THE FOLLOWING BLOG ENTRY IS AIMED MAINLY AT STUDENTS AND TEACHERS OF A-LEVEL BUDDHISM, ESPECIALLY THOSE FOLLOWING THE EDEXCEL SYLLABUS ON TRIRATNA,THOUGH IT MAY ALSO BE OF INTEREST TO THOSE WHO ARE CURIOUS TO KNOW MORE ABOUT THE ASYLUM SEEKER ISSUE.

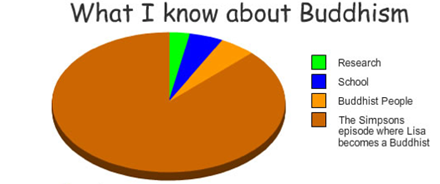

These days, the ‘pie’ depicted above is well past its sell-by date. Celebrity Buddhists like Lisa Simpson are no longer hard to find and learn from. The number of those who self-identify as Buddhist or take inspiration from the faith has steadily grown, a trend still driven by celebrity culture. The ranks of famous Buddhists now include Hollywood A-listers like Angelina Jolie, Brad Pitt, Keanu Reeves, Jennifer Aniston, Benedict Cumberbatch, Orlando Bloom, Sharon Stone, Robert Downey Jr. and Richard Gere (an animated version of him appears in ‘She of Little Faith‘, that aforementioned episode of The Simpsons), along with less well-known British figures, such as the fourth Dr Who Tom Baker, who refers to himself as ‘a sort of Buddhist’, Coronation Street’s Chris Gascoyne, and Bridgerton actress Claudia Jessie.

From the world of music we have Boy George, Tina Turner, David Bowie (who once contemplated becoming a Buddhist monk) and Leonard Cohen (who was actually ordained as a Zen monk in 1996), and turning to sport, the list includes Tiger Woods and former Italian footballers Roberto Baggio and Mario Balotelli.

The political landscape has also not been unaffected by Buddhism. For example, though officially Christian, former US President Bill Clinton took up the practice of Buddhist meditation after undergoing heart surgery, while the American Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks converted at the age of 92. Then there is the Tibetan Independence Movement, which aims to bring the Chinese occupation of the country to an end. Their campaign has received support from both Gere and Stone, with the latter attracting significant controversy after she suggested that the 2008 Sichuan earthquake may have been the result of “bad karma”, because the Chinese “are not being nice to the Dalai Lama, who is a good friend of mine.”

But then, as Donald Lopez Jr., professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan, has pointed out, ‘Tibetan Buddhism has been ‘in’ for some time. In the 1983 film The Return of the Jedi, the teddy-bear like creatures called Ewoks spoke high-speed Tibetan. In 1966, when the Beatles recorded ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, which begins “Turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream,” John Lennon asked the recording engineer to make his voice sound like “the Dalai Lama on a mountain top.”‘ Lopez Jr. also mentions that, ‘The I995 film Ace Ventura: When Nature Calls finds the protagonist living in a Tibetan monastery, doing penance for having failed to rescue a raccoon. He is dressed in the red robes and yellow hat of a Geluk monk, seeking to attain a state of “omnipresent supergalactic oneness.”‘ Lastly, FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper’s soliloquy in support of Tibet from the wonderfully surreal TV series Twin Peaks is also worth seeking out and sampling.

This kind of political activism is just one example of what is known as Engaged Buddhism, a movement that emerged in Asia in the 20th Century which attempts to apply Buddhist teachings to issues of social, economic, political and ecological significance. The phrase itself was actually coined by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh (1926 – 2022), who in response to the Vietnam War advocated a policy of non-violent resistance and the provision of aid to its victims. Since then, Engaged Buddhists have used boycotts, protest marches, letter-writing and other tactics to express their concerns about global problems. Overall, the movement belies the popular image that some have of Buddhist adherents as those who are detached from everyday life, being dedicated to purifying themselves of all worldly attachments in the quest to attain nirvana.

Tibetan and Engaged Buddhism aside, on the Dhamma Wiki list of celebrity Buddhists, one rather incongruous name stands out at the very top of it: Suella Braverman. What, we may feel entitled to ask, is she doing there? The purpose of this blog entry is to look at that question.

So why might someone be surprised to discover that Braverman is a Buddhist? First and foremost, this is because of comments she made when serving as Home Secretary. For example, shortly after being appointed to the role, she had this to say at a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party Conference in 2022:

“I would love to be having a front page of the Telegraph with a plane taking off to Rwanda. That’s my dream. That’s my obsession.”

