to Krohn’s self-understanding of what took place in the Garden, as is evident from her interactions with her spiritual companion. The source of the messages she receives from this companion about future events is quite obviously God, which means that He must know what is going to happen before it transpires. It would also, it is worth noting, be somewhat bizarre if He didn’t, as this would imply that God doesn’t know what day it is. Overall then, perhaps Krohn’s claims are only going to be believable for those who are willing to embrace paradoxes in relation to the nature of ultimate reality.

And this is not the only problem with the co-authors evaluation. At the end of the book, Kripal briefly refers to what is known as the ‘trickster effect’ in parapsychology. This is to do with the habit that supernatural phenomena exhibit of retreating under the glare of scientific scrutiny. When linked to what he calls the ‘sheep goat’ effect, according to which sympathetic ‘sheep’-type experimenters tend to uncover evidence of psi, while sceptics tend not to, the implication seems to be that this needs to be taken into account when those who claim to possess paranormal powers are invited to replicate those powers under laboratory conditions.

But does it? Perhaps all that is needed are better designed experiments with protocols that are rigidly adhered to. Someone who is a stickler for this approach is ‘the sheep who became a goat’, psychologist Susan Blackmore. Following many failures to experimentally confirm the reality of a range of parapsychological phenomena (telepathy, clairvoyance, astral projection, an alleged ability to perceive auras), Blackmore eventually became sceptical about even her own remarkable OBE that inspired her research.

As a student at Oxford she had a classic out-of-body experience in which she ‘flew’ out of her body, saw auras, and even became one with ‘the entire universe, expanding at the speed of light’. However, in later years it dawned on Blackmore that even spectacular experiences such as hers could be explained scientifically (in terms of what happens to the brain when it is in a state of shock or is overstimulated). For example, she thinks that the OBE is just a dramatic consequence our brain’s tendency to construct models of ourselves, which can include an ability to see ourselves from the outside under certain unusual conditions. For example, Blackmore reports that an out-of-body experience was repeatedly elicited in a tinnitus patient when his TPJ (Temporoparietal junction) was repeatedly stimulated by a neurosurgeon who was attempting to inhibit the intractable and intrusive sound that his patient was hearing****. This suggests that the TPJ could be the neural correlate for an OBE.

It is also of significance that when Blackmore tested people who claimed to be capable of astral projection to ‘visit’ her home in their disembodied state and identify numbers and common words she had taped to a wall in her kitchen by prior arrangement, none succeeded. Furthermore, tests on aura-seers requiring them to state whether someone was behind a screen or not (their bodies were not visible but their auras should have been poking out when they were stood close to the edge of it) the results obtained were not significantly different from those that were predicted by chance guessing.

Also worth a mention is the fact that Krohn is not unique. Dannion Brinkley is the author of a book called Saved by the Light, an account of an NDE he had after having been struck by lightning. Like Krohn, Brinkley also claimed that he developed psychic powers as a result of his experience, and that he was afforded glimpses of the future. As his book was published thirty years ago, we are now in a position to assess Brinkley’s gloomy prognostications concerning events that were meant to happen after 1994. Brinkley predicted that the world would be in ‘horrible turmoil by the end of the century’, that two horrendous earthquakes would take place in America ‘by the end of the century’, and that Armageddon would happen somewhere around the year 2004*****. With the benefit of hindsight, it is obvious that these predictions have turned out to be false.

Overall then, perhaps there is no ‘trickster effect’. That claimed paranormal abilities are not susceptible to testing in fact suggests – applying Ockham’s Razor – that they simply may not be genuine, however sincere the experimental subject may be in their belief that they possess them.

So where does this leave us? Has Krohn somehow been hexed by her brush with death and is now engaged – for unfathomable reasons – in some huge pathological project of self-deception involving alleged but actually nonexistent occult powers? Was her NDE nothing more than a shock-induced hallucination? Or should her testimony be taken in good faith as Kripal maintains?

Personally, this reviewer is inclined towards Kripal’s sympathetic treatment of it, as Krohn really does come across as someone who is likeable, articulate, sincere and genuine in the book. Indeed, one is reminded of the Harvard psychiatrist John Mack, who having interviewed people who stated that they had been abducted by aliens, risked his professional reputation when he concluded that they were neither mentally ill nor delusional and deserved to be better understood. Nevertheless, the explanatory gap between the findings of researchers like Blackmore (who also remains sceptical about the NDE phenomenon and thinks all the aspects of it are reducible to brain function), and some of the claims made by Krohn, is still undoubtedly considerable, and one is left wondering just what what it might to close it.

As for Kripal, his willingness to take NDE’s and other supernatural phenomena seriously should perhaps be understood as pushing back against the New Atheism of Dawkins, Hitchens et al. Notably, other academics working in the field of Philosophy and Religious Studies are doing the same. See, for example, Diana Pasulka’s research on UFOs and Non-Human Intelligences, and the growing interest in panpsychism among philosophers like Yujin Nagasawa and Philip Goff.

With this in mind, though this book is very much worth reading for students and teachers who are interested in the mind/body problem, evidence for the existence of the soul, and the divine attributes of God, there is one last reservation (actually more of an omission) that this reviewer had about it that is worth a mention. As a philosopher who specializes in religious thought, it is surprising that Kripal does not discuss the problem of evil in relation to the Near Death Experience. This is because, if NDEs are meaningful, and if life is a kind of classroom into which we choose to be reincarnated to have certain predetermined experiences, then what of those who are crushed or devastated by those experiences? What are the spiritual lessons that are being learned by – to select just two examples – the victims and perpetrators of Stalinist terror or the Holocaust? The presence of so much seemingly gratuitous natural evil also needs to be explained, and the suffering of animals in particular.

This is Philosophy of Religion 101, and so it is a shame that Kripal, who is such an imaginative lateral thinker, has yet to address these questions. As he is also a prolific author, someone with a lot to say (which is no bad thing in his case), it would be interesting to see how the varieties of supernatural experience might be reconciled with natural and moral evil. To the best of this reviewer’s knowledge, no-one writing in the field of the Near Death Experiences has attempted such a project, so a philosophical treatment from such an eminent author would certainly be welcome.

* As well as having written about people being ‘zapped’ by NDE’s, Kripal is the author of Mutants & Mystics: Science Fiction, Superhero Comics, and the Paranormal. So this epithet, which was bestowed upon him by Eric Wargo, is perhaps not undeserved.

**For Swinburne, if someone says x is present to them then we should assume that x is probably present unless there are good reasons to think otherwise, and people should be believed unless there are good reasons not to trust their testimony.

***Krohn is typical in this respect, having once said to Kripal that, “I am the screen to a movie when the visions occur.”

**** See Susan J. Blackmore Seeing Myself: What Out-Of-Body Experiences Tell Us About Life, Death and the Mind. London, Little Brown pg. 123-124.

***** Brinkley’s predictions are cited by Peter and Elizabeth Fenwick in their book The Truth in the Light: An Investigation of Over 300 Near Death Experiences. London, BCA pg. 167.