Braverman was referring to her plan to outsource claims for UK asylum by refugees to the central African country, a proposal which was, and remains, extremely controversial, given Rwanda’s poor record on human rights.

At the 2022 Birmingham Conference, she also received a standing ovation for a speech in which she condemned left-wing lawyers and complained that there were “too many asylum seekers”. Shortly afterwards, she was at it again in the House of Commons, this time taking aim at “Guardian-reading, tofu-eating wokerati” whilst defending the government’s controversial Public Order Bill, legislation that was attempting to curtail disruptive public protests.

Not long afterwards, she doubled-down on her position. According to The Guardian, Braverman attended a meeting in her Fareham constituency in Hampshire, at which an elderly Holocaust survivor expressed concern that the then home secretary’s ‘description of migrants as an “invasion” was akin to rhetoric the Nazis used to justify murdering her family’. The paper reported that Braverman refused to apologise for her use of emotive language.

Fast-forward to the October 2023 Conference, and Braverman this time warned that the UK was facing a potential “hurricane” of migrants that were seeking to get here. As she put it, “[The public] know…that the future could bring millions more migrants to these shores, uncontrolled and unmanageable, unless the government they elect next year acts decisively to stop that happening”, adding that discrimination in one’s homeland for being gay or a woman were not sufficient grounds to qualify for international refugee protection.

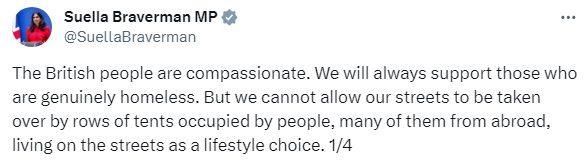

Just over a month later, Braverman then set her sights on the homeless by asserting that some rough sleepers were living in tents on the street as a “lifestyle choice”, and according to the Financial Times, vowed to create a civil offence which could lead to charities being fined if they hand out tents to homeless people.

In response, the shadow deputy prime minister, Angela Rayner, tweeted: ‘Rough sleeping is not a “lifestyle choice”. A toxic mix of rising rents and failure to end no-fault evictions is hitting vulnerable people.’ Homelessness charity Shelter also countered : ‘Let’s make it clear: living on the streets is not a “lifestyle choice” – it is a sign of failed government policy. No one should be punished for being homeless. Criminalising people for sleeping in tents, and making it an offence for charities to help them, is unacceptable.’

Prior to her making these statements, Paul Bickley, Head of Political Engagement at the Theos Think Tank, writing at a time when Braverman had just been appointed as Attorney General, did not think there was much for us to be concerned about. In an online article, he drew attention to the fact that Braverman was not a Buddhist novice but a mitra in the Triratna Buddhist movement. More on what that means shortly; but Bickley notes that being a mitra involves a commitment to observe five foundational Buddhist moral principles, one of which is: not harming other sentient beings, but actively practising kindness. Overall, Bickley appeared to want to suggest that, as none of these ethical precepts are troubling, we need not be concerned about someone who is committed to them. However, as we are already starting to see, it is not obvious that Braverman is cleaving to the first of these.

To reinforce this most important of all Buddhist precepts, Triratna beginners also practise metta-bhavana or ‘loving-kindness’ meditation. Starting with oneself, metta-bhavana involves gradually cultivating and then extending a feeling of kindness to others, including enemies, until, as one Triratna website explains, this feeling embraces ‘everyone around you…everyone in your neighbourhood; in your town, your country, and so on throughout the world. Have a sense of waves of loving-kindness spreading from your heart to everyone, to all beings everywhere.‘ Given, as has already been noted, that Braverman is not a beginner in Triratna, she must surely be familiar with this practice.

From this description, it is clear that loving-kindness or ‘metta’ in Buddhism is meant to be expressed impartially, and in a manner that is- in the case of migrancy – sensitive to the frequently traumatic experiences that motivate many to embark on what is itself a highly dangerous journey to reach the EU and UK, as the investigative journalist Sally Hayden has revealed through her meticulous chronicling of the personal stories of asylum seekers who have followed the Libya to Italy route. Presumably, metta should also be extended to “tofu eating wokerati”, “lefty lawyers”, and the homeless.

Similarly, compassion or karuna also plays a fundamental role in all forms of Buddhism and it, too, cannot be selective. Two Buddhist teachers, Christina Feldman and Chris Cullen, explain this concept as follows:

‘The Pali term for compassion is actually two words: anukampa karuna. Anukampa literally means “to tremble with.” This meaning points to the empathic dimension of compassion that resonates with and is touched by the suffering of another, as well as to the quivering of the heart in the face of suffering. The other and perhaps more familiar word, karuna, derives from the Sanskrit root meaning “to do or to make” or, in one version, “to turn outward.” Karuna captures the dimension of compassion that responds to the situation and seeks to alleviate suffering through action. There’s a dynamic relationship between these two aspects of compassion, because our engagement in the world must be attuned to the situation, which requires us to be present and listen deeply.’

Has Braverman ‘listened deeply’ to the plight of asylum-seekers and the homeless? The evidence suggests that she may have not.

Iannucci’s tweet obviously speaks for itself, though it should additionally be noted that Braverman’s faith actually has its origins in homelessness. Indeed, Buddhism’s roots are to be found in the sramanic movement of destitute spiritual dropouts from ancient Indian society. And even if Braverman was correct to distinguish between the genuinely homeless and those who may have deliberately chosen to live this way, the Buddhist approach would be to treat both categories of rough sleeper with compassion.

Similarly, when we turn to the asylum-seeker issue and its Rwandan ‘solution’, the same pattern emerges: a seeming failure to comprehend the reality of the situation in both instances.

Specifically, Braverman’s assertion that most asylum seekers are economic migrants, and her description of refugees landing at Kent as an “invasion” have both been called into question.

For example, Madeleine Sumption, the director of the Oxford Migration Observatory has been quoted as saying that – in comparison to other European countries – “the numbers coming in to the UK are relatively manageable”. This point is confirmed by the the OMO’s own figures for 2020/21, according to which Cyprus received 153 asylum applications for every 10,000 of its population, followed by Austria (42), Greece (27), Germany (just under 23), Belgium (22), and France (just under 18). In the case of the UK, the number of applicants was just 8 per 10,000.

According to figures released by the Home Office, for 2022 there were 13 asylum applications for every 10,000 people living in the UK. The report continues:

‘Across the EU27 there were 22 asylum applications for every 10,000 people. The UK was therefore below the average among EU countries for asylum applications per head of population, ranking 19th among EU27 countries plus the UK on this measure.‘

In 2022, five of the top nationalities entering by small boat in the first three months of the year were Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian and Eritrean. Many would have been fleeing from the Taliban, the authoritarian Shia theocracy in Iran, sectarian militias in Iraq, Bashar al-Assad’s autocratic regime or ISIS controlled territory when it comes to Syria, and in the case of Eritrea, a brutal and secretive dictatorship which has been likened to North Korea. Unsurprisingly, as the UK government itself has stated, for 2022 ‘just over three quarters (76%) of the initial decisions in 2022 were grants of refugee status, humanitarian protection or alternative forms of leave’, adding that, ‘of the nationalities that commonly claim asylum in the UK, Afghans, Eritreans and Syrians typically have very high grant rates at initial decision (98%, 98%, and 99%, respectively).’ These figures obviously belie the claim that most are economic migrants.

Towards the end of 2022, many more Albanians were also attempting the same journey. In her party conference speech of that year, Braverman had this to say about them:

“Today, the largest group of small boats migrants are from Albania – a safe country. Many of them claim to be trafficked as modern slaves. That’s despite them having paid thousands of pounds to come here, or having willingly taken a dangerous journey across the Channel.”

What is effectively a detailed rebuttal of these claims can be found on the website of the MCLU (Migrant and Refugee Children’s Legal Unit). Essentially, a country can be ‘safe’ in the sense that it is not war-torn. Nevertheless, slavery/trafficking can still be an issue, and it is one that the MCLU maintains that Albania is afflicted with, along with problems to do with ‘blood feuds, discrimination and violence against the LGBTQI community, stigma and discrimination against the ethnic Roma and Egyptian communities, and gang-related violence’, which the government there seem unwilling or unable to resolve. As for the cost of making the journey, it has been noted that ‘individuals become debt-bonded to work off the cost of their journey to the UK and [often] end up as victims of trafficking.’

It should also be borne in mind that other countries in the EU may not be safe for Albanians. This is because Albanian nationals have freedom of movement across the Schengen zone, and so asylum seekers fear that their persecutors may be able to pursue and locate them more easily within that zone.

As stated by the MCLU:

‘In the first half of 2022, 56% of all decisions made for Albanian applications for asylum resulted in a grant of protection or a grant of other leave. This figure does not take account of subsequent appeals, approximately half of which for Albanians over the last six years were successful [Home Office stats ref]. These figures indicate that the majority of those from Albania who claim asylum are genuinely in need of protection.’

A Home Office report for 2022 as a whole reveals that, ‘despite the overall grant rate for Albanians in 2022 being 49%, for Albanian adult men the grant rate was 11% and for Albanian women and children it was 87%’ whilst noting that, ‘the majority of recent Albanian small boat arrivals comprise of adult males’.

In summary, Braverman’s claim that Albania is a safe country remains suspect in the case of women and children, though it has more traction in relation to men who arrive by boat. Furthermore, by October 2023 the situation had changed. A UK government press release noted that small boat crossings by Albanian nationals had decreased by 90%, thanks to a growing UK-Albania partnership that, in part, aims to reduce organised immigration.

As for Braverman’s use of the term ‘invasion’, Philip Hubbard, professor of Urban Studies at King’s College London, has described the use of this militaristic metaphor as ‘dangerous’ because it creates the impression that those arriving by small boats are ‘a marauding force bent on aggression.’ He notes that such ‘dehumanising language’ had previously only been invoked by far-right groups like Britain First, and that Braverman’s ‘unapologetic use of such inflammatory language’ not only, ‘plays into the hands of such groups’ but also second-guesses ‘the motives of a population whose experiences, backgrounds and migration stories are complex and often traumatic.’

Given that Buddhists are meant to cultivate what is known as ‘Right View’ in following the path to enlightenment, a process that, in the words of Thich Nhat Hanh, entails an effort to ‘transform violence, fanaticism, and dogmatism in myself and in the world’, it is therefore difficult to fathom why, as a committed Buddhist, Braverman resorted to the deployment of such a provocative term.

Lastly, the policy of sending migrants to Rwanda is one that was spearheaded by a previous Home Secretary Priti Patel. It then received resolute support from Braverman, who insisted that “Rwanda has a track record of successfully resettling and integrating people who are refugees or asylum seekers”

However, as Rwandan political figure Victoire Ingabire Umuhoza has pointed out in an online article for Al-Jazeera, the country itself continues to inspire an exodus of refugees of its own nationals. As she puts it, ‘According to the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, in 2021 alone some 12,838 Rwandans fled the country and applied for asylum elsewhere.’ Additionally, Umuhoza draws attention to the fact that, ‘The Freedom House has been rating Rwanda as “not free” in its authoritative Freedom in the World reports for years. Respected international NGOs have been criticising the state of civil liberties and political rights in the country on a regular basis. Persecution of Rwandan opposition figures and perceived dissidents, in and outside Rwanda, have made international headlines many times before.’ She goes on to conclude that, ‘It does not make sense for Rwanda to welcome asylum seekers who are to be sent from the UK, while it has not addressed its own internal issues that are causing it to produce refugees of its own.’

For anyone curious to know more about the recent history of Rwanda and the track record of its current President Paul Kagame, this study is recommended:

Furthermore, according to a story in the Independent in October 2022, decisions made by Braverman led to overcrowding and outbreaks of scabies and diphtheria at a migrant processing centre near Manston in Kent. The newspaper claimed that she blocked the transfer of migrants to hotels in a bid to cut costs, but an effect of this was that numbers soared to triple the capacity of the centre, resulting in a flare-up of those diseases. Conditions at the overcrowded centre were subsequently described as ‘inhumane’ by the Refugee Council. Though the consequences of her decisions may not have been entirely foreseeable, they nevertheless seem difficult to reconcile with the Buddhist principle of ahimsa, of avoiding actions that intentionally harm sentient beings, especially as the article mentions that she was warned by officials that she risked breaking the law by housing migrants at Manston for a period of several weeks when the facility was only intended to hold people for 24 hours.

Most recently, in November 2023, Braverman was sacked from her post as Home Secretary. This was a consequence of an article she wrote for The Times in advance of a pro-Palestine protest rally on the 11th of that month, in which (apparently ignoring changes requested by Downing Street), she complained that police were showing bias in the way they dealt with demonstrations connected with the conflict in Gaza. In it, she stated that ‘Right-wing and nationalist protestors who engage in aggression are rightly met with a stern response, yet pro-Palestinian mobs displaying almost identical behaviour are largely ignored, even when clearly breaking the law?’

Former Metropolitan Police Chief Superintendent Dal Babu responded by claiming that her “unprecedented comments” had “emboldened far right groups to come out – who perhaps weren’t looking to come out – on this demonstration. So it’s going to make the job for the police much more difficult than it would have been”, while Conservative peer Baroness Warsi suggested that Braverman “had lit the touch paper and ignited community tensions”.

The Armistice Day commemoration at the Cenotaph was subsequently disrupted by significant clashes between far-right protesters and the police, thus confirming the fears of Babu and Warsi. According to The Guardian, officers themselves believe that Braverman’s allegation of bias was ‘a significant factor in “sustained” far-right attacks on members of the force.’ The event saw 145 protesters arrested and nine police officers injured; a large majority of those arrested were far-right counter-protesters, who were also accused of all the significant violent acts of the day.

Yet in comments afterwards, Braverman sought to equate the violent attacks mounted by far-right activists with what she claimed was antisemitic hate speech emanating from the far larger pro-Palestine protest.

In the light of all this, we may therefore be entitled to wonder why she is behaving in such a manner, given her Buddhist faith.

If she were Christian, a straightforward answer to this question could be supplied. It could be said that she was simply obeying her God-given conscience, which makes everything all right. But in response, no less a theologian than St. Thomas Aquinas would have rejected such an appeal. This is because, for Aquinas, a person’s conscience may well be ill-informed, and so they have a duty to better inform it. This is a point which should not have not been lost on Braverman, given that, as we shall shortly see, she gives precedence to duties over rights in her own political philosophy.

But in any event, for Buddhists, the God of classical theism does not exist, and the notion of conscience has no role to play in Buddhist ethics, for the simple reason that there is no persisting self (atta/atman) to possess one. In other words, as religious studies academic George D. Chryssides has stated, ‘To ask for the Buddhist view of conscience is rather like asking for the Church of England’s view on something like space travel.’

So we have to look elsewhere.

‘And what is wrong speech? Speech that’s false, divisive, harsh, or nonsensical. This is wrong speech.’ – The Buddha

Of the five foundational moral precepts of Buddhism (pañca-sila), the fourth (quoted directly above) is seen as the second most important. It refers to abstention from lying and other forms of wrong speech. When the relevant criteria – as encapsulated by Peter Harvey in his Introduction to Buddhist Ethics – are applied to Braverman, they reveal that she certainly appears guilty of ‘exaggeration’ with her talk of invasions and hurricanes of migrants, and culpable for speech that could readily be construed as ‘divisive’ and ‘harsh’, as we have already seen. ln the Buddhist scriptures, these would be condemned as examples of ‘wrong speech’. In particular, they go against the value that Buddhism ascribes to not harming others, seeking the truth, and seeing things ‘as they really are’. Given the stress that is placed within the Triratna movement on the observation of the five precepts, she can therefore hardly plead ignorance in this instance.

For those who would go as far as Babu and Baroness Warsi appear to in claiming that Braverman’s comments may have incited those on the far-right to act as they did on Armistice Day, again from the perspective of Right Speech, and in the words of Thich Nhat Hanh, they could be indicative of a failure ‘not to utter words that can cause division or discord’.

Moreover, all forms of Buddhism place an emphasis on paññā or prajñā, a term often translated as ‘wisdom’ or ‘intelligence’, but which according to Buddhist teacher Judy Lief, specifically refers to ‘a natural bubbling up of curiosity, doubt and inquisitiveness’. Through the cultivation of that propensity, an aspiring Buddhist would ultimately aim to acquire an intuitive and comprehensive understanding of the true nature of reality. Obviously, a prerequisite for the development of prajñā would therefore be a mind that is open, not full of itself.

Contrastingly, according to the Tibetan spiritual teacher Chogyam Trungpa, that aforementioned closed mind leads us to ‘adopt sets of categories which serve as handles, as ways of managing phenomena. The most fully developed products of this tendency are ideologies’ which ‘screen us from a perception of what is.’

When it comes to Braverman, it thus seems possible that she is in thrall to a politics that makes it difficult for her to see the wood for the trees. Or as ‘sort of Buddhist’ Tom Baker once put it….

The culprit here, as ever in Buddhism, is ego. The product of deep meditative insight, arguably one of the most fundamental discoveries made by the Buddha, is that absolutely everything is in a constant state of flux, including ourselves. So there is nothing that is stable and nothing to hang on to. Certainly, there is no place reserved for an unchanging soul or self. As the Buddhacarita, an early account of the Buddha’s life states, on the night of his enlightenment he perceived ‘the lack of self in all that is.’

Deep down, Buddhism maintains, we know this already. We know that we are nothing more than an ever-changing bundle of feelings, thoughts, reactions and fluctuating awareness residing in a body that itself is constantly aging and will one day expire. But the existential state of insecurity this knowledge creates in turn generates an ego, an illusion of selfhood. In seeking to maintain this illusion, we are willing to cling to any handhold, anything that provides a sense of security, and that includes systems of ideas, like nationalism, materialism, Christianity, even Buddhism. Right-wing politics would be just one more example. As Trungpa goes on to state, such ideologies ‘are used as tools to solidify our world and ourselves [as] we wish not to leave any room for threatening doubt, uncertainty or confusion.’

Does this mean that Buddhists should avoid politics? Absolutely not. For as we have already noted, many engage in politically activism with the aim of reducing suffering in the world. But the point is that the systems of belief Buddhists subscribe to should not be adhered to rigidly and inflexibly. They should be held lightly. The value of adopting such an attitude is conveyed very well by the Zen Buddhist teacher Brad Warner, who once said ‘I’m never sure that I’m right and someone else is wrong, for example. I might be right from one point of view, while the other person is right from another. Knowing this, and never believing I am entirely in the right, helps me to act more ethically.’

Why is this? Because certainty is an empathy killer.

Reflecting on her upbringing within the notorious Westboro Baptist Church, whose members adhere to an uncompromisingly literalistic view of scripture, from which arises their view that ‘God hates fags’, Megan Phelps-Roper had this to say when she eventually left that congregation:

‘Doubt causes us to hold a strong position a bit more loosely, such that an acknowledgement of ignorance or error doesn’t crush our sense of self or leave us totally unmoored if our position proves untenable. Certainty is the opposite: it hampers enquiry and hinders growth. It teaches us to ignore evidence that contradicts our ideas, and encourages us to defend our position at all costs, even as it reveals itself as indefensible. Certainty sees compromise as weak, hypocritical, evil, suppressing empathy and allowing us to justify inflicting horrible pain on others.’

When one thinks of the gratuitous harms inflicted on others by those who are utterly in thrall to some kind of perverse ideology (Hamas and Vladimir Putin serve as the most recent examples), then surely Warner and Phelps-Roper are correct when they suggest that we should be more willing to question even some of our most deeply held beliefs. So it is against this backdrop of Buddhist teaching that Suella Braverman’s politics needs to be evaluated. Has she displayed sufficient signs of epistemic humility? Of course, it is difficult to tell when she has not spoken publicly at length about her faith.

But there can be no excuses for any lack of reflection, as this is basic Buddhism. Even Lisa Simpson knows about anatta (the teaching that there is no permanent, unchanging soul or self), for as she points out to Todd Flanders (in the episode ‘Todd, Todd, Why Hast Thou Forsaken Me?’), the Buddha “avoids the pitfalls of ego”. Plus, and this is worth emphasising one last time, it’s not as if Braverman is a neophyte when it comes to her faith. When she became an MP, her oath of office was taken on the Dhammapada, a popular collection of the Buddha’s sayings in verse form.

Earlier we also learned that she is a mitra in the Triratna movement, so a few words are required about both the movement and her status in it. Formerly known as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO), Triratna was founded in 1967 by Dennis Lingwood (1925 – 2018), who was more commonly known by his Buddhist name: Sangharakshita. Although it started off in a basement in South London, his movement quickly expanded to other parts of the UK and beyond. Fifty years later, according to Robert Ellis (the author of The Thought of Sangharakshita : A Critical Assessment), Triratna now has centres in 65 cities around the world, 15 retreat centres, and around 1900 Order members. In particular, it has a strong representation in India, thanks to Sangharakshita’s involvement with the Dalit communities.

Prior to founding the FWBO, Sangharakshita had read Buddhist texts as a teenager, and lived in Sri Lanka and India during and after World War Two, culminating in him ordaining as a Theravada Buddhist monk, the oldest school of the faith. Subsequently, he also received instruction in Tibetan and Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism. The movement he started in England was an attempt to preserve the best elements from these traditions. Sangharakshita’s enterprise might thus be understood as an attempt to distinguish Buddhism’s core teachings from the cultural accretions that they eventually acquired, in order to then express them in a form that is suited to the modern world.

Having become somewhat disenchanted with monastic formalism, his desire to create a distinctively Western form of Buddhism (reflected in the ‘W’ of ‘FWBO’) included an emphasis on commitment but without the necessity of becoming a monk or nun. Ordination into Triratna is therefore ‘neither monastic, nor lay’. Instead it is based on commitment to, or ‘going for refuge’ in the ideal (Buddhahood/Enlightenment), Buddhist teachings (Dharma) and community (Sangha). Accordingly, the most serious members take vows, acquire a Buddhist name, observe ten precepts (ethical training rules), but do not wear robes. They are known as dharmacari or dharmacarini, depending on whether they are male or female.

Additionally, according to professor of Religion and Education Denise Cush, within the wider Triratna community, those who regularly participate in centre activities are considered to be ‘friends’ in the sense of being ‘just interested’. Friends can be of any faith or none, though some eventually choose to participate in a formal ceremony of affiliation, and thus become a mitra. Mitra is a Sanskrit term which also means ‘friend’, though in this instance it describes a person who regards themselves as Buddhist, makes an effort to live in accordance with five ethical precepts, and feels that the Triratna community is the appropriate one for them. Two of those five precepts have already been mentioned. The other three enjoin abstention from taking what is not given (i.e. stealing), sexual misconduct, and intoxicants that cloud the mind. So as a mitra, Braverman would typically be expected to keep these precepts as best she can. As for meditation, she would be expected to practise mindfulness of breathing and to cultivate metta-bhavana, which was described earlier.

So far, so good. But perhaps as a result of some of the concerns about Braverman’s adherence to Buddhist ethical teaching that this blog entry has highlighted, in May 2023, the Trustees of the London Buddhist Centre were moved to issue a statement distancing themselves from her. In it, they pointed out that she was not a dharmacarini, nor had she recently attended the Centre.

The statement continues…

‘Ms Braverman became a mitra in 2012. This denotes an initial personal commitment without any formal attendant responsibility. Some mitras maintain and deepen their involvement with Buddhist practice over time, seeking teaching and feedback, while others do not.

We have been asked if there is a process for ensuring ongoing accountability for mitras. For this level of involvement, there is currently no system for deciding if someone should remain a mitra after their initial declaration. Nor is there any attendance requirement or any other formal duty placed on a mitra. It simply indicates that at a certain moment someone has expressed an interest in absorbing more of the Buddhist teachings – whether they follow through, or not, is their decision.

Therefore neither The London Buddhist Centre nor Triratna has any responsibility for, or indeed, any influence with regard to actions carried out or statements issued by Ms Braverman in her role as an MP and Minister of the Government.‘

The Trustees also wished to correct a claim made in a Guardian article that Braverman attended the Centre ‘twice a month’. The Trustees omitted to mention that the article referred to Triratna as a ‘controversial religious sect’ that had been ‘rocked by claims of sexual misconduct, abuse and inappropriate behaviour’. This was a reference to an earlier story published by The Observer which alleged that Sangharakshita was a serial sexual abuser. In response, Sangharakshita has stated that he had engaged in a series of homosexual relationships between 1967 and 1988. He maintained that he believed these relationships to have been consensual, though as Robert Ellis states, ‘In general terms, he has apologised for any aspects of them that were not as consensual as he thought’.

Although it is beyond the scope of this blog entry to examine and evaluate these allegations, some points do need to be made about how all this could be perceived to reflect on Braverman.

First of all, the use of the term ‘sect’, like the word ‘cult’, might be construed as having negative associations. In the past, new religious movements and their leaders have attracted publicity for all the wrong reasons, and thus sometimes been characterised as dangerous ‘brainwashing cults’ or ‘sex cults’. Past examples have included The Family International (formerly known as The Children of God), NXIVIM, and the earliest incarnation of the Rajneesh Movement. But as Ellis points out, none of the five defining characteristics of a cult identified by Cult Information Centre can be clearly applied to Triratna. For the CIC, these are:

It uses psychological coercion to recruit, indoctrinate and retain its members.

It forms an elitist totalitarian society.

Its founder leader is self-appointed, dogmatic, messianic, not accountable and has charisma.

It believes the end justifies the means in order to solicit funds and recruit people.

Its wealth does not benefit its members or society.

Overall, the Guardian article appears to aim at guilt by association. But, given that Sangharakshita’s past behaviour has not been made a secret of by the movement, and that in any case, its present membership cannot all be deemed responsible for the failings of its founder, this approach seems highly unfair to Braverman.

But what the author might have done was to delve more deeply into Sangharakshita’s writings. Had they done so, they would have found some striking congruences between the latter’s politics and those of Braverman. The following is from an unpublished PhD thesis authored by the late Dr Sharon Smith (note that the mentions of ‘Subhuti’ reference the study depicted immediately above):

‘In the process to realise true individuality, Sangharakshita has been described by Subhuti (ibid: p. 215) as viewing many ideas that he sees as extant at the current time as inimical to the spiritual life. These he describes as “pseudo-liberalism”. Some examples he gives with their putative consequences are:

‘Egalitarianism destroys respect for teachers and leaders; the language of rights leads to a sense of deprivation, even among the most materially fortunate; …. gender politics obscure basic human facts and distracts from fundamental ethical issues; … populism leads to mistrust of high culture.

Subhuti then goes on to suggest that Sangharakshita regards ‘”political correctness”(for example, the censoring of language for any trace of what is deemed to be racism, sexism, ageism, etc.’) as even worse than pseudoliberalism (ibid: p. 215). In one of his aphorisms Sangharakshita (1998, p. 74)

states:

‘Political correctness’ is one of the most pernicious tendencies of our time – far more pernicious than pseudo-liberalism, of which it is probably the extreme form.’

Sangharakshita (1987) has also suggested in terms of debates around human rights issues that the focus should be on duties as opposed to rights, arguing that:

‘Duties consist in what is due from us to others, and are based upon giving, whereas rights consist in what is due from others to us, and are based (from the subjective point of view) upon grasping and getting. … the clamorous insistence upon our rights, upon what is legally, morally or even spiritually due from others to us, only strengthens greed, strengthens desire, strengthens selfishness, strengthens egotism (ibid p. 42-43).’

Now compare that with this extract from an article posted on Braverman’s own website:

‘In Brazil, there have been several cases of the use of torture by the police in the name of crime prevention. They justify this by putting a general right to live free from crime and intimidation above the rights of those who are tortured. To wipe out torture, the government would need to create robust, well-paid policing and judicial services to guarantee the same results. The government might argue that this money is better spent on new schools and medical clinics, protecting wider rights to freedom of education and health. These sort of value judgments, inherent in the practical application of human rights (whether we agree with them or not), undermine their “universality”.

But across most of the West, something else has happened to devalue human rights. A fatal misassumption plagues our whole approach to civil liberties: the predominance of the individual over the communal. The importance of the individual is seen as the defining axiom upon which we should base our policy and gauge its success. Emerging by reference to individual instincts and desires, rights and entitlements are paramount in our society, prevailing over considerations of how our choices affect others, over reference to past experience, or over the consequences for those born later on.’

‘…A fair, decent and reasonable society should question the dilution of our sense of duty, the demotion of our grasp of responsibility and our virtual abandonment of the spirit of civic obligation. What we do for others should matter more than the selfish assertion of personal rights and the lonely individualism to which it gives rise.’

Smith’s PhD thesis goes on to say this: ‘In rejecting the notion of rights, Sangharakshita is rather placing himself with some Buddhist scholars who consider the idea of human rights as incompatible with Buddhism on the grounds that to them it reinforces the ego and notions of an essential self.’

Having struggled to understand how, as a Buddhist, Braverman can justify her policy of wanting to ship migrants out to Rwanda, and some of her other political thinking (which we now learn includes a flirtation with the notion that torture may be morally justifiable), could it be that her views may be at least partly derived from Sangharakshita?

Of course, it is impossible to know for certain unless Braverman is more forthcoming about this herself.

In a not unsympathetic article for the online magazine Tricycle: Buddhist Review, Vishvapani Blomfeld, a member of the Triratna Buddhist Order, laments the fact that ‘it’s very hard to detect any Buddhist difference in the way she [Braverman] does politics’. But couldn’t it be said that Blomfeld does not go far enough in making this observation? For many Triratna outsiders, Braverman’s politics not only appear not to make a Buddhist difference’, but actually seem to contradict basic Buddhist ethical teachings.

Unfortunately, unlike their US counterparts, politicians in the UK tend to be more reticent about their personal faith. But in this instance, it is a pity that Braverman has said so little about it. If it is the case that her views on political correctness and human rights have been influenced by Sangharakshita, then it would be interesting to learn more about that, and how she thinks her ideas about the homeless and asylum seekers might also be reconciled with Buddhist ethics. The point she makes above about ‘the selfish assertion of personal rights’ does seem defensible when considered in the light of Buddhist teaching about the self or ‘atta’, and suggests that Buddhism could be potentially compatible with some form of Conservative politics. Nevertheless, such a politics would need to be more fully articulated. And that won’t happen unless this Celebrity Buddhist makes an effort to explain herself.